The mystery and the uncertainty that still hang over the roots of the the blues is a major factor that attracts me to the subject, almost at the same height as the joy that it gives me to listen to it. My constant amazement over the fact that a musical style which is at the end of the day a unique mixture of African and European tradition – born out of the brutal domination of one segment of the population by another one – has succeeded in fuelling the birth of the modern western music is no less of an important trigger in my perpetual look for the place and time of birth of the blues. The more I continue this search, the more I realise that there is no simple theoretical model that can be applied. One has to take into consideration a multitude of economical and social evolutions which took decades to develop. It is too easy to say that the blues has come from the Western African countries and goes back to the griots in Mali. It is a cliche that only covers a few aspects of it. I think that any realistic explanation has to start from the hypothesis that people and their culture evolve in a constant motion, full of internal interaction and in response to their environment. It would be too simple to see the blues as of an exclusive black origin. This false idea would seduce us in accepting what the commercial market tried to make us believe in the 20s and which ignores the black-white crossover effects that took place in those small communities where people with a radically different cultural and historical background met each other. They must certainly have been amazed at the way that they behaved, sung, spoke and danced. And even, if one part of the population brutally exploited the other one, this did not exclude that cultural sparks went over from one to the other.

We need to try to look for the roots of the blues without looking through the white prism that has been created and does no other thing than bias our view of the past. One of my favourite passages in Francis Davis’ ‘History of the Blues (1995) is where he states :

“At any given point in blues evolution whites have been the ones who have determined what the blues was supposed to mean. This has been true since the beginning. It’s possible that the whites named the blues (). Think it over : if you enslaved a race of people and put them to work like mules, might not be the music you hear them making for one another in their few unguarded moments sound to you like an expression of fear, discomfort or anxiety? The blues often was this, but it was just as often an attempt to forget all of this, dance music even at its most downhearted (…)”.

Much in the same line goes the approach followed by Alan Lomax, whom I propose to be our guide in what follows on one of the tracks back in time.

In his film “Appalachian Journey” (1991) he explores the roots of folk music in the community of the mountaineers in the Appalachian hills. With an exceptional combination of great expertise and tender passion for the subject, he describes how the music of the British colonists and the black community have been intertwined to create this unique combination of European and African sound that is at the roots of the folk music, black and white. It inspired the minstrelsy and later on the blues. As he states, the more we learn about those mountain communities where black and white lived together the more we see that they passed on to each other their musical favours. I quote his words :

Black influence was all through the whole of southern music. Southern culture was really a collaboration. Although the blacks were slaves they came from an area where the culture was at least equal that of their European masters and they brought tremendous sophistication.

They brought a different approach to religion. They brought a whole different way of looking at the relations between people, they had a different sexual system and of course the thing that appealed to everybody the most was their mastery of rhythm and of music and of a sense of life.

The intertwining is seen on different levels, in the performances, the dance styles, even in the instruments used. The banjo, a popular instrument in the folk bands of the hill country musicians, for example is based on the banjar, an African instrument to which one string has been added. Also, the dancing that developed was fuelled by the sophisticated poly-rhythms that came from Africa and that appealed to the complete body to express the emotions. The ballad of John Henry, perhaps one of the most famous ballads in American culture, was in its origin a song brought forth by the black workers that laid the rail road tracks in the mountain country : it was originally not a song that praised the work ethos of John Henry, competing with the steam hammer drive, but a clear allusion to the sexual strength and ardor of the character, a song which helped the rail road gangs overcome the times of hardship. The white folk communities heard the song and included it in their songbook, just as it became a steady component of the repertoire of the blues later on. The thrill that came upon me when hearing the majestic version brought by Furry Lewis is by the way the direct inspiration for setting up this very blog that you now visit.

This rough paint brush of the background to which blues originated in the late 19th, early 20th century serves the purpose of underlining once more, as I try to do all along on this blog, that the blues is a unique blend of music which is impossible to fully understand without digging into the social and historical context in which it arose.

Even though the blues stems from a particular social and economic configuration, it has yet a universal appeal which still makes it attractive now and across different cultures. It is amazing to hear the deep blues sound for instance on the newly released (10 May 2011) album of Hugh Laurie, better known as Dr House in the television series with the same name. What is it that makes it almost universally attractive? No doubt: it is the combination of both despair and joy, the way that melancholy gives a hand to pleasant feelings. Contrary to what is generally believed, blues is not only about pain, it is also the remedy against pain, as it is expressed in this song :

“Troubled in mind, I’m blue

But I won’t be blue always.

The wind gonna rise

And blow my blues away”.

It translates the weariness coming from a harsh social system, and yet it gives hope that one day better times will come.

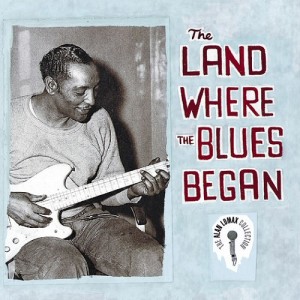

In his book “The land were the blues began” (1993), Alan Lomax develops a very interesting hypothesis on the genesis of this double layer, how blues can at the same time rouse pleasant, erotic feelings and yet evoke a sense of loneliness. From a model that he developed in 1959 (criticized however by many afterwards), called Cantometrics, he tried – on a world wide basis – to establish a relation between performance styles and the social and cultural system. His thesis claims that the length of the intervals in the musical scales is correlated to the rigidity of the social hierarchy. In Oriental cultures with a very strict caste-bound system, the length of the intervals tends to be much shorter than in societies (for instance African hunters and gathering societies) where there is a more egalitarian structure. African Pygmies’ songs for instance are characterized by big leaps in the musical scales that are thus meant to express freedom. The African imported slaves in the American colony brought with them those long intervals, but these were combined with flattened, narrowed intervals (he calls this narrowing of intervals : blueing of intervals). I quote : “The many big leaps give a sense of freedom (a permissive sex code, a feeling of social equality within the community) (…), but the narrowing or blueing of the intervals tinge them with irony and sadness, as the impact of the caste-class system negates these positive feelings“. Rephrased in a simplified way : the long intervals expressing freedom and joy hit on the harsh walls of the caste-system. Blues stemmed from the “painful encounter of the black community with the caste-and-class system of the Post-Reconstruction period” (EB : Reconstruction period refers to the post Civil War period during which the Southern states tried to overcome the disastrous impact of the Civil War).

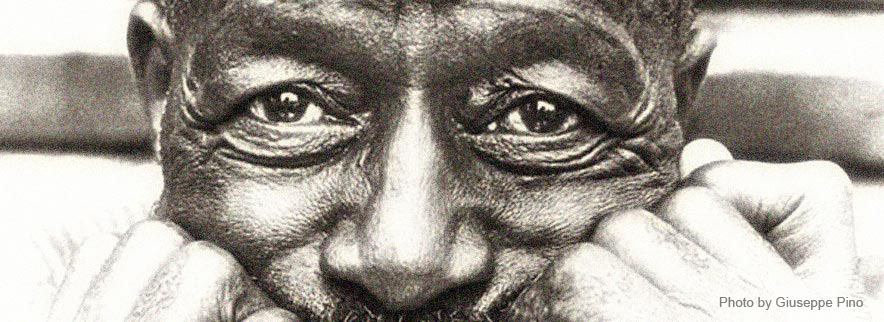

Lomax praises greatly as an example of this combination the songs of one of the great original country blues originators, Freddy McDowell, whose music takes “us into the region of heart cries, or at times of tender ecstasy“. His music testifies of the tragedy of his people and yet it is also the dancing beat that rocked the barrel house all night long.

Freddy McDowell is on the same level as Son House and Muddy Waters, but is considered, musically speaking, as their grandfather. His musical roots lie in the North Mississippi Hill Country Blues, in the region around Como in the Panola County which borders the Mississippi Delta on the east side. It is some 70 km north east of Clarksdale. Though there is flatland, and there are cotton fields, the region is not as fertile as the Mississippi Delta enclosed between the Mississippi and the Yazoo river. Its landscape can best be described as a “thick blanket roughly shaken across an unmade bed” .

Why do I go into this detail? Freddy McDowell can be seen as making the bridge between the sound that he picked up on the one hand from the local guitarists and the grooves he heard in the juke joints of the North Mississippi Hills and on the other hand from the raw blues Delta blues (http://www.msbluestrail.org). The style of the North Mississippi Hills is much closer to the African style, but he mingled it with the music that he picked up during his years in the Delta plain.

We touch here, in my opinion, and if my understanding from the literature on the matter is correct, on an essential branch of the pedigree of the blues, a branch of which the roots lead us into those Mississippi Hills where we come across names as Sid Hemphill, Lucius Smith, Othar Turner and Napoleon Strickland. Here we find a one time mixture and merging of West African musical styles with European traditions up to a point that it is sometimes hard to make up if a song has a black or a white origin. The most notorious figure is without doubt Sid Hemphill, a band leader, composer and a multi-instrumentalist making his own instruments. The music that he played was a rare archaic combination involving drums (bass and snare drum), fife, fiddle, banjo, mandolin and other local instruments as for instance quills. I almost forget to mention that he was blind ! Anyhow, he was part of a band of musicians who played at local parties and picnics, both black and white. It is important to stress here, that contrary to the later hobo figure of the Delta blues musician, the country hill musicians performed not only in a band, but this band was strongly integrated in the local community. It was not a wandering group of musicians, they worked as tenants or share croppers and were hired to bring music to the local public events. Sid Hemphill was himself the patriarch of a large musical family : he passed on his musical talent to his daughters and granddaughters who would later make a name for themselves (even on the international scene).

The guitar nor the mouth harp play a central role in this music, they would only became later the key instruments of the delta blues performer. Banjo and fiddle are at the heart of their music, and not to be forgotten : the fife and drums. Black fife and drums are an aspect of the pre-blues period that is often ignored but that had received more and more attention since Lomax in 1942 has recorded a drum and fife band for the first time. Ever since, more and more drum and fife bands have been discovered and their importance in the emergence of the American folk music has been recognized (http://www.folkstreams.net). This should indeed not be too surprising if one takes into account the findings that from the early days of slavery Africans were hired into the militia of the colonists, and that they were allowed/invited to form marching bands of drum and fife players in those colonial militia. They were formed to the image and example of the white militia orchestras, both in the Northern counties and the Southern counties, and constituted themselves sometimes as band for dances. After the Civil War, the northern bands became mostly white, and in the Southern regions, the bands were almost exclusively of African American composition. They were to be the cradle of the later minstrelsy shows, the white parody on the black (musical) life.

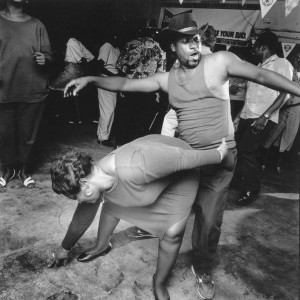

The musical events and dance parties were, fully in line with the African tradition a communal happening during which it was often hard to draw the line between the performers and their ‘audience’. Vocals, instrumentals and bodies all moved together, in a mutual interplay, to bring about a common expression of joy, often ending in pure ecstasy. However, what was fundamentally non African, was that the dancing couples were mixed. On the basis of a world wide survey, Lomax observes that the face-to-face dancing of couples is rather typical for the European western world (with a nuclear family type) and for some northern African regions. Generally, in African tribes men and women danced separately; the groups could be mixed, but the couples seldom or never were. Men and women joining in couples to dance was thus clearly a style that has been imported from the European tradition, but then again, it was not the stiff, Calvinistic way of dancing that was adopted. The African culture brought with it a whole new vision on the role that sex played. In the Victorian tradition, the sexual aspect of the social interaction was hidden, while the slaves brought with them a culture in which sex was non-disclosed. This mixture of African and European tradition brought about very sensual dance styles of which the essence was about couples exploring each other in an intimate bodily contact. One of the products of this evolution is the blues ‘slow drag’ which seems to have been an innovation going back to the end of the 19th, beginning of the 20th century. It is striking how Lomax admits in his later publications that his father and himself had observed the open way in which the black communities in America dealt with sex, which was the subject also of many tales. However, by fear of not having their work published they did not dare making any mention of it in their reports !

Thus, in the hills of the Mississippi, a culture had formed itself which had the clear marks of both the African and European tradition. Local string bands, and drum and fife bands were the popular way of entertainment for the week ends. Dance was music and music was dance. And for Africans, music was part of their daily life. It was a form of speech. Moreover, when the bands played, the whole community was participating. This entertainment stood far from the European model in which a band played before an audience which utmost participation consisted of applauding after each number.

Meanwhile, in the delta plain the rich soil was bit by bit conquered on the water of the Mississippi and the Yazoo, and work prospects were attracting people from the hills. There was plenty of work on the levees, in the construction of the rail roads and in the exploitation of the plantations. Over time, we see a shift from the band music to the individual musician. Banjo, fiddle, fife and drums are being replaced by the guitar and by the mouth harp. Lomax keenly observes how some musicians had developed a highly complex way of guitar playing (guitar picking) where they could play at the same time the melody and the rhythm. The left and the right hand had learned how to act independently and yet in harmony with each other: the previous band music was slowly replaced by the one person band performing only on the guitar. “() Black country guitar pickers taught their instruments to sing the blues and, at the same time, to serve as one-piece dance orchestras, evoking the multiple patterns of the old-time string band by beating, picking, plucking, hammering, pushing and sliding. This new six-string virtuosity so fascinated the black working class that a lone bluesman with a guitar was enough for a dance and a party. His music kept everybody happily on the dance floor and his lyrics, sung and picked, told every body’s story.” (Land where the blues began, p. 352). In the same way as the string bands did, the lone blues player interacted with his public to surf on the waves of the mood that was hanging in the juke joint or on the picnic.

The social background of the blues man in the delta was however different from the one against which the bands operated in the hills. During slavery, there existed a closely knit social system in which plantations made up the social entity. Surely, tenancy and sharecropping also kept the blacks shackled to the ground and his owner through debts, however, the social disintegration had set in, and would be further reinforced by the start of the Great Migration to the northern industrial cities starting as of 1910. It happened on the global social level, and it happened on the level of the individual families. The families were large, but it was often impossible to say to which parents the children belonged. The crowing of the red rooster was a very functional way of alerting a woman that her husband was on his way back home to give time to her lover to skip out as the backdoor man. Disrupted families were an essential characteristic of the social tissue. Just as children were in a very early life time left to the care of one parent, or even a grand parent, it was not uncommon that a woman would integrate into her family the children who had been left behind by other families.You only need to go through the biographies of some early blues artists to see how often they were left on their own at an age not much above 9 or 10. Lomax even sees a connection between the blues style and the family background of the artist : early orphanage was often the source of a blues style filled with more sorrow than the one brought by others who did not experience it. Muddy Waters’ more gentle style is explained by the fact that he had grown up in a rather stable family structure.

Anyhow, music offered a socially acceptable way to shake of the shackles of the tenancy and the sharecropping, but the fate was then very often the life of a wandering musician. But this life was also rewarding in more than one respect. It brought freedom, and what was more important : it brought cash in the pockets. Singing the blues was pecuniary much more interesting than the uncertainties of the reward system of tenant or sharecropper. Music was by the way, the only way that blacks were allowed to climb up in the social hierarchy.

Once a blues artists, one was also considered as uprooted, not bound by the social codes. Blues was the devil’s music and was totally in-congruent with the religious norms of the community. Gospel was the music of the believer; blues was the music of the devil. Some artists, as for instance Son House, have constantly struggled with this dichotomy.

But there was still another rewarding aspect about being a lone blues performer. He attracted women. Indeed, they knew that this devilish man had money in his pockets, ready to be spent. “Blues men could afford to dress better, drink more, gamble more, have more good-looking women” (Lomax, p. 359). In an interview, one of the early blues artists, Eugene Powells declares: “If I seed some woman I liked, I’d come whopping the blues down hard” (Lomax, p. 373). The sixties were the period of sex, drugs and rock & roll. But it is not hard to imagine the period of the early (country) blues artists as the period of sex, booze and blues. When a blues man sang about the pain that was inflicted upon him by his woman who had left him, it is self speaking that when a woman leaves a man, this other man most often breaks through the contours of the nuclear family. It takes two to tango. Sexual conflicts may sometimes have stood symbolically for the conflict between black and white, as such they were also a major component of the social behaviour. It were the “hard decades (of) the careless love when the women, like dollars, rolled from hand to hand” (Lomax, p. 381). It was not a big surprise for men to find “another mule kicking in their stall”, as Sam Chatmon once depicted it in a very plastic way.

In this post I have tried to accompany you back in time on a journey from the north Mississippi Hills to the Mississippi Delta. In blues surveys a distinction of style is often drawn between the north Mississippi hill country blues style and the delta blues style and some will underline this very strongly. However, it would be in contradiction to the point that I have tried to make all along this post to not see both as aspects of the genesis of a truly unique event in the modern music history. After all, the hills and the delta were not more than 100 km apart from each other, and the people that descended to the plains left a family behind in the hills whom they surely visited on a more or regular basis. It would be short sighted to ignore the mutual influence that both styles have had on each other. In their very essence, they both ‘blued’ the notes : notes that in the wake of the mixture of African and European traditions express at the same time pain, sorrow and sensual joy and happiness.