Those familiar with my blog will already have noticed my appetite for titles which tend to be provocative and in which I try to link seemingly unrelated events or circumstances. This post is not different from the previous, but I hope that when you will have stopped reading this post the full meaning of the title will be clear. My first idea was to call it: “How the blues helped to kill the Black Swan“. It would have been as provocative and as apt as the finally chosen one, as you will understand in a few minutes reading time.

What is a Black Swan Event?

The theory of the Black Swan was coined in 2007 by Nassim Taleb to describe an event that is (i) not predicted, (ii) has a very significant impact and (iii) can be rationalized after the event, making it thus more predictable. He considers that almost all major events in the political, scientific and artistic realm can be considered as black swans. The rise of the internet is but a very striking example. The financial crisis in 2008 was another one. It was a very major event with huge consequences that apparently came unexpected, but that in an ex-post analysis was clearly explainable. The 9/11 event is another one that is often quoted as an example.

What is the Black Swan Label?

The Black Swan label was the first major (there had been a smaller one in 1919, called Broom Records), wholly black owned, record label that issued records. Its short existence between 1921 and 1923 has been put in the shade by the later creation in 1960 of the Motown label which is popularly known as the first label owned by an African American. This popular knowledge however is wrong: all credits have to go to the Black Swan Label.

But was the Black Swan Label in its emergence and sudden fall also a Black Swan Event? I think it was, at least to a certain degree. I’ll try to convince you in what follows.

But let me first pinpoint the historical context of the creation of the Black Swan record label; this will help to understand why the Black Swan became that rapidly a dead duck.

When the label saw the light in 1921, music was at its heydays after the World War I. Since the invention of the phonograph in 1877 the record industry already had undergone a serious evolution. From its earliest destiny as a dictaphone, as conceived by Edison, the phonograph/gramophone had turned out to be a huge success in the form of automatic phonographs around the turn of the century as part of a larger entertainment industry. It was open for the (urban) public and was bringing dominantly popular music for who-ever inserted a coin in the ‘machine’ and picked up the “ear tubes” (yes, the first phonographs were in fact primitive juke boxes that played their music through earphones!).

It was only afterwards that the Victor Talking Machine Corporation brought the gramophone out of the public scene in phonograph parlours to a comfortable and private place next to the old Victorian smelling piano in the living room. The explicit goal of Victor was to give the gramophone an aura of respectability, at the same level as the piano in the houses of the middle- and upper classes. It wanted to spread again what used to be known as the music for the classes, not for the masses (William Kenny, 1999, p.50). The price level of the gramophones was set accordingly. The gramophone cabinet was explicitly marketed as furniture that fitted in the home of the wealthy class. It was no surprise in this context that some companies sold gramophones cabinets in the form of luxury furniture ornamented with Greek looking columns made of expansive wooden material.When the patent for the flat, horizontal disc technology was still held by Victor and Columbia, both companies dominated and split the market, together with a distant third party, Edison, which was limited to continue with his cylinder-technology that had been the key component of the previous, by gone hype of the automatic phonographs (“coin-ops”). When Columbia and Victor could no longer rely on their exclusive patent in the second half of the 1910’s, the record market boosted. The number of record companies went sky-high. Perhaps, the musical explosion was also an explosion of joy after the sorrows of the World War. In any case, music was promoted more or less as a national duty: music was seen as being morally uplifting. Pianos were even exempted from the wartime luxury tax as a social necessity! (Suisman, 2004, 1296).

Phonograph manufacturers directed their attention also to migrant populations bringing them something to remember from their home land. They appealed to their collective memory as a social group. Chez and Chinese songs were no exception.

Ragtime and other African-American rooted music were an essential component of the musical scene, as were the ‘coon’ songs and the minstrelsy, still rooted in the 19th century, bringing forth and confirming the stereotype of the lazy and clumsy Negro. This way the white dominance and its supposedly racial supremacy were confirmed again and again.

African-American music was however not considered suitable for the record industry. It was regarded upon as of a lower quality. George W. Johnson had made it to the record studio as the first African-American at the turn of the century and even had tremendous success in the then still cylinder based record industry. However, this exception in fact confirmed the rule, since his repertoire was in fact no more than a translation of the dominating coon song style. His successes (“Whistling Coon”, “Laughing Song” – you can hear them here) did no more than illustrate the ruling African-American music paradigm based on a caricature of the Negroes.

The World War changed the spirits of the African-American population fundamentally. They had made the acquaintance in Europe of a wholly different culture in which race was a far less dominant element. When they returned home from the trenches, their expectations were high, but disappointment came very swift. The tension between reality and expectations no doubt contributed to the growing awareness of the black activist. The Jim Crow laws were no longer taken as granted; moreover, the Great Migration to the North put a better life at the horizon, with a higher income and more access to the luxury commodities of the modern society. This ‘New Negro’ expected to take part in the benefits of the fight for democracy he had been involved in on the European battlefield.

But this expectation was only met with severe white hostility and violent race riots were the result at the end of the 1910’s.

In Harlem, New York, previously a neighbourhood for the well to do white class, but afterwards invaded by migrants from Europe, and after the World War I gradually occupied by the black migrants from the South, the rising expectation had also given birth to the so called Harlem Renaissance. This New Negro Movement rejected every form of stereotype based on the blackface and minstrel tradition and underlined the strong black cultural values in literature, theatre and music.

In this historical context, W.C. Handy (the self-proclaimed father of the blues) and a certain Harry Herbert Pace met in 1907 (some sources quote 1912). Though their musical preferences were divergent (Handy went for the more boisterous street music, while Pace was more in favour of the sweet, sentimental song), the teaming of the two men came as natural. According to the words of Handy: “It was natural, if not inevitable, that he and I should gravitate together. We spoke the same language” (quoted in: Black Swan Blues, Paul Slade).

Harry Herbert Pace, a light skinned black, was born in 1884 in Georgia. His father died when he was still a baby and he was raised by his mother only. He was an extremely bright kid who made it with tremendous success to the Atlanta University. He took up several jobs in the printing, banking and the insurance sector. Next to small-scale service activities as dressmaking or storekeepers, the banking and the insurance sector where the only ones where blacks could take an important position. They were excluded from other sectors.

As a business man who also made name as a re-builder of failing enterprises, Harry Pace was however also a skilful songwriter, and the combination of the song writing talent of both Pace and Handy and the business skills of Pace proved to be very fertile.

They founded the music publishing company “Pace & Handy Music Company”, and scored their first massive sheet music hit in 1914 with “St Louis Blues”. Pace moved up to New York into Harlem to manage the Pace and Handy Sheet music business.

Handy and Pace marketed quite some music with success, but they observed that the white companies refused to have it recorded by black artists who were systematically confronted with a turned thumb. The music was recorded by white musicians, without much respect for the authenticity of the material. In the words of Pace, they run up “against a colour line that was very severe”.

The black population was totally marginalized, also in the entertainment business, where they could only hope to show their talent in the role of a coon in a comedy. Even as employees in the business, they were almost totally absent, let alone that they could decide on the musical output for the market. It was not uncommon that the argument was used that the black voice did not record very well! (Slade, 2009).

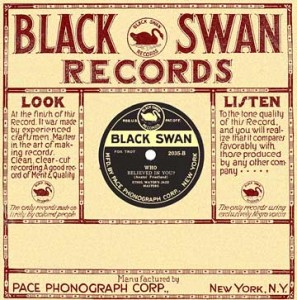

Out of this frustration, Pace founded in 1921 the Black Swan Records as the record division of the Pace Phonograph Corporation Inc. The inspiration for the name came from the African American opera singer Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield (1809-1976) who was known as the Black Swan. The company was set up as a small starter with a modest capital, but with a huge ambition: serve the black stockholders, employees, singers and musicians. It was the expression of Pace’s ideal to give a concrete form to the black people’s aspiration for control on their material environment. By showing what black people were capable of producing on the cultural level he wanted to break down the social barriers in the segregated society. He wanted to shape the public opinion in order to obtain a meaningful change of the social position of the black population. Control of public opinion was, according to him, a mighty tool to foster social change, even if the roots of the racial hierarchy were of an economic nature as he very well understood.

His way in the black record sector had been paved a year before by Perry Bradford, a pianist in minstrel shows, who had – after considerable effort and a few pair of worn out shoes – succeeded in convincing Okeh records to market a blues song by Mamie Smith. Her ‘Crazy Blues’, backed up by a whole black band (her ‘Jazz Hounds’) became an unexpected but huge success. Okeh had gambled and had won. It had in fact little other choice than to gamble since the big companies as Victor, Columbia and Edison had contracted the musicians with such lucrative contracts that little other talent was left over to be fished in the musical lake.

Anyhow, the success must have convinced Harry Pace even more to take a step further and put in place a record company that was wholly black owned and controlled, and which could decide itself on what products to market. With this initiative he reflected the middle-class black ambitions which tried to demolish the racial barriers by introducing the black population in the business sector. His company was an illustration of the emerging Black Nationalism that began to sweep the U.S. in the early 1920’s.

It is no surprise when I say that his initiative was not really welcomed by the white segment of the (business) population. This is an understatement for the observation that he and his company were the subject of slander, defamation, economic boycott and even of attempts of violent attacks (once a bomb was found in a package that was to be shipped to a record pressing plant). Without any doubt, the weight of the company board has helped to cope with the hostile attacks : the board was composed of important black public figures from different professions, of whom the most important was W.E.B. Du Bois, an academic and former tutor of Pace at the Atlanta University, and a key person in the civil rights movement for black emancipation. His prestige as an intellectual leader certainly helped the Black Swan Label to offer a counterweight to the aversive attempts of the white population to marginalize and even exclude his company from the market.

The artistic start of the company was modest in the spring of 1921 with the recording of vocal work in the vaudeville style. It could hardly be called blues, and it certainly didn’t appeal to the taste of the masses of the African-American people. If no other talent was found, the company would have had a very short live indeed. Luckily, Fletcher Henderson, the house pianist, band leader and also the recording manager of Black Swan struck a vein of gold when he heard Ethel Waters (some sources say that Pace discovered her), a vaudeville singer and dancer, performing in a Harlem cabaret (she already had her recording debut on Cardinal Records earlier that year). She recorded ‘Oh Daddy’ and ‘Down Home Blues’ in the summer of 1921, which made an enormous success. Estimates are that a couple of hundred thousand (!) copies were sold in the first months. Perhaps this figure is somewhat exaggerated, but in any case Ethel Waters helped to get The Black Swan out of the red figures.

The Pace Phonograph Corporation was definitely launched. Following the example that the Victor Talking Machine Corporation had set in the 1910’s using important advertisements to promote their products, so did Harry Pace made an intensive use of advertisements in newspapers to establish the link between culture, race and the consumption of his products. The Black Swan label was portrayed as the sole defender of the black artist’s musical talent. Systematically, his products were promoted as the only records using exclusively Negro voices and musicians. As a matter of fact, not only the musicians were black, the whole crew was black, up to the girls putting the stamps on the envelopes, and Pace made this constantly a crucial element of his advertising. Likewise he highlighted the quality of his recording; the sleeves of his records should already breathe the attention that was paid to the recording in the studio, up till the pressing of the record.

No efforts were spared to get the largest possible distribution of the records notwithstanding the obstructive actions from his white competitors. The records were sold everywhere possible where the black consumers could buy them: railway stations, street corners, all types of black shops,… Even if the buyer didn’t own a gramophone player, it should be seen as an act of black activism to own a record.

Harry Pace took a further step, building on the success of Ehtel Waters : organising a nationwide tour that would bring the artist and her band through 53 cities in 21 different states. Where they came, Ethel Waters and her Jazz Masters stole the show, and the critics were positive all over. She managed to have a public that was both black and white. Things were however quite different when she headed for the Southern states. The perspective of the white hostility and aggression was already enough for some band members to abandon the idea all together; however, they were quickly replaced and in a large group, offering more protection than a small one, they set out for the trip to the South. It is hard for us to fully grasp how courageous this step was at the time. When you think of it that Louis Armstrong when touring in his bus through the Southern states in the sixties, even had to use what nature offered to do a pee, instead of using the toilet facilities in the eating stops along the road, we can try to comprehend what it meant to start touring in the beginning of the 20s as a black band in the South. It was rewarded with success though, even with the white audience. The shows however needed to be organised on a strictly segregated basis: a show for the white audience, and a separate show for the black audience. With only one exception, there were no racially mixed performances. To illustrate the hostility that the band met in same places, the story is well known and reported of the young boy that had just been lynched by a mob and was thrown in the hall of the concert hall where the band was to perform. This was all the more painful as the youngster was the son of a woman living next door where Ethel Waters stayed overnight!

It is kind of curious, or should we call it, heart breaking that the black band had success on stage with the white audience, but that as soon as the black artist was on the street he was the target of hatred, insult and aggression!

When Waters and her ‘Troubadours’ turned back to New York in July 1922, Black Swan Records was financially in top shape. Enthusiasm was all over the place.

At the same time, it was however also the start of the decline, which was definitive in December 1923 when Black Swan declared bankruptcy.

There is quite some literature on the reasons why the company had to close its doors. Davis and De Loo wrote a paper in 2002 analysing the bankruptcy from a micro-economic and accountant’s point of view, highlighting the heavy overhead costs and some poor management decisions. Bad investment actions would have contributed to the quick decline. When Ethel Waters returned from her glorious tour, the profits that it had generated were all too quickly spent on heavy investing in a new building and the acquisition of its own pressing plants to keep up with the ever growing demand which surpassed the production capacity. Certainly, we can understand Pace’s decision to buy his own plants for pressing his records in order not to rely on the infrastructure that was hired from Paramount (oh irony!). Davis and de Loo argue that it would have been a better decision to temporarily allow for a gap between offer and demand than to invest the profits thus leaving few margins to cope with possible misfortunes. And the misfortune was not far off with the increasing competition of the radio. After all, let us not forget that Black Swan Records remained a very small company compared to the bigger companies as Paramount and Columbia. When the record industry had to cut its prices to face the rivalry of the radio, it severely cut in the profit margins. This came at a very bad time for the Pace Phonograph Company.

But the introduction and success of the radio medium cannot explain in itself the decline of the company. Surely, it is always easy to find explanations ex-post, but there is sufficient ground to argue that the company was born under a bad sign, and that its very own business and cultural objectives contributed to its own decline. I know that it is a very rough simplification, but I’m not very far off when I state that Black Swan’s foundation on the racial division of the market was in itself a structural element that lead to its decline. Can a music company justify its ‘raison d’être’ on the sole element of the colour of the skin of its consumer community? I would say: hardly.

When we have a closer look at Pace’s vision, we can already detect some potential for conflict that was to undermine the company. The ultimate goal of Pace was the social and economic uplifting of the black population through the promotion of the music of the black. Which music? Pace’s background had prepared him more for what is called middlebrow or highbrow music, not the popular music, the down to earth blues and jazz. Already from the very start, his vision on what kind of music that should be promoted for the uplifting of the black was clear when he discussed with his production manager, Henderson, the type of music that Ethel Waters was to wax on her first record. Pace was more in favour of the ‘cultural’ kind of work, whilst Henderson was more in favour of the popular type. It was finally decided that it would be the popular music, and ‘Down Home Blues’ would be the first big success of the company and also its most ‘bluesy’ song. Ethel Waters’ voice however was probably as far as Pace wanted to go: she presented the midway between his musical vision and what he expected that the market would buy. Slade (2009) confirms the often told story that Bessie Smith was rejected in an audition at Black Swan: not only did Pace consider her voice as too rough and crude; Pace also disliked Bessie Smith’s behaviour (especially when she asked to interrupt a song because she wanted to spit on the floor). Bessie Smith embodied for Pace everything that he disliked about the blues. His vision on blues was clearly not this that was living amongst the majority of the black population. Even the company’s name and reference to a vocal, classical star said enough about the kind of music that Handy preferred.

Here lies a crucial point that helps to understand why it went wrong. On the one hand, Pace tried to foster the cultural and social uplifting of the blacks by associating it with high class music, on the other hand: its company survival was largely, if not exclusively dependent upon the down to earth blues and jazz products. However, this was also precisely the market segment where he met the most severe competition. Let’s say that he had created a playground for itself but that the joy and profits of the game attracted other players who were much bigger than him and which he could never have beaten. The big companies were no match for Pace who could not offer his artists the contracts offered by the big ones. The game was lost from its very start. Let us not forget that there were no strict rules that could stop Black Swan’s top artists as Ethel Waters or Alberta Hunter to go and hunt other more lucrative contracts with Pace’s rivals. It is not difficult to see that those rivals were quite happy to welcome the stars of the Black Swan label especially in a market that was under constant pressure from the competition by the radio.

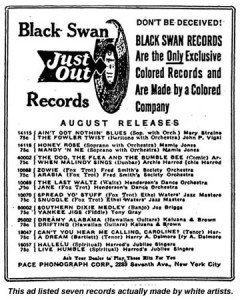

Even if afterwards it has been explained as a temporary measure to overcome financial difficulties, the betrayal of the basic premise that Black Swan would be exclusively black could only contribute in the end to the loss of reputation and good will in the artist community. The betrayal was twofold. In the first place, Pace concluded a partnership with a white entrepreneur (John Fletcher), to buy the bankrupt Remington Phonographic Company. It gave Pace the possibility of pressing his own records, but at the same time this business deal was not congruent with the starting ideal that the company would be exclusively black. In the second place, Pace (or was it Fletcher?) decided to reissue the songs that came with the takeover of Remington under the Black Swan label. Only, these were songs performed by white musicians. Pace however continued to underline in his advertising that the company was exclusively black. One example of an ad read as follows: “Black Swan. Don’t be deceived: Black Swan Records are the ONLY exclusive colored records and are made by a colored Company“. Below this ad were listed seven records of musicians with black sounding nicknames, but who were ….yes, white.

I think that we can accept the statement that the consumer didn’t hear the difference between a black and a white voice. There are indeed indications that the audience was not really bothering with this “deceit”, which again illustrates how artificial the colour line in music was and is. It is however much more plausible that this misleading was not really welcomed in the community of the artists, neither black nor white. The black could easily use it as an argument to close the door on the company because the argument of the exclusiveness did not hold any longer. The white artist was probably not always too pleased to see him/her promoted as a black artist.

This misleading was in no way a marginal event. Some authors (Andrew Scott) quote that about one third of the production was in fact a reissue of records made by white artists for other companies. Weusi (2004) writes: “Pace began to lose the respect and confidence of the musician community, and it became more difficult to produce a quality product“.

Let me come back then to my initial question: was the Black Swan Record label also a Black Swan event? Was its existence and swift disappearance unexpected? Did Black Swan have a huge impact? Can its rise and fall be rationalised ex-post, making it more predictable?

In the social, economic and cultural context of 1921 the establishment of a totally black music company can in no way be taken for granted. It testified of more than courage to engage in such an activity; combining courage, song-writing talent, business skills in one person who was on top willing to confront white hostility to show the viability of a business concept in a niche market that was still to be defined cannot be seen as a frequent event. This marks a score for the first criterion of the Black Swan theory: the emergence of the company was not expected.

What was perhaps less unexpected was the quick fall of the company. It is said that disasters are mostly the result of a matrix of concurrent events, but I feel that already from the start there were too many elements present in the company’s objective and strategy to make the bankruptcy after only 2 years not really a thunder strike in a clear blue sky. Probably, it testifies of my all too inadequate knowledge of the black activist movement, but I feel that the cultural goals of Pace didn’t bear enough potential to make the prime goal of a commercial enterprise realistic: turn out a profit, enough to keep the company running and pay its employees. Mamie Smith’s ‘Crazy Blues’ had shown that the black consumer community was enthusiastic for the popular blues. Just imagine how it must have felt for the black community to hear their own artists on this new technology. It must have felt like we first saw our photographs appearing on the internet in the early days. Pace should have taken this in account. The population which he most tried to reach was not open for the middle- and highbrow music that he wanted to promote.

The sudden fall of the Black Swan Label is thus not really congruent with the Black Swan theory.

But all this is too much criticism on the accomplishments of a man that I deeply admire, because what he realised can never be underestimated. His work was at the crossroads of business, political-economic emancipation and art. He broke down the barriers or certainly contributed significantly to the demolishment of the levees that kept the ‘dirty blues’ excluded from the popular and record market. It is the irony of history that the very popular music of the working-class population that he wanted to promote was finally marketed by white companies.

In this perspective, his role for the later music history is undeniable and incalculable. And this makes the Black Swan Record Label’s short existence to a very major event in the history of popular music in the 20th century. This marks certainly a score of congruence with the Black Swan theory.

What happened after the bankruptcy? Most of the Black Swan artists made their career on other labels. Ethel Waters had a brilliant career up until the fifties. Alberta Hunter was still singing in her eighties. Fletcher Henderson worked together in the thirties with Benny Goodman. And Harry Pace? He founded an insurance company which became the largest African-American-owned business in the North during the 1930s. Pace then moved to Chicago where he attended a college of law; he received his law degree in 1933. He opened a law firm in down town Chicago in 1942, and died a year later.

Sources :

– J.K. Weusi, Black Swan Records, at www.redhotjazz.com

– Black Swan Records, at www.blackpast.org

– Race Records, at www.pbs.org

– Davis & De Loo : Black Swan Records : From a Swanky Swan to a Dead Duck, 2002

– Co-workers in the Kingdom of Culture : Black Swan Records and the Political Economy of African American Music, D. Suisman, 2004

– Black Swan Blues : America’s first Motown, P. Slade, 2009

– Black Swan’s Other Stars, A. Sutton, 2007

– Selling Sounds, The Commercial Revolution in American Music, D. Suisman, 2009

– Recorded Music in American Life : The Phonograph and Popular Memory 1890-1945, W.H. Kenney, 1999

Hi Mike,

thanks for your reaction!

As for your question on a good biography on Mr Henderson, I have been able only to trace the following:

-The uncrowned king of swing: – Fletcher Henderson and big band jazz- Oxford University Press, 2005

(http://www.amazon.com/Uncrowned-King-Swing-Fletcher-Henderson/dp/0195090225)

You could perhaps also contact Alex van der Tuuk (paramountshome.org) who has done quite some research on recording activities in blues in the twenties, in cooperation with Guido van Rhijn (http://home.tiscali.nl/guido/).

Fletcher Henderson’s was not the original Black Swan Troubadors as an advertisement for such appears in the May 2, 1897, Boston Herald. The May Festival is the occasion and, “Something entirley new in these festivals will be the southern plantation scene presented by members of the Black Swan Troubadors, with songs by Prof. and Mrs. Tyler.” Also a book buplished in Kansas City, Mo., by the Burton Pub. Co., written by former vocalist, Melissa Fuell, reports that a Josephine Rivers, formerly of the Black Swan Co., will begin touring with the Blind Boone Concert Co. Josephine Rivers appears with the Boone Co. in several newspaper reports in 1902-03. Is there a good bio of Mr. Henderson that may tell how he came to use that particular name?