As Edward Comara points out in his Encyclopedia of the Blues (p. 995), it is quite normal that the blues singer in his capacity as African American bard deals with disasters of all different kind : incidental, long-term, accidental and natural. An analysis of the frequency of the disaster theme in blues songs and its evolution over time would learn a lot about the way that a disaster has been experienced on the individual and community level (see also the 3CD-Collection : People take warning, a collection of murder ballads and disaster songs originally released on commercial 78s between 1913 and 1938). The blues song is a means of transmitting messages between communities and over generations. This is especially true for the black population when it wanted to convey messages amongst it without the plantation owner being aware of it.

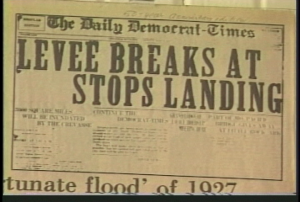

A well known example of a disaster topic in blues songs is the Mississippi River Flood of 1927 which was one of the greatest natural catastrophes that has struck the United States. This devastating event has been the subject in numerous songs, black and white, in the states directly hit by the disaster and in states beyond them.  “When the levee breaks”, which was on Led Zeppelin’s album IV in 1971, is a re-arrangement of the song written by Kansas Joe McCoy and his wife Memphis Minnie and recorded in 1929. It is probably the best known example of such a song.

“When the levee breaks”, which was on Led Zeppelin’s album IV in 1971, is a re-arrangement of the song written by Kansas Joe McCoy and his wife Memphis Minnie and recorded in 1929. It is probably the best known example of such a song.

The boll weevil disaster is another example but I consider it at the same time as of an entirely different nature. This devastating beetle was not only the subject of an enormous series of songs in many different versions (you can find an interesting overview of them here) – there is also the example of the artist who nicknamed himself as Bo Weavil Jackson) – but to some extent there exist arguments for the statement that this beetle even helped to shape the Mississippi Delta Blues. I’ll explain.

But firstly what is the boll weevil?

The boll weevil is a very small insect, a beetle, with a very typical long snout, which feeds itself from the buds and the flowers of the cotton plant. It settles itself in the young plant and in its growth it works its way out until finally the cotton boll drops off, all black. It is said that it originated from the Mexican region and crossed the Rio Grande near Brownsville in Texas in 1892. It took only 30 years to spread itself all over the cotton belt. Many economic studies have been conducted about the impact that this little insect had on the cotton agriculture and economy, both on the macro- as on the micro-level (see for instance Alan L. Olmstead, UC Davis & Paul W. Rhode, University of Arizona, 2008) and these studies seem to navigate between the theory of the extreme catastrophe to the theory that the boll weevil pestilence only lead to another balanced economic situation.

I think that in any case this tiny little insect shook up the social and economic life of the individual farmer in a drastic way. At the moment it became fully developed, it simply destroyed the crop, but already the anticipation of the arrival of the weevil in the years beforehand must have had a terrifying effect. It destroyed not only the crop itself; it also implied a devaluation of the land. Even if the rising price of cotton could offset somewhat the effect of the substantial reduction of the harvest, the spread of the boll weevil settled itself as a structural element of instability and uncertainty of a population which was already exploited to poverty in an unfair social structure based on sharecropping and tenancy. Left without any means to pay of their debts, the sharecropper and tenant were forced to leave the land and to migrate to another region or to look for work in a local factory. The increased supply of labour force however resulted in a decline in the wages and a worsening of the social conditions.

For those who stayed behind, their efforts to offset the impact of the boll weevil by an increase in production simply contributed to quicker soil erosion, thereby undermining the potential for the future.

It is thus not surprising that this little beetle was the main actor in many a blues song. Already in the early 1900s, it is said that Charley Patton wrote his version of the “Mississippi Bo Weavil Blues”, which was issued on record in 1929 under the cover name “The Masked Marvel“.

But there is more to the song than this.

The spread of the boll weevil followed a specific pattern from the South, Texas, more to the East and to the North. This impacted also the migration of the farmer population. The states of the Mississippi Delta, the region between the Mississippi and the Yazoo rivers, were invaded in a later stage. The soil of this region was very fertile: it was alluvial soil built up by the flooding of the rivers. This meant two things for the weevil: the flood reduced the territory where the weevil could hibernate (it needs leaf disposal), and the fertility of the soil meant that the crops would mature earlier in the year, leaving the weevil less chances to damage the cotton. The “wave of evil” (as it was called in the Congress in 1903) was slowed down by geographical conditions and by the biological characteristics of the insect. Tom Charlier (2007) draws attention to the fact that the boll weevil infestation drove tens of thousands of African-American sharecroppers in the delta. The Delta plantations could remain longer lucrative at a time when the little devil had ruined cotton harvests everywhere else. This migration influx created both the market and the creative environment for the development of the blues. It created a ready audience for musicians. There was money, and where there is money there is room for culture. Moreover, the migrated population was young, and this creates an energy and openness for change in itself.

But besides this, it can also be argued that the boll weevil stood for more than an insect. It could also be regarded as a metaphor, a symbol.

When Charley Patton wrote:

“Bo weevil, Bo weevil, where your native

Home? Lordie

Most anywhere they raise cotton

And corn, Lordie”

isn’t there an envy that shines through: the envy of the poor sharecropper or tenant that is bound to his land, whereas the boll weevil could spread and go where it wanted (Peterson, 2007)?

Other music critics (Smith, 2005) go even further and see the boll weevil as the symbol present in the African American tradition of a kind of trickster who rejects the social conventions and deceives everybody to obtain personal gain.

It is also striking that in the versions of the song by Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith the insect takes the form a man (“I don’t want no man to put sugar in my tea – that bug is so evil – I’m afraid he might poison me”).

All this would explain, according to Giesen (2011) why the boll weevil was such a popular subject, that was turned into a myth : the boll weevil helped to obscure the real problems of the cotton belt, not caused per se by the beetle, but more by the socio-economic structure of an unfair, feudal landowning system based on the ideology of the white supremacy and challenged by a decline of soil fertility, all this in confrontation with the ever growing economic supremacy of the industrialized northern States. The boll weevil myth accompanied the growth of the poor Southern states into the modern society that had found fixed soil in the northern states which profited the most (if not exclusively) from the benefits of the ‘roaring twenties’.

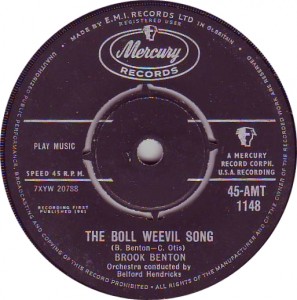

Anyhow, the boll weevil stays an actor on the scene also after the Second World War. Still in 1980 experiments were conducted on a large scale to eradicate the insect in whole regions. And the little beetle was not forgotten in the music sector either: in the beginning of the sixties the R&B star and singer/songwriter Benjamin Franklin Peay, better known as Brook Benton, scored a massive hit with “The Boll Weevil Song”. However, when listening to it, you will hear that it is already far off the sorrow and distress that was present in the earliest versions of the song. It sounded more of a distant narrative story about a past drama that had become part of the history than of an immediate threat to the public of the sixties.

hoe een kevertje een hele culturele evolutie kleur geeft!

Fascinating!