“Blues blows the vacuum tubes of the radiola” (radiola was the name that RCA gave to its early production radios). This could have been a title in the Chicago Defender journal of 1922. It could have continued saying that: “Since the intense and high pitch voices of some country blues artists blow out the vacuum tubes on radio transmitters, it has been decided to ban blues artists from the wireless”.

This is just a joke of course. Blues was not banned from the radio for that reason. The part of blowing the tubes however, is not a joke. As D.E. Kyvig observes ironically, the technical limitations of the early radio reshaped the music in the sense that it stimulated the development of the ‘crooning’ style: high sopranos and other intense voices had a tendency to blow out the vacuum tubes on early radio transmitters (Kyvig, Daily Life in the United States, 1920-1940, p. 79). It is funny to see the different ways that technology can impact musical styles, no? I see a smile on Hegel’s face in his grave as if he is saying: “I told you so! Technology determines Culture”)

But back to my original observation: blues was not participating in the radio hype that started in 1920. Why not? In fact, when one comes to reflect upon the matter a bit further, I would like to put forward another statement, which is more a personal hypothesis rather than an objective observation: It is quite astonishing that in the second half of the 1920s a market was opened for country blues artists in another segment of the new mass media entertainment sector: the record business. Was it not an anachronism to find on the shelves in the stores records containing a musical genre that clearly had its origins decades before and that found a buying public in a time period which without any doubt can be seen as the start of modern ages? After all, it is in the 20s that automobiles started to fill our streets (at least those in the US), that the movie was transformed from “a silent movie with a talking audience to a talking movie with a silent audience” (Robert Sklar, 1994). It was also in the 20s that gradually the mass consumption as we know it today began to take shape. The first self-service stores with automobile parking lots in the front were opened. They were called supermarkets. In 1927 the first man (Lindberg) did a solo and non stop flight from New York to Paris and became the first national radio star. The first home electrical appliances as vacuum cleaners and refrigerators were introduced on a large scale. The first deep frozen meals hit the tables, the human figure became a point of attention, mass-production of clothing and the standardization of fashion popped up, ….We can go on illustrating the important changes that took place in the American life in the 1920s which introduced the 20th century definitively in the modern times, changes which would only gain strength after the interruption of World War II.

Yet, despite all those tendencies to modernization, country blues with its origins in field hollers, work songs and spirituals found its way to the recording studio. The contrast couldn’t be greater, no? Why would a company try to sell this type of music which already then could be considered to some extent as ‘old fashioned’ in a society that was more and more characterized by a centrally defined mass culture and in which for instance Warner Bros. issued (in 1927) its first feature length “talking picture” and highly successful “The Jazz Singer”?

And yet, these are only contradictions at first sight. When one looks at the matter more in detail, the pieces of the puzzle all fit together perfectly. I’ll try to explain this in what follows and highlight why country blues was “waxed” but was not “wireless”.

The radio is a typical mass medium which even more than records aims at a broad public across geographical and social boundaries. Radio could be heard not only privately, but also publicly. A broadcast could go from one coast of the US to another coast. In the 1910s radio was a matter that was of interest for the military, the shipping business and amateurs who could play with this new technology to transmit messages (Morse), and later sounds, from one point to another. When the first commercial broadcasts were made in the beginning of the 1920’s they were financed by companies which had a small budget. It was only when sponsors began to see the role that radio could play in promoting products that those budgets could be increased. Given the liberal position of the government, the latter did little or nothing to intervene in the explosion of the radio stations other than trying to put in place a regulatory framework (Radio Act of 1927) for the use of the different frequencies used by an ever increasing number of radio stations, which were fighting amongst each other, and which were sometimes literally blowing each other out of the air. The companies had to get their income from sponsors and thus, they had all interest in reaching as large an audience as possible. They could in no way shock their audience by broadcasting music that was not socially accepted. In this respect, it is illustrative to note that the companies did not rely on direct advertising for their products, which would be seen as to intrusive for the public. They advertised indirectly by trying to link their name to a radio station or program.

Those companies were white owned. To fill the time on the air, next to the broadcast of mainly political and sports events, they played classical music, semi-classical music, dance music and white country music. The tunes had to be clean and entertaining without attracting controversy. Very often, the music was performed live, at first even by amateurs who volunteered and were all too happy to have their musical “talent” broadcasted. Live music by amateurs also allowed avoiding a debate on paying copyright fees to the ASCAP (American Association of Composers, Authors and Publishers).

The dance music and vocal work that was played had African American roots, but the stardom was reserved for the white performers. There was a strong resistance against jazz music which was considered as being indecent. Contrary to the blues however, jazz managed rather swiftly to acquire a status of respectability. An important role in the integration of black jazz into the white mainstream music has been played by Paul Whiteman and his Orchestra, who proclaimed himself as the “King of Jazz” and made fame by his first performance in 1924 of the jazz-influenced “Rhapsody in Blue” composed by Gershwin. His music was played all over the states. It paved the way for the rare black star jazz artists Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington.

Contrary to the blues, jazz had also a social basis which could promote it. The roaring twenties (also called the Jazz Age) were infused by the rebellion of a group of young, white adults (“sheiks” and “flappers“) who questioned the moral Victorian code of their parents by adhering to a music style that was loose and spontaneous. These ‘white negroes’ played an important role in the process of infusion of the mainstream white culture with black elements of Jazz and Ragtime. However, in this process of expropriation of the black culture, the inevitable compromise happened which streamlined the original roots music to make it fit more the dominant culture. Its style was made more acceptable to the white audience, and for a start: it were white performers who brought the black music (do your thoughts also flow to the birth of rock & roll in the fifties?)

The softening of the jazz was especially clear in the 1930’s when it evolved to the swing-jazz which was functional in cheering up the crowds after the Great Depression.

The radio waves were thus ruled by the whites. This racial segregation in the radio industry didn’t mean that blacks were totally excluded. In her article “African Americans and Early Radio” (1999) Donna Halper highlights the role that has been played by both early black technicians and musicians in this industry. She points out that some local stations did indeed broadcast black music. She has even indications that already in 1914 a white radio amateur sent out a concert of his favourite W.C. Handy.

However, the broadcasting of black music was only of an occasional nature and was especially present in the most hospital cities for black music as New York and Chicago. It happened that Pinetop Smith (boogie woogie style blues pianist) or Lonnie Johnson (crooning blues), or even Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey and Leroy Carr were on the air, but this was more of an exception that confirmed the general rule that radio industry was a white industry. Duke Ellington managed to establish a stardom, but that was in no small way due to the fact that he had an aggressive white promoter (a Jewish immigrant – the (Jewish) Chess brothers would do the same later with a.o. Muddy Waters: minorities found each other!). The hundreds of blues (country) artists were completely ignored.

The establishment in the second half of the 1920’s of national broadcasting networks (NBC and CBS) implied even a stronger exclusion of the black population from the radio up to the point that in the 1930’s they were in practice almost totally absent. If black musicians had still small opportunities to appear on local stations, these opportunities vanished when the national networks became operational. This absence of black entertainment also implied a lack of interest of the black population in the radio as a mass medium.

It is illustrative that the only black announcer (quoted by Donna Halper) employed by a white radio station (WCAP, Washington), had to use the back entry of the building, together with the black cleaning staff. This says it all about the status of the black population in the radio industry.

And yet, country blues was to be found on another instrument of the upcoming mass media industry: records. This should not be surprising if one realizes that the marketing strategy in the record business could take into the account the geographical and racial characteristics of the buying public. The separate race records could be specifically promoted to the Southern states (using for instance ads in the Chicago Defender) whose population was as a whole much poorer than the more advanced northern states. All of the technological and social changes that were taking place in the roaring twenties were in the first place an urban, northern phenomenon. Blacks in the Southern States could buy the black music by a mail order system of northern based, white companies. Country blues found also its market in the poor ghettos of the northern cities of Chicago and Detroit crowded with immigrants looking for a cultural link with their roots.

The recording of country blues can thus be seen as a way for white companies to make one sector of the mass media business profitable, especially in the face of the fierce competition of the radio. Black culture became a sector of exploitation by white entrepreneurship and was literally victim of the theft of its music and its copyrights by white talent scouts (and even black ones as was the case for Mayo Williams when he was employed for Paramount) and white managers.

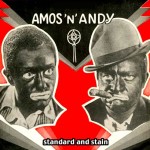

The immense popularity of the radio series ‘Amos ‘n Andy’ at the Chicago WMAQ starting in 1928 can be seen as a perfect illustration of the dominance of the white population in a racially segregated entertainment industry. This comedy series, inspired by the minstrel shows and the black face performances in the 19th century, told the story of two black men from the country who were confronted with the novelties of the urban and modern life in Chicago. The mockery of which they were subject was certainly not typical for the black population – all immigrants and ethnic groups were subjected to this “cartooning” activity – but it illustrates perfectly the story told above. The role of Amos and Andy was not played by blacks but by whites! And most ironically, the comedy series was also very popular amongst the black population.

The country blues was thus aiming at a market which was both socially, racially and geographically well delineated and different than the one for which the 20th century modern times, characterized by standardization and mass culture and consumption had started. Radio played a more prominent role in this process than records.

The integration of blacks in the radio industry would only slowly evolve. The first all black format radio was probably the white owned WDIA in Memphis in 1948 (D. Halper). The first black owned radio station only went into the air in 1949 (WERD, Atlanta).

But let us not forget the famous King Biscuit Time, the longest running daily radio broadcast in the US, which broadcasted the first time on 21 November 1941 in Helena and featured African American blues artists as Sonny Boy Williamson (II), and was the starting point of many great blues artist careers as for instance for Riley B. King, better known as the Blues Boy from Beale Street, B.B. King. The radio platform KFFA was the only station to bring music by African Americans, reaching an audience even into the Mississippi Delta. It was sponsored by …. the local flour company, King Biscuit Flour, a local grocery distributor. White flour sponsoring black music. No doubt, the King Biscuit Flour had in mind also the black female servants baking the bread for their white employers. Which brings me back to my starting point of this post…..

Thanks for your information! I really liked it.

My brother suggested I might like this blog. He was entirely right. This post truly made my day. You can not imagine just how much time I had spent for this information! Thanks!