One can seriously ask the question to which degree the emergence of the recorded blues could not be considered as a pure consequence of luck following risk taking by white entrepreneurs driven by pure financial and economic necessity! When the singer, songwriter and vaudeville/minstrelsy artist Perry ‘Mule’ Bradford finally succeeded in 1920 to convince Okeh-records (label of the General Phonograph Corporation) to wax Mamie Smith’s ‘Crazy Blues’, he took advantage of the financial and economic clouds that were gathering for the record companies at the threshold of the roaring twenties. Something needed to be done to have the sun shine again on the landscape of the record business. It was totally unexpected that Smith’s record would sell more than 7.500 copies in its first week and a million copies in its first year, mainly to black customers. Okeh took a substantial risk when launching the record on the market, but it had very little other opportunities for survival on a market that was dominated by two giants (Victor & Columbia Records). The economic depression in the first years of the twenties and the coming rivalry from the radio didn’t leave many other options than the search for niche markets on a global market that was saturated with records of classic & white popular music.

As posted earlier, the record industry started its development some twenty years after the invention of the phonograph in 1877 by Edison. From 1888 onwards, it had been possible to produce phonographs in sufficient quantities to make the marketing of the sound cylinders commercially viable. Columbia and Edison’s company shared the market, but competition entered when the Victor Company introduced a new technology replacing the vertical registration of sound waves by the flat disc, which was commercially much more attractive than the cylinders. Columbia bought a patent on the technology and from 1902 Columbia and Victor established a monopoly with their laterally produced discs. The flat disc allowed also a much easier storage and longer musical performances could be recorded. The success was guaranteed, especially because the patent forced the other companies to use the old technology.

In the second half of the 1910s the sky became the limit for the record business. The patent on the new technology had expired since 1914 and a decision of the U.S. Supreme Court moreover ruled that the new technology had to be open to all record companies (we have witnessed this kind of struggle over formats also in recent years in the audio and video sector). Whilst in 1914 only some half a million Americans owned a phonograph player, in 1919 this number had risen to more than 2.2 million! Some 46 companies were in 1916 in direct competition for the dollars that the customer was eager to spend with pleasure, since dance and music were immensely popular. The war contributed to the hype as the live performances were hit by the flow of artists towards the army services. Music on record dominated the entertainment market (S. Filzen, 1998)

The market became however over saturated. Before 1920 record companies focused on the white immigrant population and offered them white music. White music for a white population. But the demographic conditions changed and the Great Migration to the Northern Cities increased the importance of the black population. Moreover, the war ended the white immigration from Europe. The market changed. Perhaps it was time to sell black music to black immigrants?

A quick solution had thus to be found otherwise financial disaster would strike for the record companies.

It is in this context that the emergence of the record company Paramount is to be seen (note that the record company Paramount had (then) nothing to do with the picture Company from Hollywood that has the same name).

Paramount has both been a blessing and a curse for the blues music. A blessing, of course, because after all, it has left us with a legacy of artists which is substantial. If it had not been for Paramount, we would probably not have heard of Blind Lemon Jefferson or Charlie Patton. At the same time however, it has also been a curse because at the end of the day, the way it conducted business was nothing short of clumsiness, short-sightedness, mismanagement and exploitation of the black musicians.

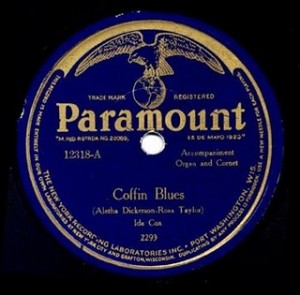

The company is also veiled in a fog of legends and mystery as there exists no consolidated estate that has been left. Extensive research is being done on what they produced, and the finding of a 78er issued by Paramount is a real source of exaltation and a gold mine for him or her who tumbles on such a rare disc. The auction prices for the Paramount blues records from the twenties easily surpass 10.000 $, especially when there are only one or several known copies. Some people make a living from these rarities. I read the story even of people diving in a lake nearby the place of the Paramount production plant to look for master discs on the bottom of the lake (without any success though).

It all started in 1886 as a company in Sheboygan, a place near the Lake Michigan, just above Milwaukee, that wanted to produce … chairs. The company grew fast in his first decades, despite the misfortune of some fires. The key to their success was diversity, as next to chairs it also went into the knitting business and launched itself in the manufacturing of canning machines (not yet the canning of music…). It was a logical step for a company that was in the furniture sector to expand their product line towards the manufacturing of cabinets for phonographs, the new booming business. Phonograph cabinets were a kind of status symbol from the early 1900s. However Paramount had to compete in that market segment with the Edison Company that had started producing its own cabinet. As a response, the Wisconsin Chair Company made the next move to secure its position: the production of both phonographs as records. It was 1917 when the New York Recording Studio Laboratories were founded. However, the experience the company had in this business was nil, nothing….not in the music sector itself, not in the distribution, not in the engineering, not in the wholesale.

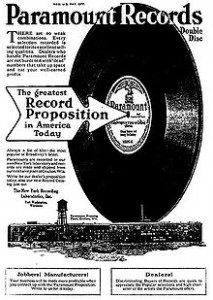

As the other companies, they targeted the white population sector with crooners and popular music. However, they came too late in this sector that was already occupied by Victor and Columbia who had contracted the most famous artists. Those two giants also monopolized the distribution channel. This way, Paramount started off very badly: it didn’t have any experience, and didn’t manage to get enough capital to get the necessary coverage of the market, lacking the artists and the distribution channels. Paramount was an amateur in this market and disaster was almost inevitable. When the economic recession struck in the first years of the twenties, and when prices dropped, it became only worse…

And then there was the “Crazy blues” which struck as a lightning in a clear blue sky. Okeh had taken the risk to dig into a niche market and it was a huge commercial success. Paramount reacted adequately and saw that a potential gold mine was there to be exploited, and it would become a market leader in the black music industry (though it never gave up completely the white music). Initially, Okeh promoted their products as ‘coloured records’, but very soon the black newspaper ‘The Chicago Defender’ (founded in 1905 for the black population in North and South”) coined the term ‘race records’, which allowed a clear separation from the white market. The records were issued in separate series to aim specifically at the demographically and economically more and more important black segment of the population. Whereas in the field white and black music were very often intertwined, the official recorded music of whites and blacks went separate ways.

At the edge of bankruptcy, Paramount entered the race record market in 1922 when it recorded Alberta Hunter, and already a year later it had made fame as leading company in this part of the music sector. However, what then follows is nothing less than pure cheating of not only the black artist, but also the distribution channels and even the customers!

For a start, the artists were very poorly rewarded for their work, if they got anything at all. Their contracts (if any was put on paper) were drafted in a way that pecuniary virtually nothing was left over after deduction of all the expenses. Since the artist was mostly illiterate, who was he/she to check? The blues man was already very happy that his work made it to a record. Royalties were carefully kept by the record company or by the talent scout. Mostly, the recorded artist received a lump sum for his work, which was by the way substantially lower than the one that the white artist earned. Sometimes the disparity was as big as 1 to 50 between the white and the black performer.

Secondly, Paramount put in place a distribution channel that was as cheap as possible, using a mail order system (the bulk of their customers were located in the South where they had no access to white shops, which most often would not offer the ‘race records’ for sale), or a door to door delivery in the Northern Cities. But can we blame it for cutting costs? No, but we can hardly appreciate some of their marketing techniques which came down to pure cheating. The story goes that when the records would be on sale in general department stores, Paramount hired a group of black people to come in group to a store making the store owner believe that there was a big demand for the Paramount product.

Thirdly, the customer itself was subject to pure disrespect. Paramount had the habit of proceeding to a kind of recycling of their products issuing songs on secondary labels, which were printed with even less sound quality than on their main catalogue. When in 1925 the electrical recording technique was introduced (a by-product by the way of the military research into wireless radio transmission during World War I), Paramount was not hesitating to print on their record labels that the song was electrically recorded, whilst in fact Paramount was only very slow to adopt the new technology.

Their recording techniques were as a whole very poor. You need to realise that Paramount was located in a wholly white community in the North, and that it had all interest to hide away from the population where their recording studios and pressing plant were located that it was recording black artists. They carefully kept it hidden away from the public eye. The result was that the studio locations were very poor. Some were located in places near a rail road: each time a train passed by, the recordings needed to be stopped. In other locations (sometimes rented places in a hotel), it was so hot that the original waxes just melted: they had to be put on ice cubes to be transported to the pressing plants. Those plants were no example of up to date technology, using still mechanical procedures whilst other plants already had integrated electric driven motors. It is a damned shame that the recording quality of the Paramount was so bad, with so much surface noise.

Cost saving was again high on the agenda at the expense of the quality of the music. The fact that it was not uncommon to recycle the material of the master recordings, which contained cupper, has also contributed to the later mystery of the precise output of Paramount.

After all, it can be seen as a sheer miracle that Paramount was active in the music business until 1932. Their management was a complete failure. At first it had hired, on a free lance basis, the black ex sports writer Mayo Williams.  He had the advantage of loving the (black) music and being black. He was the entry gate to the black musicians, Paramount’s bridge to its pool of talent, even if Williams himself followed the same techniques as the company to keep royalties for himself. Williams was the link to the talent that circulated in Chicago, he was also the one that appreciated the talent when he heard it. He didn’t get however a large mission budget to go and look for talent in the Southern States; this was left to local talent scouts (H.C. Speir was one of them, thanks God!). But Williams was replaced in 1927 by a white recording director, who even more than the others, considered the blues music as just any other product that needed to be sold at the lowest possible cost, at the same level as soap or any other commodity. Paramount lost touch overall with the musical community and got in a vicious circle: no income, no money to attract talent. Its appeal was totally lost. When on top their big star Blind Lemon Jefferson died in mysterious circumstances in 1929, the end was near. The financial losses which were already significant just kept on accumulating. It didn’t help that even more savings were made when it used the old knitting factory of the company as a recording studio! When the new management turned to issue also hillbilly as a way to turn the tide, it was too late. Paramount had become a place where only mediocre talent was willing to record.

He had the advantage of loving the (black) music and being black. He was the entry gate to the black musicians, Paramount’s bridge to its pool of talent, even if Williams himself followed the same techniques as the company to keep royalties for himself. Williams was the link to the talent that circulated in Chicago, he was also the one that appreciated the talent when he heard it. He didn’t get however a large mission budget to go and look for talent in the Southern States; this was left to local talent scouts (H.C. Speir was one of them, thanks God!). But Williams was replaced in 1927 by a white recording director, who even more than the others, considered the blues music as just any other product that needed to be sold at the lowest possible cost, at the same level as soap or any other commodity. Paramount lost touch overall with the musical community and got in a vicious circle: no income, no money to attract talent. Its appeal was totally lost. When on top their big star Blind Lemon Jefferson died in mysterious circumstances in 1929, the end was near. The financial losses which were already significant just kept on accumulating. It didn’t help that even more savings were made when it used the old knitting factory of the company as a recording studio! When the new management turned to issue also hillbilly as a way to turn the tide, it was too late. Paramount had become a place where only mediocre talent was willing to record.

In 1932, the game was over. Unlike other companies, which also suffered from the Great Depression, Paramount didn’t find any candidate for take over. It couldn’t exactly offer its reputation as an asset, on the contrary. It is said that the angry employees at the shut down just threw master copies (which were not yet sold as scrap metal) into the river.

I may have sounded a bit too negative about Paramount. But as I stated above, it had also its good sides. If abstraction is made from its motives, and if we ignore its cheating practices and text book examples of bad management, we can still today – through all the enormous surface noise of the rare 78s that have surfaced – hear the strength of the raw delta blues. And we can only be grateful for that.

Paramount had forced Skip James to compose in the studio in a mere 3 minutes time a copy of the hit record distributed by Okeh called “44 blues” by Roosevelt Sykes, but we have to be thankful in the end that Skip James’ “22-20” blues was recorded after all, even if it was financed by the profits made by the mother company in the production of chairs. We have to be thankful that the Wisconsin Chair Company took the decision in 1917 to expand its activities from furniture, canning machines and knitting to the marketing of blues. It helped to knit a great deal of the history of blues.

Your articles are so good!