The name “John Hammond” should be carved in concrete in the music history of the 20th century, yet, I bet that this name won’t even ring a bell with most of you. And yet, there is so much to be told about John Hammond.

There is a John Hammond Junior and John Hammond Senior, and although the son makes his own way in live, independent from the merits of his father, he can’t deny the family roots.

The son, John Paul Hammond is a very productive and talentful blues (mainly acoustic) guitarist and singer, born in 1942 and hooked on the blues since he heard Jimmy Reed, who was very popular in the fifties for his lazy style of singing and playing as a one man band both guitar and harmonica. From the start of his career in the beginning of the sixties until today Hammond has recorded over 30 albums, and it is safe to say that he is the only artist who can rightfully claim that he has jammed together for a couple of evenings with both Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix in the famous Gaslight Café in New York in 1967 (interview with John Hammond Jr.). John Paul Hammond acknowledges that the pre-war blues singers whom he admires so much were in the first place professional entertainers who had a large repertoire that surpassed the sole blues. The term blues was a marketing instrument for the white record companies executives. In his approach to music he backs up the words of his father in his memoires that he didn’t hear any colour line in music, and he quotes Howlin’ Wolf who had a big admiration for the (white) country music and more particularly for the yodeling voice of the country star Jimmy Rodgers. Only, Howlin’ Wolf couldn’t yodel, only …howl…

The marks that his father, John Henry Hammond II (born 1910) left on the 20th century music history are enormous. In a previous post, I highlighted the role of H.C. Speir in the talent scouting and production of many of the most famous pre-war blues artists. The role of John Henry Hammond II was even more important as it included not only blues but also jazz, swing, folk and rock. He was unique in many respects.

For a starter, he was one of the heirs of the Vanderbilt fortune, through his mother’s side. The fortune of the Vanderbilt family, acquired in shipping, railroads and real estate, largely collapsed in the midst of the 20th century. Nevertheless, it remained in the top 10 of the richest families. The name Gloria Vanderbilt as designer and perfume producer sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

Though his family tried to push the young John Henry into the corsage of what can be expected of a family of this social status with tentacles in the jet set of politics and economics, and tried to interest him in the classical music (violin and piano), John Henry was much more keen on the music performed by the black household personnel. When on top of that he heard Bessie Smith sing in 1927, the switch was turned forever. He left his academic studies and went straight into the music business, first as a critic and journalist.

What he did since then is just one long fairy tale of what a man can accomplish in a life time.

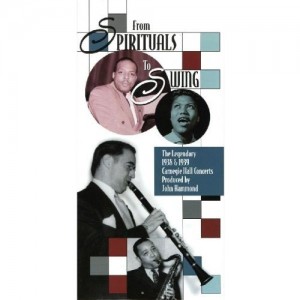

He started in his own way a fight against the injustice done to the black race. In his memoirs he explains: “To bring recognition to the Negro’s supremacy in jazz was the most effective and constructive form of social protest I could think of”. His leitmotif throughout was the integration of the races, not only on the social level, but also on the cultural level. It is hard to underestimate the importance of the concerts “From Spirituals to Swing” which he organized in 1938 and again in 1939 at the Carnegie Hall, the concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York.  His objective was to show the richness that America had to offer through the splendor of the black music, starting historically from the spirituals, over the blues to the jazz, swing and the boogie woogie. For the first time ever, that December 23rd 1938 he brought together not only a racially mixed audience, but also a racially mixed set of stage performers. It needs not to be said that this initiative was not on the priority list of the white population. It was only with the help of the Communist Party that John Hammond managed to get enough money together to organize the event which united names as Ida Cox, Big Joe Turner, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the Count Basie orchestra, Sonny Terry, and Big Bill Broonzy. He had called in Broonzy as a replacement for Robert Johnson who was on his initial list, but he found out that he had been murdered some time before (I remember having read somewhere that he played Robert Johnson’s records before the live audience – this must have been a sensation !). The concert also featured the Golden Gate Quartet, “a gospel group who had been crucial in the crossover of African-American performers to the mainstream, not just in terms of their acceptance as entertainers, but more signficantly a recognition that blues, jazz and gospel were fundamental components of contemporaneous American culture” (Hugh Gregory in : RoadhouseBlues, p. 77).

His objective was to show the richness that America had to offer through the splendor of the black music, starting historically from the spirituals, over the blues to the jazz, swing and the boogie woogie. For the first time ever, that December 23rd 1938 he brought together not only a racially mixed audience, but also a racially mixed set of stage performers. It needs not to be said that this initiative was not on the priority list of the white population. It was only with the help of the Communist Party that John Hammond managed to get enough money together to organize the event which united names as Ida Cox, Big Joe Turner, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the Count Basie orchestra, Sonny Terry, and Big Bill Broonzy. He had called in Broonzy as a replacement for Robert Johnson who was on his initial list, but he found out that he had been murdered some time before (I remember having read somewhere that he played Robert Johnson’s records before the live audience – this must have been a sensation !). The concert also featured the Golden Gate Quartet, “a gospel group who had been crucial in the crossover of African-American performers to the mainstream, not just in terms of their acceptance as entertainers, but more signficantly a recognition that blues, jazz and gospel were fundamental components of contemporaneous American culture” (Hugh Gregory in : RoadhouseBlues, p. 77).

The concert, which following its huge success in 1938 was repeated in December 1939, is to be considered as a milestone in the musical history of the blues and jazz music of the 20th century, and also as a key event in the history of the race relations in the United States.

Hammond tried to realize the dream of a racially integrated society not alone through his political, left wing ideas, but also and foremost through the fostering of active integration in the music. Not only did he for instance organize Benny Goodman’s Band, he also persuaded Benny Goodman to hire black musicians, one of them being Charlie Christian, a key figure in the development of the electric guitar.

Hammond’s musical accomplishments weren’t limited however to those events. He brought Billie Holiday from Harlem into the record studio, and invited the Count Basie Orchestra from Kansas to New York. In the fifties he discovered Aretha Franklin when she was only a young gospel singer. And in 1961 he heard a young man, called Robert Zimmerman, playing the harmonica. He contracted him to the Columbia Records Company despite the protest of its white executives. Luckily he won the battle with these CEO’s, otherwise we would have never heard of Bob Dylan. In 1961 John Hammond was also the drive behind the republication of the work of the great Robert Johnson (some 30 years later his son promoted Robert Johnson once more). Hammond is also to be credited for the success of the first (1983) and some later albums of Stevie Ray Vaughan (with a little help from his son John Hammond Jr). He also sparked the career of Leonard Cohen and Bruce Springsteen…

He died at the age of 77, following a series of strokes.

It is my personal guess that his fight for racial integration was a kind of overcompensation as the child rebel in the family, and a struggle with the legacy of his Vanderbilt’s roots. He also used the music as an instrument of social protest, whilst the artists themselves did not aim at social revolt and considered their music in the first place as a way to earn money and to entertain people. At the end of the day, and whatever his personal explicit or implicit drives, the legacy he left for the 20th century blues, jazz, folk and rock music is huge. As an author writes in his biographical notes: “blues-loving Vanderbilt heir seemed to know what America wanted to hear before America knew it“.

Автор предоставляет анализ достоинств и недостатков различных подходов к решению проблемы.

great submit, very informative. I ponder why the other experts of this sector don’t notice this. You should continue your writing. I’m confident, you’ve a huge readers’ base already!

Good day! I just would like to give you a huge thumbs up for the excellent info you have right here on this post. I am returning to your site for more soon.

Статья предлагает глубокий анализ проблемы, рассматривая ее со всех сторон.

Статья предоставляет информацию из разных источников, обеспечивая балансированное представление фактов и аргументов.

Статья содержит сбалансированный подход к теме и учитывает различные точки зрения.

Я хотел бы выразить признательность автору за его глубокое понимание темы и его способность представить информацию во всей ее полноте. Я по-настоящему насладился этой статьей и узнал много нового!

What’s up to every single one, it’s really a good for me to pay a visit this website, it consists of helpful Information. Это сообщение отправлено с сайта https://ru.gototop.ee/

Улучшение поведенческих факторов с помощью sitegototop.com Sitegototop.com помогает не только увеличить трафик, но и улучшить поведенческие факторы. Продолжительность сеансов, количество просмотров страниц и другие показатели могут повлиять на ранжирование сайта в поисковых системах. Настройка кампаний таким образом, чтобы трафик выглядел естественным, помогает улучшить эти метрики.

Позиция автора остается нейтральной, что позволяет читателям сформировать свое мнение.

Читателям предоставляется возможность ознакомиться с различными аспектами темы и сделать собственные выводы.

I read this post completely concerning the resemblance of hottest and earlier technologies, it’s remarkable article.

Очень интересная статья! Я был поражен ее актуальностью и глубиной исследования. Автор сумел объединить различные точки зрения и представить полную картину темы. Браво за такой информативный материал!

Heya i’m for the first time here. I found this board and I find It truly useful & it helped me out a lot. I hope to give something back and aid others like you helped me.

Thanks for every other informative website. Where else may just I get that type of information written in such a perfect method? I have a venture that I am simply now running on, and I have been on the glance out for such info.

Статья содержит подробное описание событий и контекста, при этом не выражая пристрастие к какой-либо стороне.

Какие альтернативы существуют у sitegototop.com? Существуют и другие сервисы для увеличения посещаемости сайтов, такие как BuyTraffic, Websyndicate и другие. Однако sitegototop.com отличается более гибкой системой тарифов и простотой использования. Выбор между сервисами зависит от потребностей клиента и его бюджета.

Очень интересная статья! Я был поражен ее актуальностью и глубиной исследования. Автор сумел объединить различные точки зрения и представить полную картину темы. Браво за такой информативный материал!

Мне понравилась балансировка между теорией и практикой в статье.

Excellent pieces. Keep posting such kind of info on your blog. Im really impressed by it.

Я бы хотел отметить качество исследования, проведенного автором этой статьи. Он представил обширный объем информации, подкрепленный надежными источниками. Очевидно, что автор проявил большую ответственность в подготовке этой работы.

Статья предлагает объективный обзор темы, предоставляя аргументы и контекст.

Я просто не могу пройти мимо этой статьи без оставления положительного комментария. Она является настоящим примером качественной журналистики и глубокого исследования. Очень впечатляюще!

Статья представляет разнообразные аргументы и позиции, основанные на существующих данных и экспертном мнении.

Помогает ли накрутка посещаемости увеличить число подписчиков? Если сайт предлагает подписку на рассылку или сервис, увеличение посещаемости может привести к росту числа подписчиков.

Статья представляет различные аспекты темы и помогает получить полную картину.

Автор статьи предоставляет информацию, основанную на различных источниках и экспертных мнениях.

When someone writes an post he/she keeps the thought of a user in his/her mind that how a user can be aware of it. Therefore that’s why this post is great. Thanks!

Heya this is somewhat of off topic but I was wondering if blogs use WYSIWYG editors or if you have to manually code with HTML. I’m starting a blog soon but have no coding know-how so I wanted to get advice from someone with experience. Any help would be greatly appreciated!

I was suggested this web site by my cousin. I’m not sure whether this post is written by him as nobody else know such detailed about my trouble. You are incredible! Thanks!

Как накрутка посещений влияет на рекламные доходы? Сайты, которые зарабатывают на рекламе, могут получить дополнительную прибыль за счёт роста посещаемости. Однако важно следить за качеством трафика, чтобы не нарушать условия рекламных партнёров.

What i do not realize is in fact how you’re now not really much more well-favored than you may be right now. You are so intelligent. You understand therefore considerably when it comes to this matter, made me in my opinion believe it from a lot of varied angles. Its like women and men are not involved until it is one thing to do with Girl gaga! Your individual stuffs excellent. Always maintain it up!

Thanks for the marvelous posting! I seriously enjoyed reading it, you are a great author. I will be sure to bookmark your blog and will often come back down the road. I want to encourage you continue your great job, have a nice morning!

WOW just what I was searching for. Came here by searching for keyword

Helpful information. Fortunate me I found your web site accidentally, and I’m stunned why this twist of fate did not came about in advance! I bookmarked it.

Автор подходит к этому вопросу с нейтральной позицией, предоставляя достаточно информации для обсуждения.

Автор статьи предоставляет информацию с разных сторон, представляя факты и аргументы.

Автор умело структурирует информацию, что помогает сохранить интерес читателя на протяжении всей статьи.

Статья представляет интересный взгляд на данную тему и содержит ряд полезной информации. Понравилась аккуратная структура и логическое построение аргументов.

Great goods from you, man. I have take into accout your stuff previous to and you’re just extremely fantastic. I actually like what you have got here, certainly like what you’re stating and the way in which in which you assert it. You make it entertaining and you continue to care for to keep it wise. I can not wait to learn much more from you. That is really a wonderful web site.

Статья помогла мне лучше понять контекст и значение проблемы в современном обществе.

Автор старается оставаться объективным, что позволяет читателям самостоятельно оценить представленную информацию.

hey there and thank you for your information – I have certainly picked up something new from right here. I did however expertise a few technical points using this website, as I experienced to reload the site a lot of times previous to I could get it to load correctly. I had been wondering if your hosting is OK? Not that I am complaining, but sluggish loading instances times will very frequently affect your placement in google and could damage your high-quality score if advertising and marketing with Adwords. Anyway I am adding this RSS to my email and could look out for much more of your respective interesting content. Ensure that you update this again very soon.

Your mode of explaining everything in this article is genuinely good, every one be able to easily understand it, Thanks a lot.

I was very pleased to find this great site. I need to to thank you for ones time for this fantastic read!! I definitely really liked every little bit of it and i also have you book-marked to see new stuff in your site.

Для кого предназначен сервис sitegototop.com? Сервис будет полезен владельцам сайтов, блогов и интернет-магазинов, которые хотят быстро увеличить посещаемость своих ресурсов. Он особенно популярен среди тех, кто только начинает развивать свой проект и стремится улучшить его видимость в поисковых системах. Накрутка трафика может также быть интересна маркетологам, которые работают над временными рекламными кампаниями и нуждаются в быстром росте показателей.

SiteGoToTop.com для повышения доверия к сайту. Когда сайт получает много посещений, это создает видимость популярности и доверия. Сервис SiteGoToTop.com позволяет увеличить количество посетителей, что способствует укреплению авторитета сайта как среди пользователей, так и среди поисковых систем.

Краткосрочные и долгосрочные стратегии с SiteGoToTop.com. SiteGoToTop.com подходит как для краткосрочных акций, направленных на быстрый рост трафика, так и для долгосрочных стратегий повышения видимости в поисковых системах. Гибкость настроек позволяет адаптировать сервис под любые цели.

Преимущества использования sitegototop.com. Одно из главных преимуществ сервиса – это быстрый результат. Уже в первые дни после начала кампании сайт может получить значительное увеличение посещаемости. Это помогает улучшить позиции в поисковых системах и увеличить доверие со стороны потенциальных клиентов. Кроме того, сервис предлагает гибкие настройки, которые позволяют выбрать оптимальный вариант накрутки для конкретного проекта.

Как анализировать результаты использования SiteGoToTop.com? После использования SiteGoToTop.com важно анализировать результаты через метрики, такие как время на сайте, просмотры страниц и конверсии. Это поможет понять, насколько эффективно использование сервиса и какие аспекты стоит улучшить в будущем для достижения более устойчивых результатов.

Как использовать SiteGoToTop.com для роста блога?

Преимущества использования sitegototop.com для SEO. Увеличение трафика через sitegototop.com может положительно повлиять на SEO показатели сайта. Повышение числа посещений способно улучшить позиции в поисковой выдаче, так как поисковые системы учитывают трафик как один из факторов ранжирования. Это делает сайт более заметным для потенциальных клиентов и пользователей.

География посетителей на sitegototop.com. С помощью sitegototop.com можно настраивать географию посетителей, что позволяет привлекать трафик из нужных регионов или стран. Это особенно важно для локального бизнеса или сайтов, ориентированных на конкретные рынки. Например, если ваш сайт работает для аудитории из России, можно выбрать преимущественно российский трафик, что улучшит его релевантность для поисковых систем.

Как сервис помогает новым брендам? Молодые бренды могут быстрее получить внимание аудитории, создавая эффект популярности благодаря высокому трафику на их сайт.

Зачем использовать накрутку посещений через sitegototop.com? Владельцы сайтов часто сталкиваются с необходимостью привлечения новых пользователей, но естественный трафик может нарастать слишком медленно. Сервис sitegototop.com позволяет быстро увеличить количество посещений, что может улучшить ранжирование в поисковых системах. Это дает возможность быстрее достичь желаемых результатов, таких как рост продаж, увеличение аудитории или повышение узнаваемости бренда.

Мне понравилось, как автор представил информацию в этой статье. Я чувствую, что стал более осведомленным о данной теме благодаря четкому изложению и интересным примерам. Безусловно рекомендую ее для прочтения!

Я очень доволен, что прочитал эту статью. Она не только предоставила мне интересные факты, но и вызвала новые мысли и идеи. Очень вдохновляющая работа, которая оставляет след в моей памяти!

Статья представляет объективную оценку проблемы, учитывая мнение разных экспертов и специалистов.

Автор предлагает реалистичные решения, которые могут быть внедрены в реальной жизни.

Keep on writing, great job!

Fantastic items from you, man. I’ve keep in mind your stuff previous to and you are just too magnificent. I really like what you have received right here, really like what you are stating and the way by which you assert it. You are making it enjoyable and you continue to care for to stay it smart. I can’t wait to learn much more from you. This is really a tremendous web site.

Я чувствую, что эта статья является настоящим источником вдохновения. Она предлагает новые идеи и вызывает желание узнать больше. Большое спасибо автору за его творческий и информативный подход!

Использование sitegototop.com для увеличения доходов. Для коммерческих сайтов увеличение трафика через sitegototop.com может привести к росту доходов. Даже если не все посетители станут клиентами, вероятность конверсий увеличивается за счет большего количества визитов. Это особенно актуально для интернет-магазинов и сайтов услуг.

Как накрутка посещений влияет на показатели сайта? Повышение посещаемости через sitegototop.com влияет на такие показатели, как число уникальных пользователей, количество просмотров страниц и среднее время, проведенное на сайте. Однако важно следить, чтобы эти метрики не выглядели искусственными, так как это может негативно сказаться на восприятии сайта поисковыми системами.

Howdy! This article couldn’t be written much better! Going through this post reminds me of my previous roommate! He always kept preaching about this. I am going to forward this post to him. Fairly certain he’s going to have a very good read. I appreciate you for sharing!

Thanks for any other wonderful article. Where else may just anyone get that type of information in such a perfect means of writing? I have a presentation subsequent week, and I am at the search for such information.

I was pretty pleased to uncover this website. I want to to thank you for ones time just for this fantastic read!! I definitely enjoyed every part of it and I have you bookmarked to see new stuff on your blog.

Я ценю фактический и информативный характер этой статьи. Она предлагает читателю возможность рассмотреть различные аспекты рассматриваемой проблемы без внушения какого-либо определенного мнения.

When someone writes an post he/she maintains the image of a user in his/her brain that how a user can know it. So that’s why this piece of writing is amazing. Thanks!

Автор явно старается сохранить нейтральность и представить множество точек зрения на данную тему.

Я восхищен глубиной исследования, которое автор провел для этой статьи. Его тщательный подход к фактам и анализу доказывает, что он настоящий эксперт в своей области. Большое спасибо за такую качественную работу!

I am regular reader, how are you everybody? This piece of writing posted at this website is in fact good.

Статья содержит актуальную информацию, которая помогает разобраться в современных тенденциях и проблемах.

Автор старается быть нейтральным, предоставляя читателям возможность самих оценить представленные доводы.

Статья содержит обоснованные аргументы, которые вызывают дальнейшую рефлексию у читателя.

I have been browsing online more than 4 hours today, yet I never found any interesting article like yours. It’s pretty worth enough for me. In my view, if all webmasters and bloggers made good content as you did, the net will be a lot more useful than ever before.

Статья содержит аргументы, подкрепленные реальными примерами и исследованиями.

Автор старается сохранить нейтральность, предоставляя обстоятельную основу для дальнейшего рассмотрения темы.

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It in fact was a amusement account it. Look advanced to far added agreeable from you! By the way, how can we communicate?

Информационная статья содержит полезный контент и представляет различные аспекты обсуждаемой темы.

Мне понравилась глубина исследования, представленная в статье.

Я хотел бы поблагодарить автора этой статьи за его основательное исследование и глубокий анализ. Он представил информацию с обширной перспективой и помог мне увидеть рассматриваемую тему с новой стороны. Очень впечатляюще!

Hi, Neat post. There’s a problem with your website in web explorer, could test this? IE nonetheless is the market leader and a huge section of folks will pass over your wonderful writing because of this problem.

We are a group of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our community. Your site provided us with valuable information to work on. You have done a formidable job and our entire community will be thankful to you.

Очень хорошо организованная статья! Автор умело структурировал информацию, что помогло мне легко следовать за ней. Я ценю его усилия в создании такого четкого и информативного материала.

Эта статья просто великолепна! Она представляет информацию в полном объеме и включает в себя практические примеры и рекомендации. Я нашел ее очень полезной и вдохновляющей. Большое спасибо автору за такую выдающуюся работу!

Автор предоставляет актуальную информацию, которая помогает читателю быть в курсе последних событий и тенденций.

Just wish to say your article is as astounding. The clarity in your post is just great and i can assume you are an expert on this subject. Well with your permission let me to grab your RSS feed to keep up to date with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please continue the rewarding work.

Hello mates, its impressive paragraph about cultureand completely explained, keep it up all the time.

whoah this weblog is wonderful i love reading your articles. Stay up the good work! You recognize, many people are searching round for this info, you can help them greatly.

Автор старается сохранить нейтральность, чтобы читатели могли основываться на объективной информации при формировании своего мнения. Это сообщение отправлено с сайта https://ru.gototop.ee/

Good day! I just want to give you a huge thumbs up for your great information you have got here on this post. I am coming back to your web site for more soon.

Thanks for some other wonderful post. The place else could anyone get that kind of information in such an ideal way of writing? I’ve a presentation subsequent week, and I’m on the search for such information.

Truly no matter if someone doesn’t understand afterward its up to other visitors that they will help, so here it happens.

Автор предлагает реалистичные решения, которые могут быть внедрены в реальной жизни.

Автор представляет разные точки зрения на проблему и оставляет читателю пространство для собственных размышлений.

Hi there, after reading this awesome piece of writing i am also delighted to share my knowledge here with mates.

Статья представляет разные стороны дискуссии, не выражая предпочтений или приоритетов.

Автор старается быть нейтральным, чтобы читатели могли самостоятельно рассмотреть различные аспекты темы.

Pretty! This was an extremely wonderful article. Thank you for providing these details.

Автор предоставляет релевантные примеры и иллюстрации, чтобы проиллюстрировать свои аргументы.

Wonderful article! This is the kind of info that should be shared around the net. Shame on the search engines for now not positioning this post upper! Come on over and consult with my web site . Thank you =)

I am truly glad to glance at this website posts which includes plenty of useful information, thanks for providing these data.

Автор приводит примеры из различных источников, что позволяет получить более полное представление о теме. Статья является нейтральным и информативным ресурсом для тех, кто интересуется данной проблематикой.

Я оцениваю объективность и непредвзятость автора в представлении информации.

After exploring a number of the articles on your website, I honestly like your technique of blogging. I book marked it to my bookmark webpage list and will be checking back in the near future. Please visit my website too and tell me what you think.

Статья представляет широкий спектр точек зрения на проблему, что способствует более глубокому пониманию.

Очень понятная и информативная статья! Автор сумел объяснить сложные понятия простым и доступным языком, что помогло мне лучше усвоить материал. Огромное спасибо за такое ясное изложение!

Автор предлагает анализ преимуществ и недостатков разных подходов к решению проблемы.

Great delivery. Great arguments. Keep up the amazing effort.

Ahaa, its good dialogue concerning this article here at this blog, I have read all that, so now me also commenting here.

An outstanding share! I’ve just forwarded this onto a coworker who was conducting a little homework on this. And he in fact ordered me dinner due to the fact that I discovered it for him… lol. So allow me to reword this…. Thank YOU for the meal!! But yeah, thanks for spending time to talk about this topic here on your web site.

Эта статья – настоящая находка! Она не только содержит обширную информацию, но и организована в простой и логичной структуре. Я благодарен автору за его усилия в создании такого интересного и полезного материала.

Статья содержит информацию, подкрепленную примерами и исследованиями.

Важно отметить объективность данной статьи.

Я оцениваю степень детализации информации в статье, которая позволяет получить полное представление о проблеме.

If some one wishes to be updated with most up-to-date technologies therefore he must be pay a visit this site and be up to date everyday.

Статья содержит сбалансированный подход к теме и учитывает различные точки зрения.

Статья основана на объективных данных и исследованиях.

Надеюсь, что эти комментарии добавят ещё больше позитива и поддержки к информационной статье! Это сообщение отправлено с сайта GoToTop.ee

I do not even know how I finished up here, however I thought this put up was good. I don’t realize who you’re however certainly you’re going to a famous blogger if you aren’t already. Cheers!

Автор статьи представляет информацию, основанную на разных источниках и экспертных мнениях.

I’m not sure where you are getting your info, but great topic. I needs to spend some time learning much more or understanding more. Thanks for great information I was looking for this info for my mission.

Автор статьи представляет различные точки зрения и факты, не выражая собственных суждений.

Статья представляет разные стороны дискуссии, не выражая предпочтений или приоритетов.

Я только что прочитал эту статью, и мне действительно понравилось, как она написана. Автор использовал простой и понятный язык, несмотря на тему, и представил информацию с большой ясностью. Очень вдохновляюще!

Hello there, You have done a fantastic job. I’ll definitely digg it and personally suggest to my friends. I’m confident they’ll be benefited from this web site.

I truly love your website.. Great colors & theme. Did you create this website yourself? Please reply back as I’m wanting to create my very own site and would like to know where you got this from or just what the theme is called. Appreciate it!

Автор статьи представляет анализ и факты в балансированном ключе.

Автор предлагает читателю дополнительные материалы для глубокого изучения темы.

Pretty nice post. I just stumbled upon your weblog and wished to say that I’ve really loved surfing around your weblog posts. After all I will be subscribing in your feed and I’m hoping you write again very soon!

Информационная статья содержит полезный контент и представляет различные аспекты обсуждаемой темы.

Статья предлагает читателям объективную информацию, подкрепленную проверенными источниками.

Автор предлагает практические рекомендации, которые могут быть полезны в реальной жизни для решения проблемы.

Я хотел бы подчеркнуть четкость и последовательность изложения в этой статье. Автор сумел объединить информацию в понятный и логичный рассказ, что помогло мне лучше усвоить материал. Очень ценная статья!

Автор предлагает объективный анализ различных решений, связанных с проблемой.

Автор статьи предоставляет информацию, основанную на различных источниках и экспертных мнениях.

Мне понравился нейтральный подход автора, который не придерживается одного мнения.

There is certainly a lot to learn about this subject. I love all the points you have made.

Я благодарен автору этой статьи за его тщательное и глубокое исследование. Он представил информацию с большой детализацией и аргументацией, что делает эту статью надежным источником знаний. Очень впечатляющая работа!

Статья предлагает читателям объективную информацию, подкрепленную проверенными источниками.

What a stuff of un-ambiguity and preserveness of valuable familiarity regarding unexpected emotions.

Я оцениваю объективность автора и его способность представить информацию без предвзятости и смещений.

Читателям предоставляется возможность оценить представленные данные и сделать собственные выводы.

It’s remarkable to visit this website and reading the views of all colleagues about this paragraph, while I am also zealous of getting know-how.

Hi! I know this is somewhat off topic but I was wondering which blog platform are you using for this site? I’m getting tired of WordPress because I’ve had issues with hackers and I’m looking at options for another platform. I would be fantastic if you could point me in the direction of a good platform.

Статья представляет анализ различных точек зрения на проблему.

Читателям предоставляется возможность ознакомиться с различными точками зрения и принять информированное решение.

Статья позволяет получить общую картину по данной теме.

Я хотел бы выразить свою благодарность автору этой статьи за исчерпывающую информацию, которую он предоставил. Я нашел ответы на многие свои вопросы и получил новые знания. Это действительно ценный ресурс!

Отличная статья! Я бы хотел отметить ясность и логичность, с которыми автор представил информацию. Это помогло мне легко понять сложные концепции. Большое спасибо за столь прекрасную работу!

Hi! I just wanted to ask if you ever have any problems with hackers? My last blog (wordpress) was hacked and I ended up losing many months of hard work due to no data backup. Do you have any solutions to stop hackers?

Информационная статья содержит полезный контент и представляет различные аспекты обсуждаемой темы.

Эта статья действительно отличная! Она предоставляет обширную информацию и очень хорошо структурирована. Я узнал много нового и интересного. Спасибо автору за такую информативную работу!

Эта статья – источник вдохновения и новых знаний! Я оцениваю уникальный подход автора и его способность представить информацию в увлекательной форме. Это действительно захватывающее чтение!

Читателям предоставляется возможность самостоятельно исследовать представленные факты и принять собственное мнение.

Thanks for your personal marvelous posting! I truly enjoyed reading it, you’re a great author.I will make sure to bookmark your blog and may come back in the future. I want to encourage you continue your great posts, have a nice evening!

Я не могу не отметить качество исследования, представленного в этой статье. Автор использовал надежные источники и предоставил нам актуальную информацию. Большое спасибо за такой надежный и информативный материал!

Heya! I just wanted to ask if you ever have any problems with hackers? My last blog (wordpress) was hacked and I ended up losing months of hard work due to no backup. Do you have any methods to protect against hackers?

Я оцениваю степень детализации информации в статье, которая позволяет получить полное представление о проблеме.

Great article.

Статья содержит анализ плюсов и минусов разных решений, связанных с проблемой.

Это помогает читателям получить полное представление о сложности и многогранности обсуждаемой темы.

Thanks , I have recently been searching for info approximately this topic for ages and yours is the best I have found out so far. But, what in regards to the bottom line? Are you certain concerning the supply?

Автор представляет различные точки зрения на проблему без предвзятости.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on meta_keyword. Regards

Я оцениваю аккуратность и точность фактов, представленных в статье.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts about meta_keyword. Regards

Yes! Finally someone writes about keyword1.

I’m gone to inform my little brother, that he should also pay a visit this website on regular basis to take updated from most up-to-date news.

This is a topic which is close to my heart… Take care! Where are your contact details though?

Автор предлагает анализ различных точек зрения на проблему без призыва к одной конкретной позиции.

Автор предлагает аргументы, подтвержденные достоверными источниками, чтобы убедить читателя в своих утверждениях.

Excellent weblog here! Additionally your website a lot up very fast! What host are you using? Can I get your associate hyperlink to your host? I want my web site loaded up as fast as yours lol

Я нашел в статье несколько полезных советов.

Я восхищен этой статьей! Она не только предоставляет информацию, но и вызывает у меня эмоциональный отклик. Автор умело передал свою страсть и вдохновение, что делает эту статью поистине превосходной.

I go to see everyday a few web pages and websites to read articles, but this webpage provides feature based content.

Приятно видеть, что автор не делает однозначных выводов, а предоставляет читателям возможность самостоятельно анализировать представленные факты.

Хорошо, что автор статьи предоставляет информацию без сильной эмоциональной окраски.

Автор предлагает анализ плюсов и минусов разных подходов к решению проблемы.

Hi, after reading this awesome article i am as well happy to share my knowledge here with friends.

Эта статья является настоящим источником вдохновения и мотивации. Она не только предоставляет информацию, но и стимулирует к дальнейшему изучению темы. Большое спасибо автору за его старания в создании такого мотивирующего контента!

Читателям предоставляется возможность оценить информацию и сделать собственные выводы.

Статья содержит актуальную статистику, что помогает оценить масштаб проблемы.

I am sure this piece of writing has touched all the internet users, its really really pleasant piece of writing on building up new blog.

Я бы хотел отметить актуальность и релевантность этой статьи. Автор предоставил нам свежую и интересную информацию, которая помогает понять современные тенденции и развитие в данной области. Большое спасибо за такой информативный материал!

It’s very trouble-free to find out any matter on web as compared to books, as I found this paragraph at this web page.

Статья содержит аналитический подход к проблеме и представляет разнообразные точки зрения.

Я восхищен тем, как автор умело объясняет сложные концепции. Он сумел сделать информацию доступной и интересной для широкой аудитории. Это действительно заслуживает похвалы!

If you desire to improve your experience just keep visiting this web site and be updated with the most up-to-date gossip posted here.

Радует объективность статьи, автор старается представить информацию без сильной эмоциональной окраски.

Статья предоставляет разнообразные исследования и мнения экспертов, обеспечивая читателей нейтральной информацией для дальнейшего рассмотрения темы.

This is really interesting, You’re a very skilled blogger. I’ve joined your rss feed and look forward to seeking more of your wonderful post. Also, I have shared your website in my social networks!

Автор предлагает анализ преимуществ и недостатков различных решений, связанных с темой.

My spouse and I absolutely love your blog and find a lot of your post’s to be just what I’m looking for. Do you offer guest writers to write content for yourself? I wouldn’t mind producing a post or elaborating on most of the subjects you write concerning here. Again, awesome weblog!

Это позволяет читателям формировать свою собственную точку зрения на основе фактов.

I think the admin of this website is actually working hard in support of his web page, because here every data is quality based data.

Hola! I’ve been following your website for some time now and finally got the courage to go ahead and give you a shout out from Lubbock Tx! Just wanted to say keep up the good job!

Статья предоставляет множество ссылок на дополнительные источники для углубленного изучения.

Автор статьи хорошо структурировал информацию и представил ее в понятной форме.

Я чувствую, что эта статья является настоящим источником вдохновения. Она предлагает новые идеи и вызывает желание узнать больше. Большое спасибо автору за его творческий и информативный подход!

Я прочитал эту статью с большим удовольствием! Автор умело смешал факты и личные наблюдения, что придало ей уникальный характер. Я узнал много интересного и наслаждался каждым абзацем. Браво!

Wow, marvelous weblog layout! How long have you ever been running a blog for? you made running a blog glance easy. The whole glance of your web site is great, as well as the content material!

Читателям предоставляется возможность обдумать и обсудить представленные факты и аргументы.

Undeniably believe that which you stated. Your favorite reason appeared to be on the net the simplest thing to be aware of. I say to you, I definitely get irked while people think about worries that they plainly don’t know about. You managed to hit the nail upon the top as well as defined out the whole thing without having side-effects , people could take a signal. Will probably be back to get more. Thanks

Heya! I’m at work browsing your blog from my new iphone! Just wanted to say I love reading your blog and look forward to all your posts! Carry on the outstanding work!

I was recommended this blog by my cousin. I am not sure whether this post is written by him as nobody else know such detailed about my trouble. You are wonderful! Thanks!

Автор предлагает практические советы, которые читатели могут использовать в своей повседневной жизни.

Автор предлагает читателю дополнительные материалы для глубокого изучения темы.

Автор старается сохранить нейтральность и обеспечить читателей информацией для самостоятельного принятия решений.

Статья представляет интересный взгляд на данную тему и содержит ряд полезной информации. Понравилась аккуратная структура и логическое построение аргументов.

Автор статьи представляет информацию, основанную на достоверных источниках.

Hello there, simply became alert to your blog thru Google, and found that it’s truly informative. I’m going to be careful for brussels. I will be grateful should you proceed this in future. Many folks will likely be benefited out of your writing. Cheers!

Автор предоставляет анализ последствий проблемы и возможных путей ее решения.

I do not know if it’s just me or if perhaps everybody else encountering issues with your website. It seems like some of the text in your posts are running off the screen. Can someone else please comment and let me know if this is happening to them too? This might be a problem with my browser because I’ve had this happen before. Many thanks

Heya! I just wanted to ask if you ever have any trouble with hackers? My last blog (wordpress) was hacked and I ended up losing several weeks of hard work due to no back up. Do you have any methods to prevent hackers?

Информационная статья основывается на исследованиях и надежных источниках.

I was wondering if you ever considered changing the page layout of your blog? Its very well written; I love what youve got to say. But maybe you could a little more in the way of content so people could connect with it better. Youve got an awful lot of text for only having one or two pictures. Maybe you could space it out better?

Автор предоставляет различные точки зрения и аргументы, что помогает читателю получить полную картину проблемы.

Hi! I could have sworn I’ve visited this blog before but after looking at a few of the posts I realized it’s new to me. Anyhow, I’m certainly delighted I came across it and I’ll be bookmarking it and checking back often!

Heya i am for the first time here. I came across this board and I find It really useful & it helped me out much. I hope to give something back and aid others like you helped me.

It’s truly very complex in this active life to listen news on TV, so I simply use the web for that purpose, and take the newest information.

Статья помогла мне получить новые знания и пересмотреть свое представление о проблеме.

Мне понравился стиль изложения в статье, который делает ее легко читаемой и понятной.

I always emailed this weblog post page to all my associates, because if like to read it then my contacts will too.

I every time spent my half an hour to read this blog’s content all the time along with a mug of coffee.

Статья содержит обширный объем информации, которая подкреплена соответствующими доказательствами.

Статья предоставляет полезную информацию, основанную на обширном исследовании.

Статья представляет разнообразные аргументы и позиции, основанные на существующих данных и экспертном мнении.

Статья представляет все основные аспекты темы, без излишней детализации.

I’m not that much of a internet reader to be honest but your blogs really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your website to come back later on. Many thanks

We absolutely love your blog and find a lot of your post’s to be just what I’m looking for. can you offer guest writers to write content in your case? I wouldn’t mind publishing a post or elaborating on a few of the subjects you write about here. Again, awesome web site!

You’re so awesome! I do not suppose I’ve truly read through a single thing like this before. So great to discover somebody with original thoughts on this topic. Seriously.. many thanks for starting this up. This web site is one thing that is required on the internet, someone with a little originality!

Автор статьи хорошо структурировал информацию и представил ее в понятной форме.

Автор не высказывает собственных предпочтений, что позволяет читателям самостоятельно сформировать свое мнение.

Автор предлагает анализ плюсов и минусов разных подходов к решению проблемы.

Автор предлагает реалистичные решения, которые могут быть внедрены в реальной жизни.

Hello there, just became alert to your blog through Google, and found that it’s really informative. I’m going to watch out for brussels. I will appreciate if you continue this in future. A lot of people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

Автор предлагает анализ разных подходов к решению проблемы и их возможных последствий.

Greetings! Very helpful advice within this post! It’s the little changes which will make the biggest changes. Thanks a lot for sharing!

Я хотел бы выразить свою благодарность автору этой статьи за исчерпывающую информацию, которую он предоставил. Я нашел ответы на многие свои вопросы и получил новые знания. Это действительно ценный ресурс!

Статья помогает читателю получить полное представление о проблеме, рассматривая ее с разных сторон.

Its like you learn my thoughts! You seem to understand so much about this, like you wrote the book in it or something. I feel that you just can do with some p.c. to drive the message house a bit, but instead of that, that is fantastic blog. A fantastic read. I will certainly be back.

Как работает sitegototop.com? Sitegototop.com использует специальные технологии и сети, чтобы генерировать искусственный трафик на сайт. Это могут быть как автоматические посетители, так и реальные пользователи, привлеченные через рекламные сети. В зависимости от пакета услуг, клиенты могут выбирать количество посещений, географию посетителей и их действия на сайте. Это дает возможность точно настроить трафик под конкретные задачи.