It is my firm conviction that the legacy of the blues has largely been shaped by the standards of the white market entrepreneurial spirit. When we think of pre-war blues we tend to see a lonely, black hobo with a guitar in his hand. Indeed, many a blues player from the twenties and the thirties corresponds to this iconic image, but is this not largely stemming from the fact that record companies in the twenties noticed that there was a market for this kind of music ? Is it then all that surprising that many songsters and musicians narrowed their repertoire to get the attention of those white entrepreneurs to get them recorded and earn an extra dime in this way?

In order to have a full picture of how blues evolved, we have to bear this thought in the back of our mind, and we also have constantly to be aware of the human tendency to oversimplify our view of the past. In looking through the fog of times gone by, we tend to loose our sight of the details, or we tend to see only the broad silhouettes without paying attention to the texture and details of the past which we need to grasp to fully understand what really happened.

I want to highlight two texture elements in this blog post :

– early blues and pre-blues were not a pure black business;

– in this early blues, the guitar was not the prime instrument;

In order to see this historical texture, I want to make a very deep dive into history, and more particularly into the emergence of the Mississippi region and its socio-economic evolution. It may seem odd to do this, but at least for me, it explained a lot of the way the Mississippi soil proved out to be very fertile not only for cotton but also for this unique musical style that in its origin was not exclusively black.

The Mississippi emerged as an important region between 1798 and 1820, when its population grew from a mere 9.000 to more than 220.000. It was the promised land for adventurers. The prices of traditional crops on the East Coast (a.o. tobacco and corn) were falling, whilst at the same time the demand in Europe (France, Great Britain, …) pushed up the world price of cotton. The invention of an efficient way to separate the seed and the fiber of the cotton (cotton engine, or short : cotton gin) in 1793 was more than a coincidence. Cotton became the dominant crop in the Southern region, which was a major source of wealth for a white population in the South, that drove away the Indians from their land and imported slaves to do the hard field work in the blistering sun. Cotton was king and created a white elite, both economically and politically.

As the prices of both land and slaves rose due to the high demand, the social split between the haves and the have-nots got bigger and bigger. Small, white farmers who couldn’t keep up with the pace of the rising prices for land and slaves were driven to less fertile soils, where no cotton could be cultivated. They were cut off from the main source of wealth and were not much better off than the black slaves working on the plantations of the happy few.

In this context it is easy to see that the Civil War (1864/65) was essentially all about trying to maintain the rigid social divisions in the South, and to maintain the wealth of the Southern plantation owners based on land and slaves. Northern States proclaimed the free trade of labour (white & black) in a context of industrialization.

The Civil War was devastating for the South. The losses of the South were catastrophic, for both the white and the black population. Cotton exploitation came to a standstill, men were sent to the army but never came back. It left the South in a state of complete social, economic, human and financial chaos. The death rate was disastrous.

The big question after the war was of course : how to get the economy running again ? The slaves had been freed (“freedmen“) and many left the plantations that had chained them all those years. But how to reconstruct a region which first source of wealth was labor and soil? The liberal north proposed a policy of “40 acres and a mule” : the “freedmen” would get their fair share of land and a mule to get the crops growing again (the army didn’t need the mules anymore anyhow). This policy didn’t work out however. The white landowners didn’t like the idea very much of their former slaves getting a piece of their cake (land). At the same time, the black population was not really ready to start as independent entrepreneurs managing their own piece of land and entering into an economy of which they had only been the passive element, not an active component.

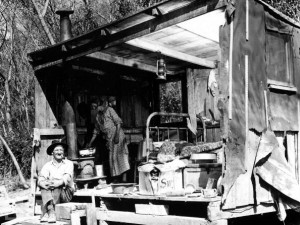

Contractual labour, as was the case in the industry of the north, didn’t seem to be an option either. It requires the availability of cash, and cash was lacking everywhere in the South. The only elements to restart the economic engine again were land and labour. It is thus not too surprising that a system of tenants and sharecroppers was the answer. The system of tenants and sharecroppers developed in very different gradations in the different regions of the South. They had though one thing in common : there was again a division between the haves and the have-nots. The latter either paid to rent the land they were allowed to cultivate, or they had to share a part of their crop with the landowner who sold it on the market. The landowner provided for the housing, food and clothing, which cost was deducted from the price he got from selling part of the harvest. You guess right : the sharecropper being illiterate and not able to keep detailed accounts was constantly the victim of this system. He was duped again and again. When the value of the crop he ‘shared’ was not sufficient to cover the cost of living, it only added to his debts towards the landowner. He was formally no longer a slave, but was now bound to the land by a severe credit system. To make things only worse, the landowner started to allow furnishing merchants to provide his sharecroppers and tenants with food and clothing. The merchants were not paid in cash but made their final accounts when the crop was harvested. Precisely : the price they got didn’t cover the expenses and the system of perpetual debts was confirmed.

The have-nots were thus chained to both clever merchants and greedy landowners in an endless cycle of debts and landlessness. There was nothing new under the sun.

This system condemned them to suffer from living conditions which were much worse than that of people in the Medieval Europe, sleeping and living in wooden shacks without windows, and lacking any form of sanitation or water supply. Families of ten and more children were no exception.

It is crucial to see all this in a context in which the world prices of cotton started a steady decline since 1870.

The line dividing the haves and have-nots did however not run in parallel to the line between white and black. The social cleavage ran across the racial division. The lines of power and wealth ran across the racial lines. A very large proportion of the white population had been particularly hard struck by the Civil War which had claimed the lives of many fathers and sons. The financial debts of the small white farmers who didn’t have any slaves were enormous.

The system of sharecroppers and tenants was far from being an exclusive black phenomenon. In Georgia for instance, half of the tenant land was white. In some regions, the number of white sharecroppers outnumbered the number of black sharecroppers. An economic study based on early 20th century census data showed that black and white sharecroppers were paid equally (Competition and the Compensation of Sharecroppers by Race: A View from Plantations in the Early Twentieth Century1 – Lee J. Alston University of Illinois and Kyle D. Kauffman – Wellesley College and W.E.B. DuBois Institute, Harvard University). It was not uncommon to see black and white work on the same field.

The social structure of the South changed even more when the mechanization made its way to the cotton agriculture triggering one of the biggest migration flows ever seen in human history : black leaving the South to look for paradise in the Northern industrial cities. Fed up with the Jim Crow laws and confronted with the economic losses due to the spread of the cotton pest (boll weevil – subject of so many blues songs), the blacks left their shacks in the South to trade them for a place in the ghetto’s in the North. This made the impoverished classes of the South more and more white. The disastrous great flood of the Mississippi delta in 1927 (comparable to the Katrina catastrophe in 2005) and the drought years that started in 1930 only added extra migration pressure.

It is in this context that we need to listen to the pre-blues and its transformation into the blues of the twenties and thirties.

In an interview given by one of the great delta blues historians, Gayle Dean Wardlow repeatedly stresses that though the Southern States were a segregated society where the black were clearly at the bottom of the social structure, musically black and white were not totally segregated to the same extend that they were in the larger society. Black and white crossed the boundaries and played with each other; white and black intermingled in their music. Music was an essential part of the entertainment in a society that lacked the spread of records and radio. Live music was all there was. Both black and white had descended from the hill country to the Mississippi delta because of the poor living conditions in the hill country; the Mississippi delta was the best place to go and work. The earnings in the Mississippi delta could be as much as three or four times higher than the ones in the hill country sides.

The music played was dance music, music for entertainment for both black and white and the repertoire of this entertainment music drew from a common pool of music of which it was sometimes hard to say whether it was white or black. Very often, the black musicians’ music sounded white. Charters describes it lively how people gathered together under trees and would “dance until their faces shine with sweat and the party is shouting and clapping encouragement to keep the musicians working over their instruments” (The Country Blues, page 224). Music was traded between white and colored people and it was often impossible to tell which song was written by whom, black or white.

Jimmy Rodgers, the first big (hillbilly) (white) country star recorded several blues songs. And he was not alone. Dock Boggs, an influential (white) old-time singer, songwriter and banjo player tells the story about him when he was young and was following an African-American guitarist in the streets to learn how to play, and how he would sneak out to places where he could hear the black string bands play. Boggs’ music is said to be a mix of white folk and African American blues.

At the same time, some black musicians made their name in the blues only by accident and because it best helped them make a living out of it. This was the case for Lonnie Johnson, who started out learning piano, violin and guitar but won a blues contest in 1925 and was subsequently targeted as a blues artist, while he admitted that he would have played any style to get recorded. Much of his later music also tends more to be jazz than blues.

The instruments played by this older generation was not (exclusively) guitar. The fiddle was a a very popular instrument that was played in combination with the banjo. A typical European instrument, the fiddle, (brought by the Scottish and Irish immigrants) was harmonized with an African instrument in the string bands which occupied the scene in the pre-blues period. The african banjo was brought to America by the slaves and was paired with the fiddle to produce a very lively form of entertainment and dance music. The earliest mentions of this combination go back to the late 18th century.

This early folk music thus combined elements of African tradition, techniques tunes and songs with Irish-Scottish violin music producing music that often can be compared to square dances.

Gradually, when blues became more and more popular in the years after 1910, and especially after 1920, these string bands started incorporating more and more blues songs in their repertoire, or even to re-label existing songs with the sticker : blues. A very popular string band which became very influential in the 30ties were the Mississippi Sheiks (named after a role played by Rudolf Valentino), who played for both black and white.

In the past few days, I started listening to some of that old string band music, and I have to say that at times I had to have a very close look at the album cover to see whether the artists were black or white ! The difference between “white” country folk and “black” blues was hard to make.

But after all, was it not only, after several studio sessions in 1954, when Elvis Presley started playing in his own way Arthur ‘Big Boy’ Crudup’s ‘That’s allright mama‘, that the fire of his success was ignited? It was only when this white boy started playing the “black” blues that the doors of stardom opened for him. Blues re-entered the mainstream in the 50ties through the white youngsters.

But this is just an illustration of the fact that it would be a big mistake to see music as either white or black, precisely the pointed that I have tried to make in this post.

I greatly appreciate all the info I’ve read here. I will spread the word about your blog to other people. Cheers.

Zeer leuk om te lezen dat gewone mensen geen onderscheid maakten tussen rassen, maar elkaar aanvulden en aanzetten tot nieuwe klanken. Wat een immense rijkdom is daar niet verloren gegaan?

zoals altijd, uitkijkend naar nog meer van deze wetenswaardigheden!

mamamiezemuisje