Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Willem van Dullemen, who in his passion for folk (music) helped me in getting at my disposal part of the reading material. I also owe a great deal to watching the documentary “Free Show Tonight” produced, in 1983, by Paul Wagner, Steven J. Zeitlin, and Barr Weissman. It is a unique Folkstreams document which brings the oral history of the old-time travelling medicine show performers, with a recreated medicine show staged in a small North Carolina town. I highly recommend it.

Folkstreams founder Tom Davenport also directed “Born for hard luck”, brushing in 1976 the biography of Peg Leg Sam Jackson. The footage includes excerpts from one of Jackson’s last medicine shows, videotaped at a county fair in 1972, and material filmed near his home in South Carolina in 1975.

_________________________________________________

President Theodore Roosevelt once called the Chautauqua “the most American thing in America.” At the latter part of the nineteenth and early decades of the twentieth century, the Chautauqua was one of the most popular shows in rural America. Though ordinarily billed as “high culture”, with an emphasis on education and lecture, it provided entertainment and culture for the whole community, featuring speakers, teachers, musicians, entertainers, preachers and “specialists” of the day. The music was a major ingredient, mainly consisting of band performances, often seasoned with spirituals, performed by such groups as the Jubilee Singers. Ballads and ‘old country’ tunes were also part of the repertory. The show reached otherwise socially and geographically isolated farming communities.

I doubt whether Roosevelt labeled the Chautauqua rightly the “Most American thing in American”, if we compare it to the other contemporaneous popular traveling show: the Medicine Show. Obviously, as a non-American, I have little or no credentials for qualifying or disqualifying something as typical or “most” American. Yet, despite its European origins, I am convinced that the Medicine Show featured sufficient characteristics that eventually made it a core element of the American culture, to a much higher extent than the Chautauqua shows. Disputing Roosevelt’s statement is however not my objective. Let me, in what follows, indulge in briefly demonstrating how the Medicine Show contributed to shaping American entertainment, how it was a cardinal channel for the dissemination of popular music, including the blues, and how it was for many songsters and musicians a most important professional opportunity.

Before jumping into the story, it might be useful, especially if your native tongue is not English, to point you to the small glossary at the bottom of the article, where some expressions of the Medicine Show business vocabulary are summarized.

Now, follow me on the amazing journey of the American Medicine Show.

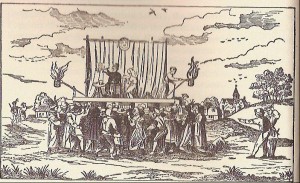

THE CHARLATAN CROSSES THE ATLANTIC

The story starts in Europe, as early as the fourteenth century, with traveling charlatans putting on performances to promote their curing products and services. “Doctors” “mounted the bench” (hence, the name: mountebank) , a stage, table or box, at fairs, street corners, in market squares or wherever they could find an audience, to convince the crowd of its desperate need for his medical miracle cures. To draw the largest crowd and to keep its attention fixed as long as possible, the mountebanks resorted to a wide variety of entertainment including, among others, jugglers, musicians, magicians, and clowns. Small scale spectacles alternated with their lectures that demonstrated how their tonics and services would surely cure any ailment his spectator had, whether he was aware of it or not. Extant documents describe such scenes in Venice in 1608, and in 1618 in Paris, where a famous mountebank’s performances are said to have inspired the work of Molière.

In England, some nostrum makers succeeded in obtaining “Royal Patents” for their curing tonics and elixirs, a practice which eventually introduced the term ‘patent medicines’ for all their products, whether they were “formally” patented or not.

The mountebanks crossed the Atlantic Ocean, and quickly spread in America to such a degree that by the end of the 18th century, some states felt it necessary to pass legislation outlawing the mountebanks arguing that their deceitful practices corrupted manners, promoted idleness, and were a threat to good order and religion (McNamara, 1995). The prohibitive legislation did, however, not stop the delights brought to the crowds, which remained eager for the entertainment and exotic show performed by a man who, on top, promised to cure all their ailments.

HEALY HEALS

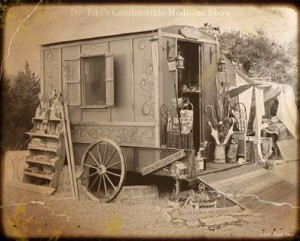

Before the 1850’s, the American Medicine Show largely kept its European features, based mainly on the oration skills of a solo salesman. Medicine Shows were the operation of one man who traveled from town to town, on a wagon with a small platform on the back. Gradually, however, the show integrated elements from local entertainment forms, borrowing for instance from the minstrel shows the banjo and the black face idiom. It was the start of the Americanization.

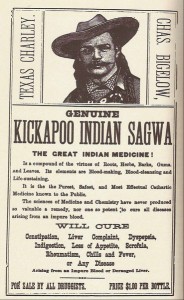

After the Civil War, the show continued to drift away from its European origin when the patent medicine industry began to take a hold of the medical field. Like the American circus flourished as the product of (white) business entrepreneurs, so did the grasp of the new industrial power of patent medicine definitely change the face of American Medicine Show. The show business technique became a crucial ingredient of an act that was set up to sell products, and to generate profits for big companies which had their headquarters, far away from the remote corners where once the quacks used to produce their tonics in the bathtubs of their dirty, small town hotel rooms. Following P.T. Barnum who linked popular entertainment to the sole cause of profit making based on the curiosity and naivety of the mass, two keen business men by the name of John E. Healy (what’s in a name?) and Charles F. Bigelow, kicked off their “Kickapoo Indian Medicine Show” in the early 1880’s.

Entertainment and performance were now the instruments destined to suit the needs of medicine companies, which used the mountebanks, in addition to catalogs and newspaper advertisements to bring their brand to the crowd. The Medieval charlatan was transformed to a sales representative, but one of a special kind who mastered the art of spieling, framed in a carefully staged professional show that was to trick people to buy the products that were supposedly to cure. To this effect, the concept of a global show, borrowing from all the contemporary popular forms of entertainment, was developed. The small wagon of the lone ‘doc’ was replaced by a caravan of wagons of which the magnitude varied from a small group of entertainers, singers, dancers, acrobats, comedians and actors, to a fully-fledged show, including a brass band. They drew their inspiration from circuses, Wild West shows, minstrel shows, and from whatever that was popular at the moment and attracted the crowds from a city to the smallest corners of the country side.

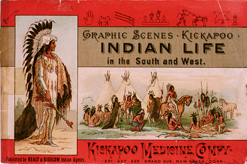

Keen entrepreneurship also inspired these men to season the shows with an air of mysticism. The efficacy of the medicines was “demonstrated” by tying them up with the image of the mystic power of Native American herbs and remedies, or with the scent of the secret knowledge hidden in Oriental miracle cures. The Kickapoo Medicine Company shows, set up by Healy and Bigelow in the early 80’s, featured as one of the best-known of the Indian shows. Operating from New York, and later from New Haven, Connecticut, these two managers decided to sell their patented tonics and salves, using Medicine Shows which employed Indians, supposedly Kickapoo’s. The mysticism of Native American skills served as an aura for the marketing of their medicine brands. Not only did the latter carry the speaking names of “Sagwa”, “Indian Oil” or “Kickapoo Salve”, the show used fake Indian stage characters, and the wooden stage platform was surrounded with wigwams. The concept proved extremely successful to draw in the crowds: it was widely copied, leading in the latter 19th century to more than seventy-five touring companies of the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Shows. There was a widespread belief that the Indian, by his intimate connection to nature, had learned to understand the secrets of natural medicine, and had acquired a huge medical wisdom.

Next to the Native American tribal element, another theme elaborated by the Medicine Shows was the mystic knowledge of the Asian, or the morality and honesty of the Quaker. Honesty was however not the true character of the mountebank: no more than the Indian of the Kickapoo Show, was the Chinese man of the Oriental show an actual Asian, or was the preacher of the Quaker Medicine Show a real Quaker. The personae on the platform of the Medicine Show were stereotyped characters. Even the pitch man himself, often called ‘doctor’ or ‘professor’, was as a cliché, wearing a wide brimmed hat, dressed up in fancy clothes, and with long hair curling over his shoulders. The characters and their attire changed moreover, depending on whether the performance took place in for instance a Western or Eastern state.

AMERICANITIS

Obviously, the success of the Medicine Show in the 19th, and for a part in the early 20th century can be explained by global cultural and socio-psychological features which make the combination of entertainment and marketing, for whatever product, highly efficient. The early European charlatan already used show elements to merchandise his services. The flamboyant dentist, Edgar “Painless” Parker, who in the late 19th century started his career as a street dentist in New York, later managing a combination of traveling circus/dental clinic, understood all too well how to promote his “painless dentistry” services when he wrapped them in publicity stunts such as doing dental work on a hippopotamus. It is largely the same technique which today for instance pins the strategy of the infomercials, and which inspires the pop ups when we surf the internet.

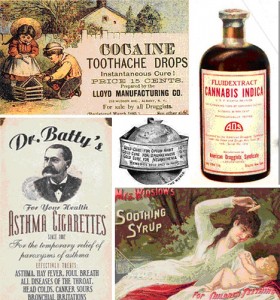

Yet, when evaluating the Medicine Shows, we furthermore need to take into account the particular historical context of the 19th century Western culture. There existed a firm belief that science was the ultimate instrument that enabled mankind to conquer nature. A medicine doctor carried a high esteem, borrowed from this growing belief in the power of knowledge. More than ever before, his products and services were believed to be the answer to human pain and suffering. By today’s standards, these practices and remedies are obviously “fantastic” and extravagant. Drugs that contain opium are no longer used to quiet down children, and we no longer consider Dr. Batty’s cigarettes helpful for soothing asthma, or give our teething children cocaine drops. If anything, there was no limit to the fantasy and creativity of the 19th century “doctors” to propose cure-all tonics and drugs for physical and psychic disorders which were defined in such a general way as to cover almost everything. There was, yet, no reason why people would question whatever the doctor proposed. Unsurprisingly, this opened the gates for keen entrepreneurs to spread their products wrapped up in most attractive, free and exotic entertainment, which was often the most important annual event in the life of a farming or small town community. The absence of any central drug regulation made it only easier.

Additionally, the social and economic changes in America after the Civil War, and especially in the latter part of the 19th century were massive. On the one hand, science promised a better future that was under human control; on the other hand, there was also great uncertainty triggered by the upheaval of traditional structures and roles. The industrialization and modernization progressed at a very quick pace causing in large parts of the population unrest regarding their future position in American society. This unrest helps to explain the rise of the populist movement in the last decade of the century, as a spokesman of mostly poor white cotton farmers in the South and wheat farmers in the plains States who feared suppression by bank, railroads and economic elites. The aforementioned Chautauqua movement can partly be depicted from the perspective of this populist concern. At the same time, middle class America reacted through a Progressive Reform movement to counter act the spread of corruption by the new political and economic machinery that prospered on the modernization. In any case, the stability of social roles and identities was shaken, and the swift changes also induced anxiety and frustration, and probably surpassed many people’s psychological capacities to handle and integrate the change in their daily lives.

It is no coincidence that in 1869 George Miller Beard coined for the first time the term “neurasthenia” to denote a psycho-pathological condition with symptoms of fatigue, anxiety, headache, neuralgia and depressed mood. The neurologist believed that “neurasthenia”, an exhaustion of energy of the central nervous system, had its roots in the modern civilization. Americans were said to be particularly prone to the condition, resulting in the nickname “Americanitis”. The Rexall Drug Company capitalized on the “epidemic” by hawking its miracle cure tonic called “Americanitis Elixir.”

This was the context in which the American medicine industry blossomed. It is striking how the American newspapers of these times were rife with advertisements for medicines and miracle-cures, though mostly harmless, but many containing generous quantities of ingredients of alcohol, opium or cocaine which upon first use surely made the patient feel better, but at the long run caused more harm than the initial ailment. As an illustration, I randomly dived into a digitized newspaper archive and stumbled across the Davenport Gazette published March 20th 1887 which contained at its second page the speaking advertisement by the Ely Brothers, Druggist, N.Y. :

“Ely’s cream balm cures cold in head, catarrh, rose-cold, deafness, and headache. Cream balm is not a liquid, snuff or powder. No injurious drugs. No offensive odor. Applied into cach nostril is quickly absorbed. A quick relief. A positive cure.”

The miracle balm was charged 50 cents at the druggist, 60 cents when ordered by mail (as a comparison: the journal sold at 5 cents) (see illustration).

Hence, the popularity of the Medicine Shows was certainly fueled by the general climate in which the population, probably feeling a general ‘malaise’, was also eager to dispose of simple all-cure medicines. For the drug companies, these traveling shows proved to be a very efficient way to disseminate their products, more efficient probably than the myriad of newspaper and magazine advertisements. Advertising for mail-order business was lucrative, but nothing could beat the Medicine Show. Not surprisingly, the companies used the Medicine Shows also to distribute, after a show, paperback booklets containing the songs, and more importantly, the name and the list of all the ailments their medicinal products could cure. Long after the ‘doc’ and his group had left town, the songbooks and ads left a tangible trace. It was moreover not unusual that the ‘doc’ convinced the local drug store to buy enough of his bottles and salves to keep the offer going on until his return, a year or so later.

THE MEDICINE SHOW THRILLED TO DEATH

“When the show came to town, one could hear the music already a mile away”, narrates a lady who enjoyed the entertainment when she was a young girl (Documentary Footage: Free Show Tonight, 1983). “And”, she continued, “it just thrilled us to death and gave us the greatest desire to go to some of the shows. And it was something that we didn’t have often. It came maybe once a year, and the following year, when people began to have the crops they had a little money. So that’s when the shows came.”

The arrival of a Medicine Show was a big, happy event, wherever it went, all over the nation. As another contemporary observer put it: “The medicine show was the one breath of romance, the one touch of lands across the sea that invaded the isolation of our remote little town.” (Thomas Leblanc, in: A. Dargan, 1983). The doctor was a world traveler who brought to town both entertainment and the promise of a good and healthy long life.

As already mentioned, the size of the traveling company varied, and was often limited to a few acts, with a pitch doctor using a soap box at the street corner to hawk his nostrums. These were the low pitch shows. A standard show company however, occupied a free lot at the town border, and might include a lecturer-manager, a group of sketch players, a singer and dancer, a piano man and a blackface comedian. Some staged also a vocal quartet, contortionist, a trapeze performer, a magician, sword swallower or a juggler. These were the high pitch shows, of which some reportedly had mobile units with an integrated parlor organ. Just like circuses, some used animals, such as snakes or monkeys, to perform their acts. The geek biting off the head of a snake, or of a chicken, was a regular attraction, and though the geek did not every night perform his biting act, the expectation that he might was enough to draw the crowds.

The shows, performed in the (late) evening, might last two hours or more, and could comprise up to ten different acts, alternated with the lectures and pitching of the doctor. The show was carefully prepared and arranged to bring and keep the audience in the perfect mood to sell as much possible. Comedy and humor, of the kind understandable for the ‘country folk’, were the key ingredients of a successful promotion.

It was a highly professional matter, and, not to forget, very hard work. The crowd needed to be captured, tricked and constantly scanned to see whether it stayed correctly tuned to a buying mood. The doctor needed to persuade his audience that they had the diseases and ailments for which he happened to have the correct remedy. He had to be able to sell ice to the Eskimos (Olsson, 1977). In a very short time span he had to instill, in cooperation with his group of performers, confidence, create a desire, and close the sale. “Faced with these obstacles, the pitchman’s presentation had to be of sterling quality, rendered with the golden tongue of oratory” (The Vi-Ton-Ka Medicine show program book, 1983).

Versatility and resourcefulness were indispensable. The artists were also the roadies, who were expected to take care of the publicity announcing the show in advance, and commonly had to be able to play different roles as varied as ventriloquism, blackface comedy and magic. The more instruments a performer could play the better. As a show might stay in one location sometimes from one to two weeks, a change of bills every night was a must. Hence, the size of the repertoire had to be enormous, and flexible too to suit the needs of the different audiences in very different regions.

The public was racially mixed, but, Jim Crow was just around the corner. Anna Noell, who in the twenties and thirties as a young lady performed on Medicine Shows with her husband and their “boxing and wrestling chimpanzees”, narrates how they were performing in North Caroline “back in the days when you had to have a chain down in the middle of your lot so the white folks could be on one side and the black folks on the other side.” (Documentary Footage, Free Show Tonight, 1983).

The blackface character, borrowed from the Minstrel Shows, was a dominating one in most Medicine Show performances. Playing the archetype of Sambo or Jake, dressed with oversized shoes and pants, and a gaudy colorful outfit, he might serve simultaneously as the producer, the chief comedian, the master of ceremonies, and he was often the one who introduced the specialty acts. He was expected to know all the traditional material of the minstrel shows. The blackface role was either played by an African-American (his face painted in black), or by a white performer. It is noteworthy, that the heydays of the Medicine Show paralleled the rising popularity of the coon songs which depicted the black in the most grotesque and racist way.

NOSTRUMS AND QUACKERY: THE GREAT AMERICAN FRAUD

The turn of the century was also the turn of the page for the Medicine Shows, in two respects. First: as the nature of the folk entertainment that inspired the material of the Medicine Show changed, so did the latter turn away more and more from its classic exotic show elements and minstrelsy, to integrate vaudeville acts. Second: as a result of a series of social changes, the popularity of the Medicine Shows significantly declined.

The popular entertainment increasingly embracing the vaudeville theater and its variety acts, the Indian, Oriental and Quaker shows lost their attraction and began to look ‘old fashioned’. Yet, even if the Medicine Shows gradually shifted more and more to vaudeville acts, they maintained their unique character, and were more than just a vaudeville show garnished with commercial pitching and hawking. In their utterly direct contact with the public, they kept offering a particular mixture of vaudeville, minstrelsy, burlesque theater, and dance. The shows maintained their very own street theater style that, throughout the country, provided fun and entertainment for the large crowds. The sale of the medicine product remained a core business, and the entertainment was after all primarily an extended bally to draw the customers and to eventually persuade them to exchange a dollar for a miracle bottle.

A myriad of circumstances worked against the continuation of the popularity of the Medicine Shows. Obviously, the (black and white) vaudeville theater itself was more and more a serious competitor for the entertainment hunger of the public, which, on top, found a new fascinating medium in the movie theater. Let us not forget that by 1912, there were already a number of major film companies which operated from the West Coast.

Parallel with the growing public doubts on the efficiency of the medicines pitched by the “show doctors”, legislation on production, branding and commercialization of drugs made it increasingly difficult to come up with tonics often directly tapped from a bathtub mixture of innocent and less innocent ingredients. The passage, on 30 June 1906, of the “Pure Food & Drug Act” rendered it for pitch men harder to keep their business running as usual, even if the Act initially only aimed at ensuring that certain special drugs, including alcohol, cocaine, heroin, morphine, and cannabis, be accurately labeled with contents and dosage. Legislation in later years however also targeted the prohibition of products if they were not considered safe, followed still later by efforts to outlaw products which were safe but not effective.

This increasingly restrictive legislation forced some to disband the show, and to concentrate solely on the sale through a central drug store or through mail orders, or, if they wanted to stay on the road, to step down the ladder from high to low pitch. Fewer bottles sold, fewer dollars cashed, and fewer employment opportunities.

The Great depression, the popularity of the radio, and the increased mobility of the public finished the job. It is, by the way, ironical but not surprising, how the routines once showcased on the wooden street platforms were often literally repeated on the radio and television. Buster Keaton, who grew up in a vaudeville environment, and whose father owned the Mohawk Indian Medicine Company, is but one example of an actor who found inspiration in the Medicine Show routines. Anyhow, by the 1940’s the Medicine Show was a total victim of progress and it was no more than a fading shadow of its past glory. Senator Dudley J. LeBlanc’s Company, promoting his famous Hadacol vitamin supplement (containing a “preservative” 12 % alcohol), is considered as the last big-time Medicine Show. His casting of celebrities as Lucille Ball, Bob Hope, Judy Garland, Hank Williams and Roy Acuff, to name only a few, reflected his high ambitions ensuing in an office box of several million dollars in only 15 months. Jerry Lee Lewis recorded a promotion jingle, the “Hadacol Boogie.” To attract black customers, LeBlanc sponsored a separate touring show featuring notable Jazz and Blues musicians to attract black customers. In 1950 his road show Caravan consisted of 130 vehicles to play one-night stands throughout the South. Next to Coca-Cola, it was then the second biggest advertiser in the USA.

However, the show was over. Therefore, let us reach back in time now to the folk days of the Medicine Show, and look at its role in the American show business and its impact on the dissemination of folk music.

AN OCEAN OF FUN, WITH A LAUGH ON EVERY WAVE

In the nineteenth century, traveling shows and groups were the heart of American entertainment, and the Medicine Shows were no exception next to other road shows as minstrel groups, vaudeville, circuses, Wild West Shows and carnival groups. Yet, I believe that the Medicine Shows were truly unique for several reasons. Without ranking one feature as more important than the other, let me elaborate on some of these reasons.

Though in its first days in the 1880’s, when the Medicine Show had become the act of a group rather than the promotion performance by a lone ‘doc’, the exotic flavor dominated, it has always mixed the different forms of contemporaneous popular entertainment, finding inspiration in minstrelsy, circus acts, Wild West Shows and later vaudeville. The Medicine Show presented a perfect mirror of what the “working class” preferred as stage entertainment, including dancing, singing, comedy and circus acts. For the folk community the show was, as the former pitch man Fred Foster Bloodgood recalled, “a veritable ocean of fun, with a laugh on every wave” (1983).

Furthermore, from all the organized and institutionalized forms of entertainment, the Medicine Show was doubtlessly the one which was most ‘intimate’ with its audience, and had by its physical characteristics the possibility to penetrate the most remote corners of farming communities, flatland or mountain, too small or isolated to attract larger scale entertainment. Although the traveling material of some Medicine Shows could be substantial, they sometimes were no more than a doctor, with a “tripe and keister”, accompanied with another multi talented performer who could sing, dance, and play the kazoo, guitar or banjo. Their proximity to the public, all over the nation, from the East to the West, from the South to the North, made them a most effective channel for communication and the spreading of information in the days when there was no radio, or when the journals were concentrated in or limited to towns or cities.

The closeness went further than the mere relation between an active show and a passive public. The public’s involvement in the act often simply consisted of the pitch man inviting some spectators to engage in some kind of ludic competition as part of the sales strategy, but could be materialized too in the local musicians entering in a one-night contest with the road show’s entertainers. If there was a vaudeville theater in town, the arrival of the Medicine Show group was the occasion for musical interaction. Not exceptionally, the ‘docs’ group resorted to the recruitment of local artists on a seasonal basis, or for a more extended time period. For many African-Americans, for whom the other doors of professional show business remained closed, the Medicine Show was the only opportunity to earn money with their music if they wanted more than just playing in streets or local juke houses. The Medicine Show offered employment and paid better than the street performance.

In these circumstances, it is not surprising that the Medicine Show was a fertile soil for experimentation and dissemination of music. Some songsters alternating moreover employment on the Medicine Show with periods of itinerant street performances, we can understand Jacqui Malone when he states that the Medicine Shows were, next to other traveling shows, “extraordinarily conducive to creative freedom and experimentation. Emerging and established performers could try out new ideas and advance the evolution of their particular art forms” (1998: 58). For black performance styles, they provided a wide cross-section and an arena “in which dancers, comedians, blues singers, acrobats, instrumentalists, and many others could rub elbows.” Paul Oliver contends that “medicine shows may have been the most specific vehicles for the distribution of songs throughout various parts of the country. They were the most institutionalized means by which songsters from different regions could meet, work together and exchange items from their repertoires” (1984: 109). He adds that the exchange was evident: when a traveling show would come to a small town or settlement, it would seek the best musicians in the locality, and they would compete and exchange tunes and songs. The professionals on the Medicine Show had all interest in learning new stuff that was popular. Given the African-American tradition, evidently there would be improvising leading to endless variations and sometimes new songs.

It was imperative that the repertoire was an eclectic mix of popular ditties, novelty tunes, folk songs, dance tunes, parodies, all geared to the tastes of the working class. Though probably not always labeled as such, the blues was part of this repertoire. As Paul Oliver theorizes: “In the early days of the century, when medicine shows and minstrel shows were a commonplace and provided means of regular employment and travel to innumerable musicians, the blues in one form or another would have been readily assimilated by the songsters. The appeal of a new musical form would have been considerable to “professional” folk singers; the technical challenge would have been no problem to them” (1984: 263).

The singularity of the Medicine Show, and its unique American character, were moreover reflected in its multi-ethnic dimension. Especially in its earlier days, and in the most popular Medicine Shows, the white ‘doc’ and other white performers shared the stage with the Indian, fake or real, and African-Americans. Other shows relied on the exotic flavor of the Chinese immigrant to propagate the nostrums and elixirs. The ethnical mix was extraordinary, even if the personae were predominantly stereotype characters.

Though the Minstrel Show had European roots, and its American transformation ensued from white entrepreneurial minds, blacks have played a most important role in it throughout its history after the Civil War. It may very well have been the first place where whites and blacks shared the stage. The medical entrepreneurs quickly understood the fascination of whites with the African-American culture, and they adapted the repertoire to African-American audiences to include tap dancing, ragtime guitarists and classic blues shouters, next to the classic white folk and the Tin Pan Alley tunes.

The racial segregation on the Medicine Show wooden stage platform was much less pronounced compared to the later show business, or even to the contemporaneous traveling shows, and especially to the vaudeville sector where the segregation was built in the concrete of separate black and white vaudeville houses. The major role assigned to the black band in the circus side show came probably closest to the degree of racial integration present on the Medicine Show stage (E. Bosman, 2012).

THE KEROSENE CIRCUIT

In their book “Jazz Dance: the story of American Vernacular Dance” (1994), Marshall and Jean Stearns identify the Medicine Show as one of three types of traveling shows, next to the bigger carnivals and circuses, and the road shows and the T.O.B.A.. The latter, the Theater Owners Booking Association, organized since 1909 the parallel circuit of the black vaudeville theaters, booking jazz and blues artists, comedians, and other performers. By the artists commonly called “Toby time”, or “Tough on Black Artists (Asses)”, the T.O.B.A. set up the performances of the African-American artists in the black vaudeville houses, which flourished beside the white, mainstream vaudeville theater.

The Medicine Shows operated according to a totally different strategy, without having to rely on the mediation of booking agents to connect the audience and the artists. Wherever the pitch man and his group could light the gasoline torches to shine on his mobile wooden platform, in the street or on a vacant lot at the border of the community, the show could draw the crowds. Hence, the “kerosene circuit” of the Medicine Show entailed a much wider flexibility and independence than the more formal touring in the vaudeville theaters. Thanks to its light traveling volume, it too presented a significant higher degree of adaptability to different locations compared to the often big circuses and carnivals.

These aspects are important in evaluating the influence of the “kerosene circuit” in the development and spread of folk and early blues. Too little attention has yet been paid to this circuit. As Bruce Bastin (1984) observed: “the place of these small shows both in helping to spread aspects of the blues and in providing work for traveling bluesmen has never been properly appreciated.” Yet, it is safe to say that the pitch man’s platform was a fertile hub for the “permanent cross-fertilization of ideas and musical styles made available by these itinerant shows, by no means insignificant as influences upon the newly emerged blues tradition ()” (1984: 29).

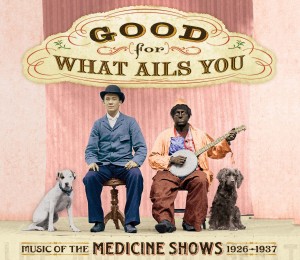

Recently, there has been some accrued attention to the music performed at the light of the gasoline torches. The magnificent album “Good for what ails you”, issued in 2005 by “Hold Hat Enterprises” – an independent North Carolina label dedicated to the preservation of American vernacular and regional music – has collected 48 songs recorded between 1926 and 1937 by Medicine Show “musicianers” and songsters, black and white. It is albeit a small excerpt, but it lets us taste of their immense and delightful repertoire. The liner notes to the CD, written by Bengt Olsson and Marshall Wyatt, provide a lively, very well researched insight in this fascinating world.

Many familiar and less familiar names, associated after 1920 with recorded blues, reported to have started their career on the ‘kerosene circuit’, or to have worked during shorter or longer periods for one or more pitch men. Because versatility was a prime condition for employment, their repertoire was geared at the broad popular taste. It is unlikely that their songs, some of which we would now tend to recognize as blues, were then generally called as such, either by them, or by their public. We can not even state that the blues were for most of them a major part of their stock.

One of the songs (“Atlanta Strut”) collected on the above mentioned album “Good for what ails you” is performed by a songster by the name of “Blind Sammie”, the alias of Blind Willie McTell. As he told John Lomax in a 1940 interview, McTell followed different shows around, Medicine Shows, carnivals, and “all different types of funny little shows.” (liner notes: 57). Gus Cannon called the time he performed at the Medicine Shows the best years he ever had; they were “like one big happy family”. Though he conceded that he “had a shot of liquor before the show” in order to be “funny in front of all them people”, he admitted at the same time that “if there was a doctor show today, I’d be on it” (id.: 71). He joined Doc Stokey’s Medicine Show in 1914, and later happily reminisced that the pitch doctor sold “one bottle for a quarter, or three for a dollar.”

Frank Stokes, who already played the guitar at the turn of the century, and is one of the founding artists of the Memphis Blues, traveled during World War I with Doc Watt’s Medicine Show. Sharing the stage with Mississippi songster Garfield Akers, Frank Stokes performed as musician, blackface comedian, and buck dancer. Big Joe Williams, famous for his mastery of the nine-string guitar, joined a minstrel-medicine show when he was only 9 years old, and stayed with it for 6 or 7 years (Paul Oliver, 1984). He recalls that “they had dancing, cracking jokes, blackface comedians”, and that they “took flour and soot to make you dark”. Sometimes he had to wear a wig.

Sleepy John Estes, as street musician and hobo, worked with Dr. Grimm’s Traveling Menagerie, selling swamp root and other potions and remedies (Ray Harmon). He teamed with Hammie Nixon, who features also in the 1983 documentary “Free Show Tonight”. Furry Lewis joined Jim Jackson on a Medicine Show already in 1906, and would, during the next 15 years, regularly work on such shows. It was not uncommon, he said, to wear “funny things” to make him look like a clown (Paul Oliver, 1984: 99). Jim Jackson, whose later recordings give us a splendid insight in the rich pre blues music, traveled with a number of Medicine Shows, alternating his career with occasional street performances.

Earning his nickname to his stovepipe hat, Johnny Watson, aka Daddy Stovepipe, as a young man traveled with several minstrel and Medicine Shows. Born only two years after the end of the Civil War, he was a veteran of the turn of the century Medicine Shows, when he was, in 1924, one of the first whose blues harp playing was waxed on record.

Born in 1879, Chris Smith was one of the successful black songwriters of the ragtime era, and stepped into show business playing the guitar in a Medicine Show under the direction of an “old actor that had turned to do doctoring”, and who “used to take axle grease and sell it for a nickel a box to colored people for a rheumatism cure” (Dave Bradford)

Pink Anderson, born in 1900, whose musical career took a start by entertaining on the streets of Spartanburg, South Carolina, began at the age of fifteen to tour throughout the Southeast with Medicine Shows. In 1917 he joined Dr. Frank ‘‘Smiley’’ Kerr’s Medicine Show which sold ‘‘snake oil’’ marketed by the Indian Remedy Company. He alternated his work at the Medicine Show with performances on the streets and picnics with other songsters, combining his singing with dancing and comedy. As long as Dr Kerr stayed in the medicine business, Pink Anderson stayed with him, even during the difficult period following the Great Depression, when Dr Kerr had to scale down his big show to a low pitch street level, just like he started twenty years before. A son of Dr Kerr remembers how old Pink “would be in blackface, playing the guitar and singing” (liner notes, Hold Hat Album: 24). Kerr quit the Medicine Show in 1945, and Pink Anderson turned to street playing, occasionally joining, when he could, one or another rare Medicine Show.

In the 1930’s, Pink Anderson had partnered with Arthur “Peg Leg Sam” Jackson, by more than 10 years Pink’s junior. Arthur Jackson had seen Pink Anderson for the first time already in 1922, and they became lifelong friends. Also known as “Peg Pete”, Arthur Jackson was a brilliant example of an extremely versatile artist who combined many talents as harmonica player, dancer, comedian and story teller. He had learned to play two harmonicas at the same time, and in the 1976 biographic documentary, signed Tom Davenport, we see him switching the harmonica almost unnoticed between his mouth and nose. Peg Leg Sam was one of the last original Medicine Show performers, who during his travels had many contacts with other black musicians such as Blind Boy Fuller, Brownie McGhee and Deford Bailey, to name only a few. The 1976 biographic film contains therefore a truly unique piece of footage presenting Arthur Jackson at a county fair in 1972 in the Medicine Show of Chief Thundercloud, vending his “Prairie King Liniment” from the back of his station wagon. As a side note: the 2001 French movie, “Le Fabuleux Destin d’Amélie Poulain”, winner of several awards, contains an excerpt from the documentary.

Peg Leg Sam died in 1977.

THE MEDICINE SHOW WAS MUCH MORE THAN A KINDERGARTEN

Looking at the career of most of the aforementioned and many other artists, it is tempting to consider the Medicine Show as a kind of launch pad for their further career. From this point of view, it provided a perfect environment for learning the ins and outs of the “show business”; it was an ideal stage for acquiring tunes, lyrics and skills from other performers. Indeed, the Medicine Show is often depicted in terms of a training ground, a kindergarten, a transitional phase in the career of an artist whose ultimate goal was mounting the stage, first of the sideshow of a big circus, and later of a vaudeville house. Especially for black artists, who hit the wall of segregation preventing the greater part of them to enter the more organized sector of entertainment, Medicine Shows gave the opportunity for employment, making a living out of music, even if it was only on a seasonal basis.

Yet, I believe that the equation of the Medicine Show to a mere transitional chapter – an introduction – in the career of these artists ignores their talent and obscures the unique place of the Medicine Show performances. True, at a given moment the pitch doctor and his act became outdated, and other forms of entertainment gained momentum, but this does not reduce the Medicine Show and the career of its artists to some developmental stage in a longer perspective. The requirements for successful hawking the medicinal products were tough and very specific. As mentioned above, astonishing versatility and resourcefulness were key requirements and features of the performers. Therefore, there is every reason to depict the Medicine Show as a variety act within its proper terms and characteristics. It was no waiting room or ‘antichambre’ for the bigger stage. Its pure professionalism had to delight the crowds. For each member of the group, its success determined, to use the words of Fred Foster “Doc” Bloodgood, whether it was “feast or famine”.

————————————————–

Glossary

Bally or Ballyhoo: flamboyant pre-show activity, designed to draw a crowd

Grease: any salve

High Pitch: sales pitch delivered from a raised platform

Jake: comic, black face character

Keister (Kiester): portable display case for the pitchman’s wares

Lecture: the doctor’s medicine pitch

Lot: show grounds

Low Pitch: sales pitch delivered from ground level (for instance, soap box)

Mountebank: a hawker of quack medicines who attracts customers with stories, jokes, or tricks.

Pitch: persuasive sales talk

Sambo: comic, black face character

Tripe: tripod used to mount the Keister

Reading

– http://www.memoryelixir.com/lenapeliquid/history3.html

– http://www.artistsandalchemists.com/film/artists/profile/mark_osterman

– http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hadacol

– http://www.mentalfloss.com/blogs/archives/47005

– http://delmark.com/rhythm.estes.htm (Ray Harmon)

– http://www.19thcenturyguitar.com/ (Dave Bradford)

– http://www.io.com/~tbone1/blues/ECblz/pinkan.html (on Pink Anderson)

– http://www.docgrayson.com/history.php

– http://www.heyrubecircus.com/history/the-medicine-show-part-1/

– http://cultureandcommunication.org/deadmedia/index.php/Traveling_Medicine_Show

– http://www.countryworldnews.com/news/texas-trails/523-texas-trails-legend-of-the-snake-oil-salesmen.html

– http://www.bottlebooks.com/kickapoo.htm

– http://www.folkstreams.net

– http://folkstreams.net/context,4 (on Peg Leg Sam Jackson)

– http://harrysmusic.wordpress.com/2008/10/22/week-6-music-notes/

– http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2006/jul/16/23

– http://sundayblues.org/archives/3680

– http://www.fretboardjournal.com/features/online/gastonia-gallop-trunk-full-blues-and-other-tales-obsessive-record-collector-intervie

– http://weburbanist.com/2010/11/30/old-medicine-shows-outrageous-cure-alls-that-will-give-you-chills/

– http://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/ephemera/medshow.html

– http://theoldentimes.com/patentmeds.html

– www.scribd.com/…/Indian-John-Johnson-and-the-Kickapoo-India: Indian John Johnson and the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Show

– McNamara, Brooks, Step Right Up, 1995

– Paul Oliver, Songsters and Saints, 1984

– Bruce Bastin, From the Medicine Show to the Stage: Some influences upon the development of a Blues Tradition in the Southeastern United States, 1984

– Paul Oliver, Barrelhouse Blues, 2009

– Paul A. Prater, The magic of the Medicine Show, 2010

– Jacqui Malone, Steppin’ on the Blues: The Visible Rhythms of African American Dance, 1996

– Album: “Good for what ails you”, OLD HAT CD 1005, 2005 (and liner notes)