[To read the article in magazine-format, click here]

Speaking of his grandfather Omar, who died a slave as a young man, the Jazz player and composer Sidney Bechet once mused: “Inside him he’d got the memory of all the wrong that’s been done to my people. That’s what the memory is….When a blues is good, that kind of memory just grows up inside it.” In all its tenderness, this touching phrase gives us also a glimpse of what is behind the blues as one of the ways in which the black collective memory has expressed itself. But what is a collective memory, and how can it help to understand black culture and consciousness?

No matter how abstract the notion of a collective or cultural memory at first may seem, it is very real in its consequences. Besides the memory of our personal lives, we all have in ourselves, consciously or unconsciously, a collective memory of the past of the group we are part of. Inevitably, through all types of socialization processes, we absorb, mostly without realizing it, values and behavioural codes that are the translation of basic concepts in our culture. By those concepts, we learn for instance to define what is good and bad, what is ugly and beautiful. Furthermore, they settle a hierarchy in our priorities such as the value of individuality relative to the needs of the group. Animals assure their survival from one generation to another by a genetic program; human beings assure the maintenance of their nature by an intergenerational transfer of practices and customs. The ‘past’ of our previous generations shapes our present cultural identity. A collective memory is distinctive from the notion of history, in the sense that the latter is ‘over and gone‘, while the former is still very much alive in what we do in our everyday lives. The collective memory contains the elements of the past that are still relevant today, and steer our actual thinking and actions.

A collective memory is not static. It evolves dynamically relative to the social context, the economic environment and its interaction with other groups in society. A change in the context will over time change the functionality of the components of a collective memory reducing them to ‘dead’ history.

So far for the theoretical talk. I do not want to bore you any longer with it; my point is that when the ancestors of Sidney Bechet’s grandfather set foot on the American soil, they brought along a very vivid memory of their culture. Call it a comprehensive world view, a “Weltanschauung”, a collective philosophy of life: a framework in which to interpret the world. As Africans they shared basic beliefs, interpretations of good and evil, a view on their place in nature and the cosmos, a definition of past, present and future and what role their ancestors played in this, …. The hardships of the Middle Passage did not erase their collective memory.

When the Africans arrived in America, nothing of their cultural memory was materialized. While Western dead and living past is translated in writing and other media, and in the concrete of monuments, all the slaves carried with them were their rags and their spirits. Those were, however, enough to ignite the black consciousness that has been, and still is an integral part of American history and that has left, moreover, an ineradicable print on our Western culture. Obviously, the slaves’ cultural memory would undergo changes: not everything that was functional in their homeland would remain so in the New World. How could it? Their very existential status had changed from human to chattel property. But, most importantly, though this premise was far from accepted until a few decades ago, the New World did not choke the African memory. On the contrary: it provided the bondsmen with the spiritual tools that allowed them to survive in their new environment, dynamically and creatively selecting from this New World the elements that enhanced the efficiency of those tools. As the New World evolved, and as the status of the African(-American) changed, so did their cultural memory.

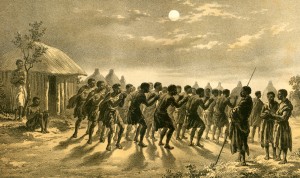

For more than two and a half centuries, the black cultural memory would be kept alive only in an oral tradition, through storytelling, and especially through music and dance. For the slaves, reading and writing were forbidden areas. So, the African lore found its natural expression in the tales of all kind handed over by one generation to another, complemented by their music and dance giving voice to their world view and spiritual beliefs. There is a vast documentation on the importance of sound in African culture and how music and speech were part of the same equation, at the same level as dance. Dance was music, as music was dance and both acted as a communication medium not only with the living, but also with the dead, the ancestors. It was a form of intergenerational transfer of information.

The interpretation of black music, in whatever form – from spiritual to blues and jazz – can only gain from placing it in the larger realm of the black cultural memory as it developed over the past centuries. Since a few decades, the essential place of the ring shout in this black universe, and thus in the unfolding of black music, has been explored and recognized. If you can spare me a few minutes of your time, I will now try to elucidate how this activity was the fertile soil on which would blossom such music as the blues.(1)

THE CIRCLE and THE CIRCLE DANCE

First, let us go to Africa.

Westerners think in a linear way. By a step-by-step reasoning, they progressively build up arguments based on previously gained insights to unravel whatever problem presents itself. In Africa, on the contrary, the circle bears a high value. It is the symbol of balance and the sign of unity between philosophical principles that at first sight look unreconcilable. The circle, inspired by the movement of the sun, the turn of the seasons, and by the life cycle also stands for continuity. Furthermore, it was intimately linked with ritual practices, even to such an extent that for missionaries the circle became the chief symbol of heathenism.

Though in different African cultures the circle ritual had different meanings (embedded in such various events as “rites de passage”, funerals, marriages, births) , the counter-clockwise direction of the movements, reflecting the sun movement, was a common characteristic.

By the vigor of the movements and the music performed in the circle dance, contact was established with the deities, the supernatural, the “orisha” who rule over the forces of nature. One of the chief “orisha” is Eshu (also Elegbara), worshipped in many, related forms across Africa (and in the African Diaspora in the New World). He is the God of communication and spiritual language, the gatekeeper between man and the higher spirits, and as such he is the interface with the whole cosmos, the doorway to the larger universe, the medium between this world and the other. Like the other divinities, he is a God who is very much alive and who connects the larger universe with the everyday life. He embodies all the forces, whether they are positive or negative. He is thus neither bad, nor good; he controls fortune and misfortune and is the guardian of secrets. He represents the balance of nature, day and night, construction and destruction. Eshu, as a mediator or delegate of God, will ensure that rewards and punishments will be given, but in this capacity he can be courted and bribed. There is, in this view, no absolute polarity between good and evil. Unlike the Christian belief, the Eshu belief system does not assign an ultimate cause to evil since evil is an imperfection, a not-entity, the absence of good. Because evil does not require the presence of a cause, there is no room for a Christian concept as the Satan-devil who does nothing but evil, in contrast to a God who is the source of all what is good.

Most importantly perhaps, Eshu-Elegbara is an ultimate trickster who incorporates all the basic characteristics of such a persona: deceit, humour, lawlessness, and sexuality. He is the mischievous creative spirit who frequently leads man to temptation and possible tribulation in the hope that the experience will lead, at the end of the day, to maturation. Like other trickster figures in mythology, Eshu-Elegbara breaches the law, the moral codes, he is inventive, a master of “bricolage”, who, by wit can invert situations and transform the environment, creating chaos out of harmony, and order out of dissonance. The transgression of the sexual boundaries is one of his most visible characteristics, which probably contributed largely to his definition as the devil by white missionaries, who completely misunderstood the role of Eshu. We note in this context that Eshu has also been depicted as a shape-shifter, who can transcend the gender boundaries. Sculptural representations show “him” often as a conjoined phallic male and female figure, or as a hermaphrodite who holds her breasts in her hands.

Eshu-Elegbra’s main sign is the crossroad of which he is the embodiment, the owner. He offers choices and possibilities. At a crossroad, a man has to recognize truths, make decisions that can be life changing. Crossroads are a place of ambiguity, like the very nature of Eshu-Elegbra who can be both young and old, violent and yet be at the origin of harmony and balance. He is profoundly a paradoxical figure too wicked to have a wife and children, with no other home than the crossroad, or sometimes the marketplace.

The circle served to define the space where Eshu was invited; the music and the movements, the clapping of the hands and the stomping of the feet, accompanied by the strong beat of drums and gourds, the strong rhythmic accelerations eased the possession of the dancers by the higher spirits and by the spirits of their ancestors. The circle dance connected in a direct way the living with the supernatural and the ancestors. It was the ultimate expression of a world view that emphasized the wholeness, the interconnection between the living and the dead in a universal cosmos that, unlike Western culture, made no distinction between the sacred and the secular. This insight, I believe, is crucial to an understanding of the ring shout, a transformation of the circle dance in the New World, and by this also to a richer interpretation of the evolution of black culture and music.

THE RING SHOUT IS NOT A SHOUT

The “Encyclopaedia of African American History” defines the ring shout as “a kind of holy dance in which the participants move counterclockwise in circle, hardly lifting their feet from the floor, knees bent, leaning slightly forward from the hips, and making movements expressive of the lyrics sung by a “leader” and “basers” or chorus in call-and-response fashion, propelled by cross-rhythms produced by foot stomping, hand clapping, and often a “sticker”, a person who beats a broom handle or a stick on the wood floor. The shout usually begins slowly and gradually builds in intensity. Sometimes a shout might last and hour or more and a shout service for hours“.

The phrasing of the definition, using words as “a kind of“, “often“, “usually” and “sometimes” is in the first place indicative of the variants that existed. Secondly, and more importantly, it testifies to the difficulty to catch the African culture in Western concepts. Was it a “holy” dance? The word “holy” presupposes a secular world, and as we described above, this distinction was not relevant in the African cultural memory. Is it a “dance”? The word “dance” has connotations of entertainment, which it clearly had not in the African context. Furthermore, the label “ring shout” is strongly misleading, since a “ring shout” is not a “shout”. The term has been coined for the first time in 1860 by an unidentified Englishman, but is wrongly associated with the English word “shout”. Though some scholars disagree with his theory, Dow Turner suggests that the word’s origin lays in the Arabic word “saut“, a term used to describe the circular ritual movements practiced in parts of Islamic Africa. Note that Muslims walk around the Kaaba in Mecca in a counterclockwise direction. Finally, a “ring shout” should not be equated with spirituals or songs. The vocal component is not essential to the definition of a ring shout. “Shout songs” or “running spirituals” have only been defined by twentieth century observers as a specific category when the the conversion to Christianity had infused the African rite. In the words of James W. Johnson and John R. Johnson: “[There] are the “shout songs”. These songs are not true spirituals nor even truly religious; in fact, they are not actually songs.”

Upon its arrival in America, two essential features of the “ring shout” were, I believe, the “circle” and the “spiritual possession“, that symbolized a reality defined as a continuum unifying the present, deities and ancestors, referring thus to a cosmological wholeness of space and time. The fundamental organizing principle of the “circle” becomes more obvious when we compare it to the “line” formation, dominant in the European dances such as the “contra dance”, a general term for folk dance styles in which couples dance in two facing lines. A “line dance” does not allow the kind of mediation between the individual and the spiritual forces envisaged in the African culture. Unlike a “line” movement, the “circle” movement keeps the participants together in a “gathering” place.

A third feature was the strong emotional commitment, mingled with the ecstatic “spiritual possession”. This dimension still prevails in the African cultural memory: religion is not something that can come from the book. If you haven’t “felt” it, “you ain’t got it”. In the process of the conversion of the slaves, this feature also helps to understand why certain Protestant denominations which emphasized emotionalism found easier access to the spiritual world of the bondsmen than other sects which had a more “instrumental, mechanical” approach to Christianizing.

Doubtless, it is exaggerated to contend that the “circle dance” was the only building block upon which black culture developed in the context of the New World. Nevertheless, it is impossible to ignore its primary importance when it comes to understand African-American black consciousness and its different forms of expression. Because the slaves had different ethnic backgrounds when they arrived on the American continent, they also brought along different cultural backgrounds that echoed variations in customs and practices in their homeland. Though Eshu- Elegbara and other divine entities shared common features, there existed at the same time important ethnic divergences. This is where the “ring shout” comes on stage as a unifying element. Authors as Samuel Floyd have argued that the “ring shout” has taken on an enhanced significance in discussions of African survivals in the New World as an activity that became “central to the cultural convergence of African traditions in Afro-America.” In his discussion of the evolution of African American dance, Finkelman notes that, even if the dance took many different forms, it was an important constituent element for African-American cultural identity. Hazzard-Donald observes that bondsmen clung to this cultural memory as a means of psychological survival. According to Sterling Stuckey, a leading cultural historian and authority on slavery, the circle dance enabled the slaves to recall the traditional African community and,

“to include all Africans in their conception of being African in America. They discovered, despite the presence of different ethnic groups () that they shared an ancestral dance that was common to them in Africa. Just as they crossed actual boundaries in being brought to America, enough were able to make an imaginative retreat to the ancestral home to discover, in the Ring Shout, the ground of cultural oneness.”

The circular dance suggested a wholeness that encouraged the spirit of community among the Africans who were deported to the New World. It helped the slaves to overcome barriers of language and ethnic differences, becoming thus an instrument of “black unity.” It was the main context in which transplanted Africans recognized values common to them.

The “ring shout” was thus a vehicle through which the African slaves brought their ideology in America. The slave-holders had absolutely no idea of the prominence of the circular ritual, and which they looked (down) upon as a savage, primitive, barbarian dance devoid of any spiritual meaning. In the Euro-Christian tradition dancing is usually not associated with religious activities. The irony grows stronger when we recall that the circle dance was the medium by which the Africans allowed their Gods and ancestors to “take” their spirits, to exert extreme power over the dancers, right under the very eyes of the “worldly” slave-owner. The “dance” eschewed the distinction between their everyday life of bondage and their spiritual world. As master, the slave-owner was degraded to an external, powerless observer without even realising it.

TO CROSS or NOT TO CROSS THE LEGS

Obviously, enslavement meant a fundamental rupture with the traditional African context. The structure, meaning and function of the circle dance could not stay the same. It was reconfigured to the new physical and social world where the Africans were forced to live. Some slave-owners tolerated the ring shout in their ignorance of the meaning of the “dance”, others banned it as a barbaric activity. The often sexual connotations the white attached to certain bodily movements was not entirely strange to the prohibition, by some, of the dance as being heathenish and sinful. The ring shout was often relocated to secret places in the forest or the fields, out of the eyes and ears of the whites.

In any case, the ring shout became a main instrument by which Africans showed their imagination in adapting their cultural memory, customs and practices to a changed environment. It is a fine example of the theory, developed by Melville Herskovits – a major American anthropologist – of reinterpretation of African traditions. The new environment was of course in the first place the one created by being forced to work as chattel property on the plantation. The African bodies were enslaved. Secondly, and especially from the end of the eighteenth century on, the process of conversion to Christianity took off, supported by an increasing conviction in the minds of the slave-owners that conveying the Christian concepts to the bondsmen could be beneficial to the docility of their labor force. It was the start of the mingling of the shout dance with Christian themes and motifs.

The encounter of the African and Christian belief system was nothing less than fascinating to observe, and once more showcased the creativity of the Africans to express African meanings and values through Western cultural forms. The ‘merger’ was based on an ingenious eclectic process that at the end of the day led to the creation of a new system which was totally African-American, adapted to the needs of the black populace. The American cultural anthropologist Paul Radin has formulated it in an unmatched way when he wrote that “the ante-bellum Negro was not converted to God. He converted God to himself.” The blacks molded a new cultural memory by importing and interpreting different elements from their new environment in accordance with the perspective of their homeland.

It was only natural that the ‘ring shout’ attached itself to the conversion process and to the blacks’ Christian worship. Bodily movements and chants in the ring shout were intimately linked with contacting the ancestors, the higher spirits, the Gods. Because African dance and spiritual possession were one and the same, obviously, Christian conversion and the ring shout were bound to meet each other. Their relation was however of a complex nature.

To say the least, the missionaries and the converted community marginalized the ring shout. The intolerance took even the form a clear-cut ban by such active missionaries as Bishop Daniel A. Payne, president of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) who spoke of the ring shout in terms of an “incurable religious disease“. The pelvic movements exhibited during the dance suggested in the Christian eyes sexual activity, and were unambiguously labeled as “dirty”. In the African perspective, sex has a totally different meaning: sexual intercourse is creative and holy, and the allusions in the songs and movements are respectful and far from obscene. Anyway, for the white the ring shout was reminiscent of the African religion and thus considered as a sign of superstition, a worship to African Gods such as Eshu who were, as we have mentioned above, equated by the white missionaries, with the devil.

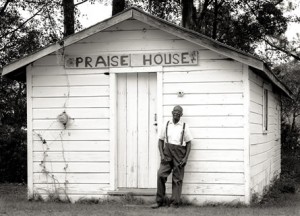

All contemporary eyewitnesses confirm that the ring shout was an activity that was distinctly kept apart, in time and place, from the regular Christian worship. On Sunday, the slaves accompanied their “Master” and “Mistress” to the formal prayer meeting and preaching service in the church, during which the word was spread among the black that a ring shout was to be held after completion of the white ceremony, on “hush harbors” or in “praise-houses”, removed from white control. W.F. Allen, one of the authors of “Slaves Songs of the United States”, has left us a vivid account of a shout on the Sea Islands:

“…the true “shout” takes place on Sundays or on “praise”-nights through the week, and either in the praise-house or in some cabin in which a regular religious meeting has been held. Very likely more than half the population of the plantation is gathered together… But the benches are pushed back to the wall when the formal meeting is over, and old and young men and women…boys…young girls barefooted, all stand up in the middle of the floor, and when the ‘sperichil’ is struck, begin first walking and by-and-shuffling round, one after the other, in a ring. The foot is hardly taken from the floor, and the progression is mainly due to a jerking, hitching motion, which agitates the entire shouter, and soon brings out streams of perspiration. Sometimes they dance silently, sometimes as they shuffle they sing the chorus of the spiritual, and sometimes the song itself is also sung by the dancers. But most frequently a band, composed of some of the best singers and of tired shouters, stand at the side of the room to “base” the others, singing the body of the song and clapping their hands together or on the knees. Song and dance alike are very energetic, and often, when the shout lasts into the middle of the night, the monotonous thud, thud, thud of the feet prevents sleep within half a mile of the praise-house…”

The architectural design of the white church, with benches lined up and facing a pulpit, was in any case not adequate for the ring shout. As simple wooden constructions, on the contrary, praise-houses were physically perfect for the practice of the ring shout. Former slaves’ narratives tell us also how, in a praise-house, often a large tin basin was overturned and raised to the rafters to “catch the sound” in order to lessen the likelihood that the gathering would be discovered. Often, the basin or barrel was filled with water and set in the middle of the room or by the door, believing that it could serve the similar purpose of dampening down the sound. Praise-houses became the centres of the African-American religious life, the locus of ritual practice and ecstasy. They were the basis where the ring shout began to give expression to a gradual merger of African and Christian beliefs.

The irony is that for many African-Americans the ring shout was experienced as a necessary path to conversion. The emotion involved in the “dance” was, after all, a basic feature: religion is a feeling that “comes” to you, it is not conveyed by an unemotional reading from a book by a minister in the pulpit. That is why the enthusiastic and ecstatic environment of the camp-meeting revivals – even if blacks and whites were physically separated – were seen as the ideal place where African response patterns could be merged with Christian interpretations of the experience of spirit possession. As a contemporary expressed it: “Sinners won’t get converted unless there is a ring“.

In line with the African conflation of what Western culture tags as “secular” and “sacred”, the ring shout was not limited to spiritual events, but was also performed at secular occasions such as the corn-shucking and other post harvest celebrations. The lyrics were not always of a spiritual nature, but had quite often a secular reference. It has been observed moreover that shout rhythms were sometimes made to simulate a rail-road train. Even in the face of the conversion process, the ring shout stayed in the first place a symbol of community and of respect for the ancestors, reflecting both sacred and secular aspects of life.

It is in the context of the conversion efforts and the relation between the secular and sacred realm that, I believe, the discussion on the importance of cross legging during the ring shout needs to be evaluated. Many descriptions highlight that converted slaves (and freedmen) shuffled around the circle without crossing their feet. The feet-crossing was considered as the barrier between proscribed dancing on the one hand, and perfectly acceptable forms of religious expression, on the other hand. In the Christian perspective, dancing during the religious service was not allowed, and Baptists defined dancing as crossing the legs. Because dancing was essential to the spirit possession, in an African framework, it is frequently stated in documents that avoiding to cross the legs during the ring shout was a way to make the dancing acceptable in the black Christian worship. As long as the legs were not crossed, as they were in European-style dancing with a partner, the dance could be seen as a valid way to express religious fervour in the black churches, even if the dance was often lascivious. To cross the legs was to worship Satan. Not to cross the legs was to worship God.

Curiously, there is no certainty whether the crossing of the legs has ever been a feature of the shout when it was initially performed, nor do we have an idea when the slaves would have ceased to cross their legs during the shout (Stuckey). I believe, however, that the very existence of this discussion is more relevant than the importance of ever finding an answer to the questions at stake. In the light of the later cultural evolution, the introduction by the Christian belief of a distinction between the sacred and secular is in my opinion much more significant, since this distinction was foreign to black cultural conscience. The activity of the ‘ring shout’ acted thus as a kind of forum where Christianizing phased in concepts extrinsic to the African traditional culture. In the latter, dancing was not an act of entertainment, but a medium of spiritual experience. In the Western concept, dancing was a profane, secular activity. The discussion on the leg crossing materialized a debate on the reconciliation between two different world views.

If, as we described above, the circle dance was a way in the African homeland to invite Eshu, the ultimate trickster, the medium between the everyday life and the spiritual world, where did this God find his place in the black consciousness in the New World? Eshu as such did not survive the Middle Passage, but was still present in the cultural memory of the bondsmen, though in other shapes. In the first place, the devil in the spirituals was originally more a trickster figure than the Western concept of the devil, as external and exclusive source of evil. Paul Harvey said it as follows: “slaves also brought their own images and literary devices into the spirituals, which spoke as much of their African heritage as of their White Christian training. () The devil portrayed in the spirituals bears a more striking resemblance to the conjuring trickster of West African folklore than to the unambiguously evil Satan of Christian tradition.” (p. 141). I will come back on this in a few minutes.

Secondly, the trickster figure staid very much alive in the many folk tales that continued to feed the cultural memory, generation over generation, and which staged human and, mainly, animal trickster figures. L.W. Levine, among others, has shown the importance of the slave folk tales as expression of the black consciousness. Next to their didactic function demonstrating ways of surviving, the trickster tales presented scenes where the weak controlled the arbitrary power of the strong. They acted as question marks to the existing relations of authority between the master and the slave, without the former being aware of it. It gave the slaves a sense of psychic relief and a sense of authority in an environment characterised by the meaninglessness of the white’s rules. Doubtless, the cycle of the Brother Rabbit and the Wolf tales, popularized for the mainstream audience in the late 19th century by Joel Chandler Harris (1845-1908), who wrote up and published many of them, was the among the most spread ones. There existed a wide variety of stories.

In one of them, the wolf leads the rabbit into a hollow tree which is set afire. But the rabbit outsmarts the wolf: it escapes through a hole in the rear of the tree and convinces the wolf that there is food in this tree, and in all the other trees in the area. The Rabbit tricks the wolf into entering one of those trees in search of food. Needless to say that the tree does not contain food; on top: it lacks an escape hole. The weak rabbit has now total control over the situation and dominates the stronger wolf: he sets the tree afire, and the wolf burns to death. By its wit and cunningness the rabbit has succeeded in reversing the authority and power relations to its own profit. Was the rabbit one of the presentations of the shape-shifting God Eshu?

The same question is valid for another folk trickster figure, the “signifying Monkey”, that is said to have originated during slavery. As in the Brother Rabbit tales, the Monkey manages to dupe a stronger animal, in this case, the powerful Lion. He does so by “signifying”, this is: using figurative ways of speech, or a code language understandable only to those who share his way of thinking. Brother Rabbit and the signifying Monkey became the heroes of Black culture and consciousness. The trickster tales can interpreted as the transformation of African symbols in the New World. The literary critic Henry Gates has convincingly argued that the Eshu-Elegbara God became the “signifying Monkey” when he came to America. In fact, both the Rabbit and the Monkey engaged in “signifying”, using verbal strategies of deceit, upon their stronger opponents. Didn’t the black storytellers signify in the same way upon their masters? Their stories were understandable only for the other slaves; the whites only heard the factual story: amusing tales about animals, stories which they even stimulated as they were entertaining for their children. Was this “trickery” also not present when the slaves performed the ring shout, letting their supernatural forces control them, before the very eyes of their worldly masters?

THE LEGACY OF THE RING SHOUT

Cultural memories evolve slowly, but can alter more quickly as a result of abrupt social changes. The Emancipation in 1865 was such an historical watershed. Nevertheless, a time-line is seldom straightforward and one dimensional: some relics continue to function for a while, simultaneously with new activities. Such was the case for the ring shout, which did not disappear from the scene, even if the Emancipation created a radically new context where the ring shout would loose much of its initial meaning and objectives. In fact, most of the extant descriptions of the shouts are post-bellum, and some date back to as recently as the years preceding World War II.

After the Civil War and the Emancipation, when the fences of the plantation were torn down, and the geographical and social horizon of the African-American widened, the cultural memory drifted further away from the African homeland. The migration flows to towns and cities gradually transformed the black cultural traditions. Simultaneously, the conversion process that had started before the Civil War intensified, largely accounted for by the increased efforts by black churches. The fight against illiteracy was an essential component of the Christianizing. No matter how humanitarian their objectives were, most of the abolitionists who descended from the North to assist the new freedmen evaluated the African-American culture in a way that was not very different from the Southern perspective. The customs and practices from the black populace were labeled as primitive, barbaric, and the only way to bring them ‘civilization’ was to Christianize them, and to learn them to read, write and think as Western people. The magic circle was more and more broken, and as Katrina Hazzard-Donald has shown, the black urban dances, though keeping formal elements of the ring shout, would incorporate, in parallel with other cultural developments, more and more elements of ‘line-dancing‘.

The slavery during the pre-Civil War period had induced a high degree of homogeneity in the black consciousness. Despite regional variations, the basic conditions had been the same almost everywhere. The ‘institution’ of slavery had defined in an unambiguous way the boundaries within which the slave culture could develop, and, as I have noted above, the ring shout had been a significant unifying activity that had helped to build up the self-identity, and self-respect in the face of a system that denied humanity to its labor force. Through different mechanisms, the Emancipation and the intensified conversion resulted in an increased heterogeneity on different levels. One of the most significant consequences of the Emancipation was without any doubt the newly acquired freedom by African-Americans to move around freely. This was not only psychologically of tremendous importance, it meant also that the freedmen could decide where to look for new work, and a new place to start their lives. The self-containment typical of slavery was replaced by a larger social exposure after the Civil War. For some of the black, the geographical mobility lead to some social mobility. The African-Americans staid no longer an undifferentiated mass of agricultural workers; even if as a group they staid at the bottom bar of the social ladder, distinctions on the basis of status became more and more noticeable.

The uniform, simple wooden praise-house functioning as central social and religious gathering places, and as one of the symbols of the self-contained homogeneity of slavery, was replaced by the black churches. Their proliferation was impressive: black churches experienced a very rapid growth after the Civil War, with black missionaries spreading all over the country. The religious institutions, established separately and independently from the white churches, started to claim their prominent role in African-American live, and laid the foundations from which they would be the inspirational source for later political action. A striking feature of the black religious institutions was their divergence about their doctrines and styles of religious performance. Though Baptists and Methodists were dominant, a whole range of other denominations or congregations blossomed. Their diversity was often measurable by the ideological distance to their white counterparts, a distance which greatly overlapped with the social status of their members. Many African-Americans held their worships in store-front churches, former stores that had went out of business, and that were cheaply rented to financially weak Congregations. It is no coincidence that the religious services in the latter were much more reminiscent of the enthusiastic Congregational participation in the former praise-houses, than the gatherings in the bigger black churches where the service was more inspired by the white, placid and still evangelical approach, and where the singing was often confined to standard hymns and selected spirituals. The religious affiliation of the African-American had become the most significant factor that determined the style of the religious gathering and the music performed.

As said, the ring shout did not disappear from the scene in this existentially different social context where black churches replaced the former praise-house, and where jook-houses became the place where the African-American could give expression to his more worldly concerns and thoughts. Though not in its original form, the ring shout continued to influence black consciousness and African music.

Elements of the ring shout survived in some of the (smaller) black churches sacred dances, especially in the holiness churches. “Drums, percussion and hand clapping, and vocal improvisations provided the musical background for religious dances” (E.G. Price). The ring shout was inspirational also for the dances on the minstrelsy stage and other secular dances. The “walk-around”, a featured dance of the Minstrelsy, resembled the activity of the ring shout, as did the “essence dance”, which consisted of slow movements and sophisticated manipulations of the heels and toes. The tap dance variant, ‘soft shoe’ developed through black minstrel reinterpretations of the “essence dance”. Elements of the ring shout would later be integrated in dances as the Big Apple circle-dance, the Charleston and the Black Bottom. The latter would become a craze in the twenties, not only in America but also in Europe.

Following earlier work by authors such as Sterling Stuckey and Harald Courlander, Samuel Floyd unambiguously labels the ring shout “the foundation of Afro-American music.” There are many arguments for it.

Already above, I quoted Sterling Stuckey who saw in the ring shout the main context in which common African values were recognized. Furthermore, the basic elements that define African music are present in the ring shout. To mention only a few of them: the calls, cries, hollers, call-and-response techniques, the poly-rhythms, the off-beat melodic phrasing and the constant repetition of rhythmic and melodic figures. The ring shout was the cradle where African music in the New World could take shape.

Perhaps less obvious at first sight, the intrinsic relation between dance and music in the ring shout is a defining feature of much of the later black music such as blues and jazz. Already in the African homeland, the circle movements blended in an inseparable way dance and music. So it is for blues and jazz. In the words of Tera W. Hunter: “African-American music has been an engaging social practice where audience and performers are expected to respond to one another with oral and physical gestures. () Like its ancestors, the blues inspired active movement rather than passive reception, and dance provided the mechanism for the audience to engage the performer in a ritual communal ceremony. () The blues served as the “call” and dance as the “response” (…)“. Or, as the essayist Albert Murray stated: as in the ring shout “black music disposes the listeners to bump and bounce, to slow-drag and steady shuffle, to grind, hop, jump, kick, roll, shout, stomp“. Throughout the whole history of black music, black listeners have also been dancers. “Didn’t no dance go on without the blues”, declared Thomas Dorsey.

That music and dance were virtually inseparable, brings me to two other survivals of the ring shout, on a more general level, which I can within the framework of this essay, however, only skim over. Moreover, both are nothing less than controversial, and I’m certain many of you will (strongly) disagree with some of my observations below.

DID ADAM & EVE EXPEL THE RABBIT &THE WOLF?

Because African dance and music in, what Christians label, a secular and sacred context share a common pedigree in a cultural system that makes no distinction between both dimensions, the close link between blues music and dance has given the religious and middle-class African-Americans quite some headaches. The latter, from an Evangelical perspective, insisted strongly upon making a difference between “shouting” for the Lord, and “shouting” for the devil. The biggest (and richest) black churches made therefore a strong case to divorce themselves from traditional styles of worship, preaching and singing which they considered as “heathen”, reminiscent of Africa and of the slavery period (T.W. Hunter). The blues would gain notoriety among blacks (and whites) as the devil’s music, the antithesis of Godly music (S. Calt). The equation between the blues and the devil would become part of the mythology, cleverly capitalized not only by the white owned recording companies, but also by a large part of the religious community. The blues was not only threatening for the latter because it was secular music, but probably also because its performers and “its ritual too frequently provided the expressive communal channels of relief that had been largely the province of religion in the past” (L.W. Levine). The devil was a strong symbol for the religious community to deter their members from entering the sinful places of dance and music. At the same time, I am tempted to say, the devil acted as a promotional strategy in the membership drive of the black churches. The impact was substantial: the secular-sacred dichotomy crossed the view on music by generations living under the same roof (as it was for instance the case for W.C. Handy), and split even the careers of many a bluesman.

Nevertheless, from the point of view of African cultural legacy, blues reunited, I believe, both the secular and the sacred. Many blues performers have stressed this blending in their work. Alberta Hunter declared that her blues were almost religious, almost like spirituals, almost sacred. Sidney Bechet defined spirituals and the blues as prayers, where one was praying to God and the other was praying to what is human. B.B. King felt like being in church and wanting to shout when he performed. Charley Patton was not the only bluesman who had also religious music on his repertory. Also scholars have highlighted that it is often very hard to draw a distinct line between the blues and spiritual songs. John Szwed, Professor of Music and Jazz Studies at Columbia University, argues that the bluesman is like a shaman who “presents difficult experiences for the group, and the effectiveness of his performance depends upon a mutual sharing of experience…Church music is directed collectively to God; blues are directed individually to the collective. Both perform similar cathartic functions but within different frameworks.” James H. Cone believes that the blues and spirituals flow from the same bedrock of experience, and neither is an adequate interpretation of black life without the commentary of the other. Observing that blues shows no attempt to make a distinction between worldly and divine truths, he calls the blues “secular spirituals”: blues and spirituals partaking of the same black “Essence”. J.M. Spencer contends that the “ethos of the blues is thoroughly religious.”

It has, by the way, been repeatedly stressed by many that the techniques of preaching in church were not different from performing the blues, at least if we compare the latter to the ecstatic-enthusiastic religious services in some black Congregations.

Closely related to the Christian induced cleavage between sacred and secular, is the phasing in of the concept of evil emanating from the devil. As I already said above, in the African world view, the God Eshu-Elagbara was neither good nor bad. The traditional African spiritual view had no such notion as Satan. Instead, the trickster played the title role, and his work was sometimes evil, sometimes beneficial. He was part of a cosmos in which opposing supernatural powers were ultimately complementing each other. Along with the conversion, the Christian entity of the devil, as the lord of evil, entered the African-American culture. However, the transformation happened gradually, again incorporating the Western forms into the African framework. This way, Satan initially kept some of the Eshu-Elagbara trickster features. The slaves’ idea of a Satan was different from the evangelical understanding of good and evil held by the masters (W. Poole). Satan could on the one hand be fearful, but could at the same time be a powerful trickster figure instead of an evil force. He had the power of a “conjurer”, a sorcerer. At the same time, he could also be a neutral power who brought laughter and celebration.

The early devil concept held by the African-Americans was thus a complex one, as is testified for instance by documents telling us of slaves who, despite viewing the banjo and the fiddle as tools in the hand of the devil, were not scared by these instruments. Quite on the contrary: the banjo and fiddle acquired a supplementary value as they could connect, in their view, with the supernatural. The early black devil in his disguise of trickster was perfectly complementing the functions of the Rabbit and the Wolf tales.

As the acculturation spread, so did the Biblical concept of good and evil, and the case “God versus the Devil” grew stronger in the African-American culture. Black musicians, very often raised in Christianized families, were naturally familiar with the Evangelical view of the devil as the author of all evil, and with the story of Adam and Eve who had been tempted by the devil, dressed as a snake, to eat the forbidden fruit. In his “Adam and Eve” blues, Tommie Bradley, sang in 1930: “Because Adam said to Eve: “You think you’re so cute, / You wouldn’t give me none of that forbidden fruit.” Sippie Wallace, co-author of the song “Adam and Eve had the blues”, declared to have found her inspiration from a bad marriage due to her husband’s infidelity, a sin which all men supposedly committed because of what Eve did in the Garden of Eden. In an interview in 1985, Sippie Wallace shares her story on the origin of the blues with the interviewer Christopher Brooks: “And so, he [God] drove Adam and Eve out of the garden. And that’s how we come to have the blues. Eve was the cause of it. Now, if that had been a man and did what God told him to do, we wouldn’t have the blues. Since that day, everybody has had the blues.”

The devil figure is a frequent actor in the blues. H.A. Baer and M. Singer argue however that there is no unique presentation of him. They distinguish three types of devils in blues songs. Firstly, the devil is often equated with the “blues”-feeling itself, in the sense that the devil is the embodiment of personal sadness, depression, agony, hard times and harsh lives. In a second form, the church, and more particularly the “hypocritical” ministers who emulate the white congregations, is presented as the devil. In still other songs, thirdly, the devil is the very behaviour of the bluesman when he engages in activities (drunkenness, violence, sexual misconduct,…) which are condemned by the church.

Did Adam and Eve relegate the trickster persona, popularized in such figures as the rabbit or the signifying monkey, from the lore of the African-Americans? They did not. Baer’s and Singer’s classification of devil figures in the blues needs to be completed with a fourth category. There is indeed also the devil who emerged at the crossroads to grant superior creative skills to black songsters (L. W. Levine). Though his attitude towards African-Americans is outdated, the hundreds of stories collected by the sociologist Newbell Niles Puckett in his 1926 publication “Folk belief of the Southern Negro” are still very relevant to understand, what he calls, the “feelings, emotions and the spiritual life of the Negro.” One of those stories, collected directly from old black folk, taking place at a crossroad, goes as follows:

“Sit down there and play your best piece, thinking and wishing for the devil all the while. By and by you will hear music, dim at first but growing louder and louder as the musician approaches nearer. Do not look around; just keep playing your guitar. The unseen musician will finally sit down by you and play in unison with you. After a time you will feel something tugging at your instrument… Let the devil take it and keep thumping along with your fingers as if you still had a guitar in your hands. Then the devil will hand you his instrument to play and will accompany you on yours. After doing this for a time he will seize your fingers and trim the nails until they bleed, finally taking his guitar back and returning your own. Keep on playing; do not look around. His music will become fainter and fainter as he moves away. When all is quiet you may go home. You will be able to play any piece you desire on the guitar and you can do anything you want to do in this world, but you have sold your eternal soul to the devil and are in this world to come.” (p. 554)

Puckett moreover heard that in the African-American culture the devil is a very real individual, capable of taking almost any form at will. His interviewees told him that the fiddle or banjo “is thought to be a special accomplishment of the devil () Some go as far as to say that playing the violin is actually an audacious communication with Satan himself. Take your banjo to the forks of the road at midnight and Satan will teach you how to play it.”

Doesn’t this story sound very similar to the one told by Tommy Johnson:

“If you want to learn how to make songs yourself, you take your guitar and you go to where the road crosses that way, where a crossroads is. Get there, be sure to get there just a little ‘fore 12 that night so you know you’ll be there. You have your guitar and be playing a piece there by yourself…A big black man will walk up there and take your guitar and he’ll tune it. And then he’ll play a piece and hand it back to you. That’s the way I learned to play anything I want.”

The big black man embodies the same devil figure who supposedly met Robert Johnson when he disappeared for a few weeks only to come back as a highly talented guitarist.

Rather than the Biblical Satan, the devil in Tommy and Robert Johnson’s story is clearly more the trickster figure, the Eshu God as a guardian, the great inspirer who can make all things happen (W. Barlow). There is thus reason to see in the devil’s role in the blues of Tommy Johnson, Robert Johnson, and not to forget William Bunch, aka Peetie Wheatstraw, in the first place a reconfirmation of the African cultural legacy, and less an exponent of the Christian dichotomy between good and evil, between the sacred and the secular. Like the strong connection between dance and music, so was the devil in the blues largely a reminiscence of the older African tradition, dating back to slavery times, when the ring shout symbolized the unity of the daily life and the supernatural, and appealed to the “ultimate trickster” Eshu to take possession of the spirit of the dancers.

But, to conclude, I see, above all, in the enduring spirit of hope and optimism that is speaking in the blues and black music, despite the misery of the daily existence of which it is often a testimony, a continued affirmation of the legacy of the ring shout and the African cultural memory. The virtue of optimism and the tendency to set aside any possibility of despair for his destiny are without any doubt among the most eminent characteristics of the African way of life. When participating in the circle dance, the Africans realised at all time there was a potential for transformation and transcendence, and that change could be imminent. I see in this the reason why blues is not only sadness, but also, and perhaps most importantly, hope in survival and progress in spite of all life’s hardships.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Footnote:

(1) Click to : http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uxPU5517u8c

for a beautiful and inspiring footage on The McIntosh County Shouters performing Gullah-Geechee Ring Shout at a concert at the Library of Congress

Sources:

– Ayana Smith: Blues, criticism, and the signifying trickster, 2005

– Leslie M. Alexander, Walter C. Rucker: Encyclopedia of African American history, Volume 1, 2010

– Jonathan C. David: Together let us sweetly live: the singing and praying bands, 2007

– Mark Knowles: Tap roots: the early history of tap dancing, 2002

– James Weldon Johnson, John Rosamond Johnson: The books of American Negro spirituals, 2002

– John Shepherd et al (ed): Continuum Encyclopedia of popular music of the world

– Paul Finkelman: Encyclopedia of African American history, 1619-1895, 2006

– Elizabeth Calvert Fine, Soulstepping: African American step shows, 2007

– Albert J. Raboteau, Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South, 2004

– Allen Dwight Callahan: The talking book: African Americans and the Bible, 2006

– Henry H. Mitchell: Black church beginnings: the long-hidden realities of the first years, 2004

– Thomas DeFrantz: Dancing many drums: excavations in African American dance, 2001

– James Abbington: Readings in African American church music and worship, 2009

– Martha B. Katz-Hyman, Kym S. Rice: World of a Slave, 2010

– Melva Wilson Costen: In spirit and in truth: the music of African American worship, 2004

– Samuel Floyd, Ring Shout! Literary Studies, Historical Studies, and Black Music Inquiry, in: Black Music Research Journal 11(2), 1991, 265-287

– Samuel A. Floyd: The power of Black music, 1996

– Alton Hornsby: A companion to African American history, 2008

– J. William Harris: Society and Culture in the Slave South, 1992

– Melanie E. Bratcher: Words and songs of Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, and Nina Simone, 2007

– Colleen McDannell: Religions of the United States in Practice, Volume 1, Ch. 10, 2001 : Paul Harvey: African American Spirituals

– Lerone Bennett Jr.: Ebony, February 1971: The Making of America, Part VII, Of the Slave

– Katrina Hazzard-Donald: Hoodoo Religion and American Dance Traditions: Rethinking the Ring Shout, in: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol. 4, n° 6, September 2011

– Tera W. Hunter: To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors after the Civil War, 1998

– Lawrence W. Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom, 2007

– Jon Michael Spencer: Blues and Evil, 1993

– Sterling Stuckey: Slave Culture, 1988

– Harold Courlander: A Treasury of Afro-American Folklore: The Oral Literature, Traditions, Recollections, Legends, Tales, Songs, Religious Beliefs, Customs, Sayings and Humor of Peoples of African American Descent in the Americas, 2002

– Newbell Niles Puckett: Folk Beliefs of the Southern Negro, 1926