The reading of black music in America reveals a striking thematic continuity from the earliest slave songs to the blues and later to hip hop. One such a consistent theme is the expression of the emotional reaction from the individual singer, as the exponent of his group, to the oppression exercised by the dominant white social structure which excludes this group from participating in the social, economic and political centres of decision. In essence, slave songs, blues and later black genres as rap can be interpreted as different modes in which the black oppressed have dealt with the injustices imposed upon them by the system. In this article, I will illustrate this continuity in the historical line that can be drawn from the popular slave song “Run, nigger run”, via the banjo song “High Sheriff” performed by Dink Roberts to the Charley Patton’ song recorded in 1934: “High Sheriff Blues”. It will show how the appearance of the oppression changed, and how the nature of the reaction altered, but how finally this reaction stayed in essence an expression of the strong desire of the black population to stick to its dignity and remain faithful to its own cultural values.

I start the journey in Clayton, a small town in Alabama with a population of some 1.700 inhabitants, of which some 60 pct. are black or African American. Its history goes back to the arrival of the first settlers in the first half of the 19th century. When visiting the Clayton Baptist Church cemetery one cannot ignore the monument of the old town bell which has found on its grounds a resting place after having rendered service in the centre of town for over 100 years. For the black population, this monument rings a very special bell: in the antebellum days, the bell was also used to summon the “slave patrol” if any slaves were suspected of having run away (Dan T. Carter)

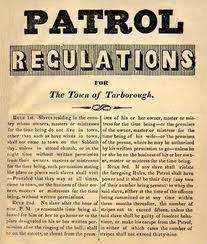

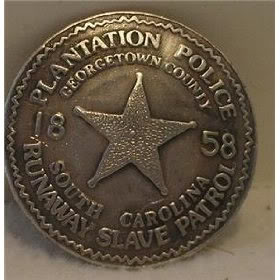

The ‘slave patrol’ or ‘patrollers’ were a private militia established to control the mobility of the slaves in order to prevent their insubordination and their running away. It was more than just a voluntary organisation set up by the slave owners; the institution of the slave patrols was enacted by law. In 1757 Georgia’s colonial assembly required for instance that white landowners and residents served as slave patrols. The Georgia legislature voted “An Act for Establishing and Regulating of Patrols” which was modelled on South Carolina’s earlier patrol law, and which ordered white adults to ride the roads at night. It was to stop all slaves they encountered and making them prove that they were engaged in lawful activities. The Slave Patrol required slaves to produce a pass, which stated their owner’s name as well as where and when they were allowed to be away from the plantation and for how long. The use of patrols, who could take up and bring to punishment ‘any negro or negroes that may be strolling about, not on their owner’s premises without a pass’ was widespread (Wilma King). They had the legal right to enter, without any warrant, the plantation grounds and often searched the slave quarters and inspected the slave cabins looking for anything that might be suspicious.

The plantation owner did not himself participate as a rule in the patrolling activities. Whites of means preferred not to serve on the watch (Wilma King); they hired substitutes to patrol for them: much of the burden of the patrol duty indeed fell to nonslaveholders, “who often resented what they sometimes saw as service to the planter class”. The slaves were well aware of this class distinction on the white side of society.

The patrollers served as the mould for the postbellum Ku Klux Klan which saw itself as the patriotic defender of law and morality, but actually was at the basis of the terror that reigned in the turbulent post war period. As such, the Klan was the new tool, replacing the slave patrol, by which the white community sought to control the activities of freedmen and freedwomen in the Reconstruction era. The tasks of the patrollers were also merged in later years with the modern day police force.

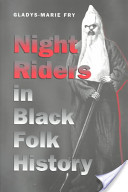

Gladys-Marie Fry (1975) demonstrates how both the Klan and the institution of the slave patrol were part of a system that was used by the whites, during and following the slavery period, of psychological pressure founded upon the fear of the supernatural that resided in the minds of the African American. The system aimed at discouraging the unauthorized movement of Blacks, especially at night, by making them afraid of encountering supernatural entities. It anchored itself in the cultural traditions that Blacks had brought along from Africa. Whites encouraged and adapted this African American’s belief in supernatural beings and turned it into a means for their psychological control. It is striking that the slave patrol system originated in the early practice observed during slavery when masters and overseers were riding around on the plantation dressed as ghosts. An interviewee in Fry’s study describes her grandmother’s account of an overseer riding through slave quarters covered with a white gown and with loud sounding tin cans tied to the tail of his horse in order to keep the slaves indoors at night. This image nurtured stories and beliefs in witches and ghosts that were menacing and intimidating the slaves when they left their place and moved around without permission.

These men were not surprisingly called the ‘Night Riders’ and would later – up until the 20th century – find their descendants in the ‘Night Doctors’ whose reputation was built upon rumors of doctors who roamed the streets at night to kill African Americans for use in dissections. The question remains whether it was only rumor without substance. I wonder. In her master’s thesis of 1997, Sarah Mitchell describes the influence that slavery had upon the evolution of the medical profession in 19th century America. Her account reads like a horror story. Since the (white) cultural context of the century considered dissecting as ‘degrading and sacrilegious’, cadavers for ‘hands-on-training’ and medical exercise were very hard to come by. At the same time, for the Africans, the very idea that a loved one’s body would be used for dissection was an extremely sinister thought. As a result, bodysnatching was a common practice, and the slaves being nothing more than ‘chattel property’ nothing stopped the medical students and professions from turning themselves in the first place to the “slave body” for experimentation and object of bloody study. Though the medical paradigm then considered the African American as a specific ‘species’, psychologically and physically (on the outside and inside) different from the white ‘race’, this thesis was not an obstacle for the medical world to rely quite exclusively on the black body (alive or dead) for testing theories and remedies. Medical Universities used their presence in the South as an advertising instrument showing the substantial advantage they had over their Northern colleagues because of the nearby presence of a pool of potential study material. In their analysis – framed in the context of the relation between race and medicine – of the bones found in the basement of the Georgia Medical College, Blakely and Harrington (1999) call the practice of abuse of the slave or black body for medicinal purposes a clear case of post mortem racism. Whether the story of African Americans being assaulted and killed in the name of medicine was factual or not, the very existence of the story had the same effect as the psychological terror exercised before by the ‘slave patrollers’.

How did the slaves digest this terror? How did they cope with the structural and permanent threat of dehumanisation? How were they able to survive in face of an oppressive system that denied them even the label of a being human?

One element of their defensive strategy consisted of the way that the slaves organised their daily activities and their family life as part of a larger web of social relations. This aspect has received relatively little attention so far but is promising to better understand the strategies that slave families devised within the larger community to help them endure the bondage. Slave families had structured themselves in a way that made their lives more bearable as beings who were trapped in bondage. It has been observed for instance that slaves deployed small scale economic activities around their cabin and outside of the control of the slaveholder. “Slaves not only consumed food taken or cultivated, they also sold or traded it, along with other goods and services, and used any cash they obtained to better their living conditions.” (Marie Jenkins Schwartz, 2001)

Next to this socio-economical defence shield, they also developed a cultural antidote, of which their internal communication was not the least important component. It is in this context that we can interpret the slave song “Run, Nigger, Run”, that appears to have been the most popular song of resistance that the slaves sang among themselves (Franklin).

In the Slave Songs of America, 1867, the song (n° 110) is coded as follows:

”O some tell me that a nigger won’t steal, But

I’v seen a nigger in my corn field; O

run, nigger, run, for the patrol will catch you, O

run, nigger, run, for ‘t is almost day”

There are different layers to the song.

In the first place, the song joins up with the common theme of “running” in slave narratives (theme of running away from slavery) (Dary Cumber Dance), a theme which will remain on the foreground throughout the Black literature in general in the following decades. Phyllis Klotman, founder of the Indiana University Black Film Archive and a professor emerita of Afro-American studies, has entitled her study of Black American literature: “Another Man Gone: The Black Runner in Afro-American literature”.

In a second layer, the song is obviously a form of oral communication which was functional to warn slaves of patrols on the hunt. It was the signal that the private militia was on its way to catch any slave that was on a place where he/she wasn’t supposed to be, or to check any goods in the cabins that were suspicious.

A third, more important aspect however, is its encoding of a certain perception of the slave patrol. As Wilma King illustrates, the song expressed more than just anxiety about armed men who planned to ‘git’ or ‘trick’ slaves. She quotes another version which runs as:

“Run, nigger, run patroler ‘ll ketch yer,

Hit yer thirty-nine times and sware ‘ didn’t tech yet.

Poor white out in de night

Hunting’ fer niggers wid all deir might

Dey don’ always ketch deir game

d’way we fool um is er shame.

I see a patteroler hin’ er tree

Tryin to ketch po’ little me.

I ups wid my foots an’ er way I run.

Dar by spiling dat genterman’s fun.”

The reference to ‘poor white out in de night’ can be explained in two different ways. Firstly, the slaves were well aware, as said earlier, that the patrollers were hired by the planter who did not prefer to do the job himself. He left it to other whites who were themselves nonslaveholders. Secondly, there is a solid dose of mockery in the song. The slaves fooled the nocturnal guards thereby spoiling ‘dat genterman’s fun’. The elusion of the patrol was celebrated by the song which can thus also be seen as a form of expression of pleasure, or – as Richard A. Long formulated it – as a form of robust humor that laughed at the dead patrollers.

Anyhow, the song was extremely popular then and it would remain so for a long time. As Norman R. Yetsman quotes from a slave narrative: “Dat one of the songs de slaves all knowed, and de children down on the ‘twenty acres’ used to sing it when dey were playing in the moonlight round de cabins in de quarters”. In 1940, seventy-five years after the end of slavery, the black children still sang the song whose upbeat tempo mocked the terror’ (Dan T. Carter). It is moreover remarkable that the tune in a variant title “Run, Boy, Run”, would become an old-time country music standard, recorded by fiddlers as Alexander “Eck” Robertson and by banjo-players as Uncle Dave Macon. ‘Run, nigger run’ was also part of the repertory of the Skillet Lickers, and old-time band from Georgia that provided Columbia its first ‘hill billy’ recording and which, together with fellow North Georgian Fiddlin’ John Carson made Atlanta and North Georgia an early centre of old-time string band music.

The song ‘Run, Nigger, Run’ remained however in its essence and its origin an instrument that testified of the daily struggle of an entire population with the oppression of a biracial society ‘based upon the foundation of unquestioning white supremacy” (Dan T. Carter). The strength and popularity of the song was nurtured by the original way in which a threat, a menace and the humiliation by dehumanisation were at the end of the day transformed into cheer and mockery and humor. It was part of the (psychological) survival strategy of the oppressed.

Then on January 1st 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation ordered by President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed the freedom of some 3.1 million of the nation’s 4 million slaves, and immediately freed 50,000 of them, with nearly all the rest freed as the Union armies advanced. The Proclamation was followed by the desperate effort to reconstruct what the Civil War had destroyed, politically and economically and to build a society in which the two races could co-exist without the one ‘owning’ the other. The question of full citizenship for the newly freed black population was on the top of the agenda. However, America was not yet prepared to face such an existential question. In the South the Blacks were now confronted with the same difficulty that their Northern fellows had confronted, being a free people surrounded by many hostile whites. As Houston Hartsfield Holloway, a freedman, wrote: “For we colored people did not know how to be free and the white people did not know how to have a free colored person about them.” The start looked promising. With the protection of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, African Americans enjoyed in the few years after the War a period when they were allowed to vote, actively participate in the political process, acquire the land of former owners, seek their own employment, and use public accommodations.

It was however of short duration. Opponents of this political and economic evolution soon rallied against the former slaves’ freedom and deployed every means to re-instore the control over the black population in another way than through slavery. The politics of “40 acres and a mule” which aimed at providing arable land to black former slaves failed, and slavery was replaced by another bondage system, in the form of tenancy and sharecropping. The iron chains were replaced by chains of debts and complete economic dependency.

The oppressive system of white supremacy changed faces from a slavery based structure to a society where political, social and economic segregation were legally enacted in Jim Crow laws. In a certain sense, the oppression was worse than before. During slavery times, the African American was – even if it was as a piece of property – still an integral part of the large society. The planter even considered himself, not only as the master, but also as the father of his slaves (which was in some cases to be taken biologically), a self-definition which was part of the ideology of total controllership over the black population. In the period after the slavery, the African American was no longer part of this society, on the contrary, he was thrown out of the white society in all its aspects, from the daily routine to the level of decision making. Jim Crow established a firm barbed wire around the white society to protect it from black intervention. The blacks were supposed to build their own society, with no readily available model that was suited to their specificity and which could inspire them in their shaping of an own social structure.

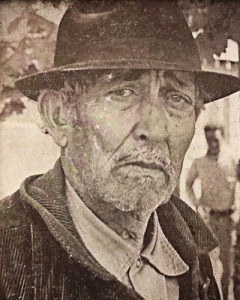

In all its simplicity the one stanza song ‘High Sheriff’ by Dink Roberts – a black banjo player in the Appalachian Mountains, born at the end of the 19th century – gives a painful and sorrowful summary of this feeling. The end phrase: “What’s gonna ‘come of me?” sends the shivers through my spines each time I read or hear the song:

“Well ah

High Sheriff and police

riding after me

What’s gonna ‘come of me

Yeah,

down the street a-coming (2x)

dwon the street a-coming Monday morning

Well ah

What’s gonne ‘come of me?”

While in ‘Run, Nigger, Run” there was an appeal to flee from the danger that was coming along in the form of the slave patrol, the performer now expresses his woeful despair about the fate that the new society has come to reserve to him: “What’s gonna ‘come of me?”. The slave patrol has now taken the form of the ‘High Sheriff’ who is ‘riding after’ him. There is not longer a cry to run away, but an existential questioning of the place that the singer has in face of the menace. There is now uncertainty, fear, a clear, deep emotional response to the threat.

The High Sheriff is a representative, not any more of the former white slaveowner, but of the new legal system that the white ruling social group has constructed to control the other racial group, or better to exclude it all together from their society by means of harsh segregation rules. In this sense, the uncertainty and fear that Dink Roberts puts in this poignant question ‘What’s gonna ‘come of me?’ is also the anguish of the black population: it is the dramatizing of a universal condition of entrapment and dread (C. Conway). The singer’s own point of view and experiences symbolizes the anxiety of the African American’s in the face of the threat of a white social structure in “the form of one its contemporary representatives, the sheriff.”

Yet, ‘High Sherif’ and ‘Run, Nigger, Run’ have in common the durable desire of the oppressed black to maintain their dignity in the face of the denial by the ruling class of even the basic social and human rights. Whilst in ‘Run, Nigger, Run’ the warning hid a clear mockery and humorous expression, ‘High Sheriff’ is a reflection of an individual, in the name of a group, upon his social position with a clear consciousness of his own sense of values and eminence.

This strive for dignity, and thus for self-preservation is thus a striking element of continuity that leads from the early slave songs until the black repertory still performed in the 19th and 20th century. C. Conway, justly, pays a great deal of attention to the repertory of Dink Roberts in her majestic study on the African roots of the banjo in Appalachia. She has extensively documented the work of Dink Roberts and a number of his contemporaries. Her study argues that the black banjo songs of artists such as Roberts were a distinct musical genre “governed by its own African-American aesthetic standards”. Roberts is considered to be a link with Afro-American traditions and his repertory is for Conway a striking example of what she defines as a distinct musical genre: the banjo song. I will not explore any further here the dimensions by which she defines this genre since this would lead us too far in the context of the topic we are here addressing. What is relevant here is the textual characteristic: one of the themes of the banjo song is the one which opposes the singer to the law. Thematically, says Conway, the banjo songs reveal the historical context pervading in the Upper South, showing the concerns in the lives of the black folk at the turn of the 20th century. The slave patrol as a repressive tool in the hands of the patriarchal planter had been replaced by the ‘sheriff’, the law which was now the antagonist in the songs. ‘The man-against-the-law’ theme is a recurrent one that is speaking of a central character who does ‘not fully control his own destinty’. The protagonist in the song is a vulnerable person that is threatened by the law of the dominant society and who fears being captured, confined and even put to death.

At the same time, Conway further argues, the banjo song, of which ‘High Sheriff’ is an illustration, continues to support the singer who appeals to the community which tries to maintain its values in resistance to the threat of the oppressive law. It is an emotional cry to the social group, not to one or another divine person. The banjo-song is thus a secular musical genre that sets it apart from the other black genre, the spiritual.

The documentation put forth by Conway offers support also for an earlier thesis developed by Robert Winslow Gordon a main figure in the study of American folk song – he was the founding head of the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress in 1928 – that a particular group of banjo songs may prove to be important forerunners of the blues. This is of course most interesting food for thought and further debate. Though the matter is evidently much more complicated, the thematic continuity that ran further to the blues from the early slave song over the banjo song pleads indeed in favour of this thesis. ‘Run, Nigger, Run’ and ‘High Sheriff’ describe the response of a particular person and group to the social structure to the life pattern of oppression that he faces on a daily basis. Both songs are ‘not a collection of facts, but an emotional and creative expression, () a guide for facing the harshness of social reality’ (Conway, 278).

The Blues would later on be another form of expression, in an even more assertive way, of the same type of concerns of the black population with their place in a more and more industrialized society that however still denied it the rights that were denied to their ancestors.

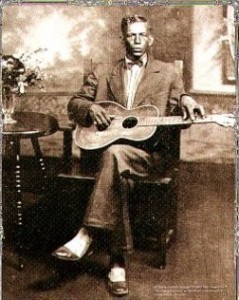

Charley Patton’s ‘Tom Rushen Blues’, re-recorded in 1934 as ‘High Sheriff Blues’ serves as an example of this assertive expression of a theme that portrays the life of the common black man in face of the injustices of the Southern law.

Get in trouble at Belzoni, there ain’t no use a-screamin’ and cryin’

Get in trouble in Belzoni, there ain’t no use a-screamin’ and cryin’Mr. Will will take you, back to Belzoni jailhouse flyin’

Le’ me tell you folksies, how he treated me

Le’ me tell you folksies, how he treated meAn’ he put me in a cellar, just as dark as it could be

There I laid one evenin’, Mr. Purvis was standin’ ’round

There I laid one evenin’, Mr. Purvis was standin’ ’roundMr. Purvis told Mr. Will to, let poor Charley down

It takes booze and blues, Lord, to carry me through

Takes booze and blues, Lord, to carry me throughBut it did seem like years, in a jailhouse where there is no boo’

I got up one mornin’, feelin’ awe, hmm

I got up one mornin’, feelin’ mighty bad, hmmAn’ it might not a-been them Belzoni jail I had

(spoken: Blues I had, boys)

While I was in trouble, ain’t no use a-screamin’

When I was in prison, it ain’t no use a-screamin and cryin’Mr. Purvis the onliest man could, ease that pain of mine

As it was the case in ‘Run, Nigger, Run’ there is an outside and inside layer to the song. On the first reading, the song narrates a personal experience of Charley Patton who has been jailed for drunkenness in Belzoni, a city in the Mississippi Delta Region, on the Yazoo river (in ‘Tom Rushen Blues’ the jailing in Merigold is the subject of his song). Patton was not only popular with women and had married several times, he was also fond of drinking liquor and his tendency to be argumentative made him several times the protagonist in the ‘struggle with law’ and made him a client of the jailhouse.

But there is more under this outside layer than this autobiographical story. It is also an observational song that tells us about the power that is exerted by the white over the black, represented here not by the slave-owner or the ‘High Sheriff’, but by small-town Mississippi law enforcement. Charley Patton commented directly and extensively on contemporary public events, witnessed or experienced, or on threatening events in his own life. Perhaps, he was also the first recorded black folk artist who mentioned white people from his own community in his songs in an unfavourable way.

We observe, as in Dink Roberts’ “High Sheriff” the ‘man-against-the-law’ is again the theme wherein the antagonist, the unjust and racial Southern Law, is now personified in petty law officers. While being a very personal expression (Patton misses for instance the ‘booze’ in jail), it is also a lament about the hopelessness of being put on trial in Belzoni and the inevitability of a conviction there (Peter O.E. Bekker).

The social context had changed from an agrarian society to a fully industrialized one. Also the entertainment context had altered. Whilst Dink Roberts and his contemporaries had played foremost in the local context of family, friends and nearby frolics, Charley Patton was an archetype of the professional musician that toured from place to place within an institutionalized context of juke joints. More than a more love for the music, this career decision to heave his family environment – which by the way was not that unfavourable for Patton compared to other early (blues) artists – was at the same time a political statement of non-acceptance of the ruling social expectation that blacks were supposed to run behind the mule to pay off their debts to the white. Even if his individual songs are not necessarily always a form of social protest, his life choice testified of a rejection of the social norms, and a confirmation of the own identity and dignity, as did blues in general.

The popular slave song “Run, Nigger, Run” laughed at the white planter; Roberts’ “High Sheriff” raised a fundamental question about the place of the black in the Reconstruction and post Reconstruction society; “High Sheriff Blues” continues to question the justice of the Southern law through the personal life experience of the singer in which however all of his black contemporaries of the lower social class could all too easily recognize themselves. The “Night Riders” were no longer the talk of town, but they were still very much present, be it in another form. It was no longer the terror of the white man, dressed in a white gown, riding in the night on his horse looking for possible runaway slaves, or the threat of the body snatcher searching for “slave bodies” that constituted the terror in the 20th century. It was the whole legal, economic and political structure that entrapped the black population, the same one which would later be both origin and target of the hip hop that developed amongst the marginalized youngster in the Bronx in New York.

If we take it further, even the image of the “Night Riders” had not completely faded in recent times. When between 1979 and 1981 twenty-nine young African Americans disappeared in Georgia and of whom twenty-eight were found dead – a case which rose broad national media attention and even made the president come down to Atlanta – the image of the ‘Night Riders’ popped up again. The persistence of the nightmare proofed that the social conditions that had fuelled its initial genesis continued to foster its survival.

_____________________________________

SOURCES

______________________________________

– http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-900

– http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/aaohtml/exhibit/aopart5.html

– http://undercoverblackman.blogspot.com/2007/09/run-n-gger-run.html

– http://ttexshexes.blogspot.com/2010/10/charley-patton-biography-part-1-dr.html

– http://gagen.i-found-it.net/gacrime.html

– Cecelia Conway, African Banjo Echoes in Appalachia: A study of Folk Traditions, 1995

– J.W. Harris, Deep South: Delta, Piedmont, and Sea Island Society in the age of Segregation, 2001

- Dan T. Carter, The Politics of Rage, 2000

– Norman R. Yetman, 100 Authentic Slave Narratives, Voices from Slavery, 1999

– Richard A. Long, Afro-American Writing: An Anthology of prose and poetry, 1985

– Osha Gray Davidson, The Best of Enemies: Race and Redemption in the New South, 2007

– Marie Jenkins Schwartz, Family Life in the Slave Quarters: Survival Strategies, in: Magazine of History, Family History, vol 15, n° 4, Summer 2001

– D. Cumber Dance, Long Gone: The Mecklenberg Six and the theme Escape in Black Folklore, 1989

– Wilma King, Stolen Childhood: Slave Youth in 19th century America, 1998

– Robert L. Blakely, Judith M. Harrington, Bones in the Basement: Postmortem racism in Nineteenth-Century Medical Training, 1999

– Gladies-Marie Fry, Night Riders in Black Folk History, 1975

– Vincent P. Franklin, Black self-determination: a cultural history of the faith of the fathers, 1984

– Sarah Mitchel, Bodies of knowledge: the influence of Slaves on the Antebellum community, 1997

– Alabama, a guide to the deep South, , Writers’ Program of the Work Project Administration in the State of Alabama, – R.R. Smith, 1941

We’ve had discussions about Lawrence Gellert’s “Negro Songs Of Protest” before. Even though his political views were pretty radical, he did capture the essence of your paper. Please forgive the words of this song, but it was typical of the 30’s.

You take mah labor

An’ steal mah time

Give me ol’ dish pan

An’ a lousy dime

‘Cause I’m a nigger, dat’s why

White man, white man

Sit in de shade

Heah in de hot sun

I sweat wid his spade

‘Cause I’m a nigger, dat’s why

I feel it comin’, Cap’n

Goin’ see you in Goddamn

Take mah pick an’ shovel

Bury you in Debbil’s lan’

‘Cause I’m a nigger dat’s why

(“Cause I’m a Nigger”)

——————–

Call him drunken Ira Hayes

He won’t answer anymore

Not the whiskey drinkin’ Indian

Nor the Marine that went to war

Yeah, call him drunken Ira Hayes

But his land is just as dry

And his ghost is lyin’ thirsty

In the ditch where Ira died

Didn’t see anyplace written the Tom Rushen/High Sheriff is a song based on Booze and Blues rec earlier by Ma Rainey and that the lyrics are of a true story the man in the story was interviewed by Gayle Dean Wardlow. This should be considered IMO in any analysis. This was a good article but I still keep in mind that lyrics can mean something much different than what one might conclude…