Blind James Campbell, Blind Blake, Blind Jim Brewer, Blind John Davis, Blind Boy Fuller, Blind Arvella Gray, Blind Joe Hill, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blind Tom Wiggins, Blind Willie Johnson, Blind Willie McTell, Blind Joe Reynolds, Blind Joe Taggar, Blind Willie Walker, Blind Blake. What do these men have in common? They are all Afro-Americans musicians whose visual impairment doubtlessly contributed to an extra dimension in their musical genius. For some of them, music was also the only way to make a living given their visual handicap.

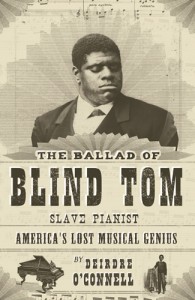

One of them however does not fit completely in the list since he was in the classical music and not in the blues-folk realm: Blind Tom Wiggins, aka Thomas Greene Bethune.

Let’s go some 160 years back in time.

In a number of European countries, 1848 had witnessed the start of a series of revolutions that were fuelled by a widespread dissatisfaction with the ruling political class, the demand for more democracy, the social claims of the working classes and an upsurge of nationalism. Tens of thousands of people were killed and many more were forced into exile.

In the Northern colonies of America a major relocation of the slave population to the deeper South had taken place in the wake of the invention of the cotton gin that had made the culture of cotton significantly more profitable. Tobacco remained an important cash crop in Virginia, but due to depletion of the soil, other crops grew in importance and tobacco plantations shifted more to the west. In Georgia, rice cultivation – more profitable than tobacco – was at its peak, underpinned by the presence of the African Americans: there was a near identity between black labour and white rice. Few crops are more demanding to cultivate than rice, particularly “wet” rice. The cultivation requirements were arduous and the mortality rates in the mosquito-infested swamps were very high. Rice culture was only possible thanks to the slavery.

In 1850 the American Congress enacted the Fugitive Slave Act, maintaining a firm grip in the Southern counties on the institution of slavery, so much needed for the agricultural sector. The new law, much to the dissatisfaction of the abolitionists, gave free rein to pursue fugitive slaves in any state and return them to their owners. No limitations were applied, so that even those slaves who had been free for many years could be (and were in fact) returned. The Nat Turner’s slave rebellion of 1831 had sent a shock wave through the white population leading to stricter new legislation on the activities allowed by slaves.

In this same time frame, the multiplication of camp meetings testified of the Second Great Awakening and a rapid increase in the popularity of various Protestant denominations, especially Methodists and Baptists. The indifference that plantation holders in the British colonies had shown in the 18th century towards the religious and in general, towards the cultural patterns of their slaves, made place in the 19th century for an attitude first of tolerance and then of participation in the active promotion of the Christianization among their working force. “People saw and confessed that slaves were made better by religion” (Epstein, 2003: 197). During those meetings, black and white – though each population occupied its proper section of the camp – worshipped and sang hymns together, sometimes in gatherings of 3 to 4.000 participants. “The singing (of the slaves) was inspiring and was encouraged and enjoyed by the white congregation, who would sometimes remain silent to listen””.

During the last decades before the Emancipation, the banjo, the fiddle, bones and quills had become major instruments in the musical activity of the slaves. Dancing to the music of the banjo had become a commonplace. The banjo was considered as the real musical instrument of the Southern Negroes. Also the black fiddler had become a familiar image. “Some had homemade fiddles, and others, store-bought ones, but most were encouraged by their masters to play for the dancing of their fellow slaves, as well as for white visitors or dancing parties. In the rural South the slave fiddler seems to have been a necessary support to dancing and other recreations.” (Epstein, 2003: 149).

Together with an increasing number of converted slaves grew also the opposition to secular music and dancing, though some planters tolerated it – within the conditions they defined – because it maintained the ‘good spirit’ and contributed to the general diligence. Nevertheless, the Great Awakening brought along an antagonism between secular music and dancing on the one hand and evangelical religion on the other hand. This juxtaposition was never seen in the African culture in which the secular and the sacred were all part of one reality.

Very little to nothing is known about the tunes the slave musicians played. We can only guess. It is known however that a number of slaves were able to come to the foreground out of the anonymity of slavery, and were hired by their masters for parties and enjoyed a reputation that extended (far) beyond the boundaries of the plantation. Some documents also describe the musical education of a slave being promoted by his master. One example is that of slave Robin, property of Manning, Governor of South Carolina during 1852-1854.

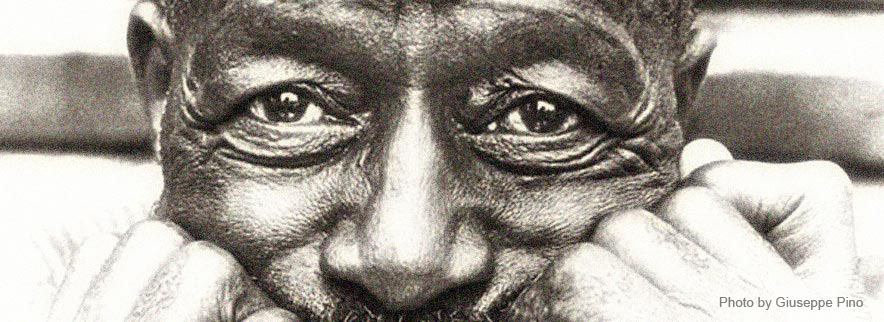

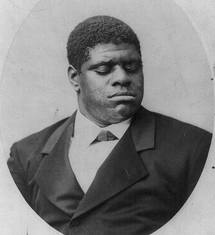

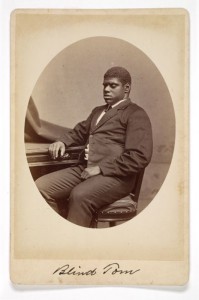

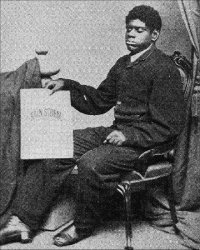

It is in this historical context that on May 25th 1849 on the plantation of Wiley Edward Jones in Harris County, Georgia, Tom Wiggins is born, another slave whose reputation would not only grow beyond the plantation but would finally stretch nearly around the world. Born blind, his life span went from the slave auction block over concerts in America and in Europe to his death at age 59 from cerebral apoplexy in the apartment of his guardian of that time, Eliza Bethune, in Hoboken, New Jersey.

Blind Tom Wiggins was born into slavery as the twelfth (some sources say fourteenth) child. His master Wiley Edward Jones was not very keen on clothing and feeding a disabled ‘runt’ and wanted the infant dead. If it were not for the vigilance of his mother, Charity, Tom would indeed not have survived. At the age of nine months old, master Jones put the baby, his two older sisters and parents up for auction, intending to sell the family off individually and not as a unit. The chances of anyone buying a blind child were next to none: his death was as good as certain since a blind child was of no value at all.

Tom’s life was spared again thanks to the tenacity of his mother. A few weeks before the auction, she approached a neighbour, General James Bethune, and begged him to save her family from the auction block. At first he refused, but on the day of the sale, Bethune turned up at the slave market and purchased the family. Tom was included in the sale “for nothing”. Following the traditions he got the name of his new master: Thomas Greene Bethune. His master James Bethune, also lawyer, was known as the first ultra secessionist and the first radical free trade Democrat. He was also the first newspaper editor in the south to openly advocate secession. He was thus not immediately the man who saw his slaves as entitled to much freedom.

On the Bethune plantation, Tom saw him nevertheless granted the liberty to roam the rooms of the mansion while his mother worked as a house slave. It was obvious from the beginning that the boy was fascinated with sounds of all types, which he imitated, and most of all with music. He seized every occasion to listen to the master’s seven musically talented children who overflowed the house with their singing and their piano sonatas and minuets. Until the age 5 or 6 years he could not speak, scarce walk, and gave no other signs of intelligence than this everlasting thirst for music. But, already at the age of 4, when he could take place at the piano he astounded the family when his small hands and fingers seemed able to reproduce the sequence of chords from his memory exactly the way he had heard them.

James Bethune told Tom’s mother that the infant had as much intelligence as the family dog and he consequently he began to teach Tom as if it was his pet and to make him respond to animal commands like “sit” and “stand.”

At the end of the day however, master Bethune had to recognize the presence of a musical prodigy in the raggedy slave child. He installed him in the mansion and started an extensive tuition. One of Tom’s teachers would later report that the child could learn skills in a few hours that required other musicians years to perfect. It is said that he learned Beethoven’s 3rd Concerto to perfection in just an afternoon.

When he was six, Tom was already performing throughout Georgia. He was promoted as an ‘untutored’, ‘natural’ musician who could repeat any composition, no matter how difficult, after a single hearing. Two years later, Tom was licensed out to a travelling showman who promoted him “as a real Barnum-styled freak”. The newspapers routinely compared him to a baboon, trusty dog or hulking bear. However, the public was time after time astounded. The deal made by Bethune with the showman was extremely lucrative: estimates are that Bethune pocketed $15,000 from the arrangement and that Tom’s manager made profits amounting to $50,000. As for Tom, he was separated from his family and was exhibited throughout hundreds of cities on a rigorous four-shows-per-day schedule.

In 1860, he was the first African-American to give a command performance at the White House before President James Buchanan. By October 1862, Tom was back with the Bethunes who continued to use his talents for the pro-slavery cause: he was made to giving concerts in the South for Confederate soldiers and raising money for the Southern cause. Tom was of course not aware of the political abuse that was made of him. For him, only sounds mattered and he didn’t realise that he served as a propaganda tool for the political agenda of his master.

Emancipation failed to free Tom from the shackles of slavery. General Bethune was realistic enough to foresee that the South would fall to Union domination, and as a lawyer it was not too difficult for him to arrange a contract giving him management of Tom until he reached the age of twenty-one. In exchange, Tom would receive food, shelter, musical instruction and an allowance of a mere $20 a month. Bethune would retain over ninety percent of the remaining profits from Tom’s performances; conservative estimates indicate an amount of at least $18,000 a year.

Tom never knew he was free because he had never actually known he was a Negro slave. He was launched upon tour after tour bringing him to Great Britain, Scotland, Canada, the Rocky Mountain states, the far West, and South America. His repertoire included up to 7,000 pieces with approximately one hundred of his own composition. It contained many of the most technically and musically demanding works of Bach, Chopin, Liszt, Beethoven and other European masters. Meanwhile, he had added also the French horn and flute to his list of instruments that he mastered. Concert stages, hotel rooms, and train rides were his life, leaving his social capacities totally undeveloped. He had his meals in seclusion and needed help to dress him before appearing onstage.

Behind his back a juridical battle was fought over his custody, or call it: over his ‘ownership’. When Tom turned twenty-one and his indentured contract ended, General Bethune requested, with success, that the courts declare Tom legally insane and appoint himself as his legal guardian.

I will refrain from going into the details of the custody fights in several courts that followed and took several years bringing his fate at a certain moment in the hand of the General’s son who continued to exploit Tom’s talents only to finance his own luxury life style.

“Blind Tom’s final years were shrouded in secrecy and paranoia” (Deirdre O’Connell). He spent them as a ward of the ex-wife of James Bethune’s son John and her husband, who divided their time between New York City and New Jersey. In 1903 Tom started to appear on the popular vaudeville circuit wherein he remained for almost a year before his health began to deteriorate. In April 1908 he suffered a stroke and in June that year he died at the apartment of his guardian in Hoboken, New Jersey. Some time before Tom was already kept out of public view. Only neighbours could enjoy Tom’s piano playing at all hours of the day and night.

With our present knowledge we now understand that Tom had the savant syndrome, a very rare condition in which people with developmental disorders display one or more areas of expertise or brilliance that stand in contrast with their overall limitations, frequently also autism. It leads people with this syndrome to try to assimilate all the sensory information that comes to them from all over, which may result with many to engage in repetitive behaviour to deflect the overload. Music seems to have offered Tom this type of escape. Behind the piano, the splintering effects of autism – the sensory overload and fragmented perception – disappeared and Tom was able to experience a sense of integration: moments he clearly savoured and his inspired outpourings of joy impressed many who witnessed him.” (Deirdre O’Connell)

Within his time however, Tom’s extreme talent was tainted by the deep-rooted racism. He was presented as ‘an idiot’, a state which was continuously confused with the widespread belief that Africans were closer to the animal kingdom than Europeans. The opinion was that he was gifted with some ‘second sight’ which allowed him to communicate with spirits somewhere in another world. His extraordinary powers and bizarre behaviour were seen by some through the prism of race by some as supernatural. The latter defined him as a medium that channelled the music of the great masters, while the former insisted that his compulsive urge to move around constantly and his “natural” musicality were intrinsic expressions of his “African-ness.”

Whatever the view, he was denied his humanity and has been exploited all of his life. Even if managed to stand out of the anonymous crowd of slaves by his extra-ordinary talent as a musician, he continued to undergo the faith of a slave, even after the Emancipation. His life story, how exceptional it may be, is at the same time illustrative of the time spirit and racism that reigned the 19th century. It lifts somewhat the veil on how life was then, which is the reason why I felt it useful to share this story with you, even if there is no direct link with the blues.

If you are eager to listen to Tom Wiggins’ compositions, go and look for John Davis’ CD (not to be confused with Blind John Davis!): John Davis Plays Blind Tom, Newport Classic, 85660 (1999).

____________________________________________

SOURCES

____________________________________________

http://blindtom.org/

http://www.twainquotes.com/archangels.html

http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/bethune/bethune.html

http://chevalierdesaintgeorges.homestead.com/wiggins.html

http://encyclopedia.jrank.org/articles/pages/887/Bethune-Green-Thomas.html

http://www.wisconsinmedicalsociety.org/savant_syndrome/savant_profiles/tom_bethune