Abstract:

The article aims at gathering some of the statements and arguments in the over debated question on the balance of the European and African cultural elements in the blues. It finds that the different positions in the debate bear a remarkable resemblance to two theoretical schools in the cultural anthropology, namely the cultural evolutionist approach and the contextual approach (cultural ecology). A number of explanations are put forth why the debate persists. The author is not optimistic as to the probability of a substantial progress in the debate, unless emphasis in research shifts towards a more inclusive perspective instead of the dominant fragmentary view. In particular, the need is felt for more comparative studies which would offer elements against which the findings related to the blues could be articulated. This leads the author in the margin to the inevitable question why only the vernacular ‘bluesy’ African American music has succeeded in influencing western popular music but not other vernacular ‘bluesy’ genres as tango or fado.

—————————————————————————————————————-—

Is it the blues in life which has given or gives rise to the blues in music?

A simple question, which I believe most of us – including myself – will spontaneously affirm. And, yet, it deserves a closer inspection. If at the end of reading this article you agree with me that a simple affirmation is probably a bit too simplistic, then I consider my mission as accomplished. I will have succeeded in sharing with you the flavor of some of the many questions I have been struggling with lately as it were from ‘can to can’t’. But beware, before reading any further, there are more questions than answers. Don’t blame it on me when you are left more puzzled at the end than what you are now.

My original intention of the article was to shortly describe the magnificence of the joyous events that took place in the 18th century and the first decades of the 19th century on the “Place de Nègres”, in New Orleans, a place commonly known as the “Congo Square”. Slaves gathered there on Sunday not only to sing and dance in their style, but also to organize a market for goods they were allowed to sell. The Congo Square was on Sundays bubbling over with life, contrasting sharply with the more restrained activities on the Sabbatical day on the northern plantations of Virginia and Carolina. In a later article, I intend to come back on the Congo Square which even today inspires artists not only in America (see the “Congo Square theatre” in Chicago), but all over the world (“Congo Square” is e.g. also as a company formed in the winter of 2002 to promote jazz and blues in India).

F.W. Evans has very recently published the results of her research during more than 15 years on the Congo Square. On the cover of the book I read comments as : “The bloodlines of all important modern American music can be traced to Congo Square”, and the “Congo Square is iconic in African American history. The music and the dance of the gathering place transformed the art forms of this country”. I can subscribe to the importance of the magnificent work that F.W. Evans has accomplished to give us more insight in this major cultural monument in American cultural history. However, we need to put the Congo Square in a broader perspective to comprehend and evaluate its full significance. It brings us ultimately to the question of and how the forced migration of 0.5 million Africans has influenced American music. If we accept that blues and its immediate relative, jazz, has influenced modern musical history – and there are arguments enough to support this assertion – then how and to which extent can we trace back the blues to its slaves antecedents? Are the bloodlines completely traceable or has blood been altered significantly during its lines of genealogy?

I believe that we should in the first place be clear that there is no generally agreed definition of blues music. From a musical point of view, the genre can be described in terms of its emphasis on (poly-) rhythm, percussion, anti-phony, polyphony,… But as soon as such a definition is given, examples can be put forth of songs which do not fit the general criteria. Since I am a layman on this domain, I will limit myself here to referring to the Encyclopedia of the Blues edited by Komara (2006: 105-110) which contains further references. It is also illustrative to look at the many attempts that have been made to pigeonhole the various past and actual styles in the blues.

In cultural-historical terms the matter is not easier, on the contrary. It would be limitative to study the blues in terms of a single, linear historical line that starts with slavery up to the first documented observations of blues by Jelly Roll Morton, Charles Peabody, Ma Rainey or W.C. Handy. The fact that the debate on this ‘line’ is heavily burdened with ideological positions doesn’t make it any simpler. It is a small step from raising questions about the degree of purity of the African element in the historical blood line of blues to getting involved in a fierce political and emotional debate about ethnic issues. All cultural dimensions are in fine linked to their social-economic and political context, including music, but there are only few musical genres that are so closely linked to their social context than blues, and that are so much susceptible to creating a vigorous discussion. The comparison is probably a bit unfortunate, but I feel that emotions in the discussion on the nature and origin of blues are often as fierce as when fans of different football teams meet. Don’t get me wrong: this debate is inspiring. It is also fully comprehensible since at the end of the day the arguments that are put forth by the parties are related to their self-definition as member of a particular social group. Discussing the blues is discussing about one’s soul as it is related to the group to which one belongs. It is also a very democratic debate in which all social strata can participate: from the academic to the musician, from the well to do business man to the man or women who has to fight each day to make ends meet. Emotional arguments are often as valid as empirical evidence, which at the end of the day need a theoretical frame to gain meaning.

I do not want to take a position in this debate in what follows, only to understand and to position it in a larger context. It was for me refreshing to realize that the “roots debate” can be brought down, in general terms, to two different approaches that also exist in the cultural anthropology. Cultural anthropology is a branch of anthropology – i.e. study of humanity – that focuses on the study of cultural variation in societies and that collects data about the impact of global economic and political processes on local cultural realities.

One such an approach posits that human beings share a set of characteristics and modes of thinking that go beyond, that transcend individual cultures. It attempts to describe and to explain long-term changes in human ways of life. The term “cultural evolution” is used for specifying a focus on long-term changes not in properties of a social group as such (e.g., its sheer size or location), but in the way of life – the characteristic artifacts, behaviors, and ideas – of the group. This theory which primarily centers on continuity, on what unites the present with the past is called the cultural evolutionist approach.

In another approach, denominated as cultural ecology, the cultural change is seen as the result of adaptive processes in response to the specific context and characteristics of the local environment at a particular point in time. The cultural ecology will more than the evolutionist approach focus on the correlation between a particular environment and the culture which it creates. Cultural ecology emphasizes that the specific characteristic of a environment (region or time period) plays a significant role in shaping the culture of its population. It stresses the contextual element of cultural evolution.

With some simplification one could compare those approaches to the “nature versus nurture” debate which is one of the oldest issues in psychology: what is the relative contribution of genetic inheritance versus environmental factors to human development?

With this distinction in mind I have collected a limited sample of statements on the history of blues and black music that come from different sources, going from academic studies to forum discussions on the Web. I then labeled each relevant statement whether it expressed an evolutionist or a cultural “ecological” approach. A number of statements, a minority, steered a middle course. Under here, I give a short overview of the statements. Sometimes they are literally quoted (without referring however to the author), sometimes textual adaptations have been applied to make them more comprehensible and readable within the present context.

The cultural evolutionist approach

– The history of the American Negro is the history of the strife and the longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self (an American and a Negro) into a truer and better self. This dual identity is a dominant theme in the Afro-American experience, which is reflected in his politics, religion and his music.

– It is the African resistance to total acculturation that produced a hybrid culture known as African-American. By accepting certain attributes of the master’s culture which were essential to their survival or congenial to their past learning, and clinging to those aspects of the African culture to which they found no satisfactory substitute, the Africans cut a niche for themselves in a predominantly white society.

– The lives of all black people in America have been fundamentally shaped by the racial experience of slavery; the memory of enforced servitude in the past has molded attitudes and feelings in the present and has conditioned the black American’s stance in the world. Since the end of slavery, the black communities have been searching for their identities in relation to white culture, in relation to themselves and in relation to their past.

– It is not definitely known when blacks began to mix European and African musical practices, however it has been observed that Afro-American musical style had emerged by the beginning of the 19th century. This was basically African in concept, a social, communal and functional music with a repertory of religious songs, work songs, satirical songs, insult and ridicule songs, street cries, ballads and many more which were suited to their context. This confirms the historical connection between African and Afro-American music.

– In fact musicologists may quibble about where some particular scalar, harmonic, or tonal characteristic of the blues came from; they may debate the twelve-bar form, the shuffle beat, etc. But there’s no denying that the blues “event” itself, at its core, represents a ritual of ecstatic abandon with distinctly African roots: a venerable tradition in which spirit and flesh mingled closely together; in which dance, rhythm, melody, and prayer interwove into a single celebration.

– The idea of a white blues singer seems an even more violent contradiction of terms than the idea of a middle-class blues singer.

– I don’t subscribe to the “European Roots of Blues” school; those roots are marginal at best, should be mentioned as there are some, but everything is turned upside down.

– The Blues represents the true and authentic feeling of Afro-American music. The blues was sung with such emotional intensity that was peculiar to only the African who shared the slave experience. You have got to be black to feel the blues. There is no blues without the slave experience. To be blue is to sing the blues. The blues as a means of expressing life’s experiences suggests that it is the blues in life that gave birth to the blues in music.

– It makes me wonder what makes one think it is legitimate that European when migrated to other places took their heritage, culture and arts with them, but the Africans when migrated were always coming up empty, no culture.

– The functionality and the contextual relevance of African music, an essential heritage of the Afro-American, ensured the continuity of a rich African musical tradition in the Diaspora.

– Having identified the roots of Afro-American music as essentially African, it is important to stress that, over the years, there has been a steady cross-current of musical ideas and cultural exchanges between Africa and the Diaspora.

– The contributions of African Americans to our cultural fabric in this country have long been understated. To think that the blues had its origins in a Mississippi Delta cotton field ignores the cultural contributions that hundreds of thousands of native West Africans brought with them even though they were forced slaves. The simple fact is, if slavery had not existed in the 16th and 17th century, the music we call the blues would not exist today. I can’t dismiss the influences that European music, especially Celtic music, had in creating this music we call the blues. There’s no doubt that the Celtic musical scale and European instruments played a big part in developing what became blues music, but the heart of the blues will always be African.

– Afro-American music, though re-defined to reflect the realities of the American environment, retains essential African elements till date. These core African elements like rhythm, blue note, dance orientation and a whole gamut of performance practices buttress the point that Negro music making in the USA has an essentially African core. One can safely advocate that Afro-American music is to be seen as the continuation of the African tradition in the Diaspora.

– The African tradition is still alive in the Mississippi hills. The closest to the original African sound can still be heard in the fife and drum bands that play in that area.

– Certainly the blues, like jazz, is an amalgamation of many cultural and ethnic influences. Nonetheless, it needs to be stressed that – at least during most of its existence as a living and evolving musical form – the blues has represented a Black “voice.” Like so-called “Black English,” that “voice” is infinitely varied, and contains multitudes, but there is something deeply and vitally African-American about the identity it assumes.

– The blues have absorbed influences and “voices” from diverse sources and influences; yet blues have established and retained a particular “ethnic” – for want of a better term – voice/identity for which they are highly valued.

– The blues came from Africa, not from some cotton field in the Mississippi Delta.

– The blues had a baby and they named it Rock and Roll, because the blues came from African soul.

– It is at least arguable that, as some may state, there was no “blues movement,” as such, in the ’20s and ’30s. There certainly was, however, an “African-American vernacular music movement” (for want of a better term). It covered the gamut from unrecorded “folk” music (work songs, field hollers, etc.) through hymns and religious songs, acoustic blues, “classic” blues, all the way to jazz, pop, and beyond. The observation that Robert Johnson sang pop tunes is beside the point; his “voice” was a Black voice, and thus he was a part of this “movement” no matter what he sang. And certainly his recordings – whether he himself labeled them as “blues,” or whether that name was given to them by the record company – represented a Black voice, strongly and eloquently.

– Musicologists seem to agree that the twelve-bar form basically represents an individualization of the call-and-response. The individual serves as both “caller” and “respondent,” in other words.

– There is strong evidence that slaves held their very own clandestine services, away from the eyes of white overseers. These were strongly “Africanist” in both form and content, even as (over time) they incorporated more and more elements of Christian theology.

– Their music was (and is) African-American in its essence; it did (and does) retain strong core African elements in both its melodic/rhythmic forms and the way(s) in which it manifested in performance; and it did (and does) represent a voice of resistance (although not necessarily “political”) and cultural/historical identity/pride.

– What seems to be happening as the music evolves and the old blues masters fade from the scene is that a ‘revisionist’ approach to the roots of the music is emerging. Influences that previously played only a contributory part in a musical pot-pourri are now apparently sufficiently important to, if not deny authorship of the music to African-Americans, then severely denigrate their contribution. Justifying such an approach requires harder evidence than what is available now.

– Many examples from slave narratives, from interviews with former slaves, from the writings of white observers who attempted to document the slave culture in its natural habitat show how African cultural practices, including discourse styles and the spiritual/social mores that they represented, were retained and adapted to life and struggle in antebellum African-American society. Theorists have shown how these elements of the oral tradition were adapted, and continue to be utilized by poets, novelists, and essayists writing in the African-American literary tradition.

– While the blues is certainly grounded in a broader constituency today, saying that the African-American fabric so basic to its origin and essence is irrelevant now is not only ignorance, but sometimes a form of attempted theft. It would be hypocritical to say whites aren’t entitled to love, advocate or play the blues, I’m just saying that those upon whose backs the music was built deserve to have their contribution recognized and acknowledged as a lasting basic of the music and not be consigned to ancient history or academia.

– I don’t believe Black American music adopts the tonality or tuning structures of first generation white European emigrants; there is too much proof to the contrary.

– It is always interesting that when one debates the origins of the blues one always ends up looking at scales and harmonies. That’s such a European way of looking at the music! I have always found the link to African music to be in the rhythm and the lack of conventional Western harmony. Harmony as we understand it – chord progressions – is a very unusual thing by world music standards. Most cultures, including most African cultures, tend to just stick on the I. With blues, this is the clearest link to Africa. Listen to such widely different blues singers like Charley Patton, Sonny Terry and Blind Willie McTell. You can sing the melody and keep full harmony without ever changing chords. Now that’s African.

The contextual approach (cultural ecology)

– There is doubtless a connection between West African music and the blues, but it gets overstated and the impact of the folk and religious music of the British Isles is understated, and still more so the creative achievements of the first blues men and women.

– As Christianity was forced upon the slaves, European, mostly Celtic hymns became assimilated into the music that was becoming the blues. Celtic scales are almost the same notation as what evolved into the blues scale. All of these ingredients began to shape what we call the blues today.

– Nothing proves that the blues “came from Africa.” Black people came from Africa, and they brought their music along with it, but after several hundred years, that music evolved, taking various forms at different times, blues being just one permutation, and a late development at that. The blues certainly would not have happened without blacks and the tradition of African music, but neither would it have happened without white people and European musical influences.

– I would never argue that blues could exist without black people, or African influence, but that is not the same thing as saying “the blues came from Africa.”

– I think that trying to reduce a modern, innovative art form created (in part) by black people who had lived in this country for 300 years, to a vestige of tribal music that blues’ practitioners were unfamiliar with (even if they retained many aspects of it) is undermining their contribution.

– Blues is American music, like ragtime, country, R&B, rock and roll, rap, etc

– I would not deny that blues is a black or African-American music, but I think that to say it “came from Africa” is misleading.

– It is still unclear how much “blues” is a folk music or a folk adaptation of popular music.

– There was no “blues movement” during the 20s and early 30s. There were songsters who were as likely to play ragtime songs, gospel songs, and ballads as blues. We also have to remember that blues was primarily dance music, and the connotation that the word has now was not necessarily the same as it was before.

– I don’t think that blues or anything that the songsters were doing in the 20s and 30s was self-consciously African or black. I think that a lot of the music is marked by black characteristics, but of course, there are also recordings where we can’t tell if the musician is white or black, which is a telling reminder of the musical climate of the time.

– Blues is a relatively modern form of music with hazy origins that has as much western influence as African influence (and I don’t just mean European influence; I mean that the blacks who helped create blues were as African-American as the blacks who created jazz, although there are definitely some cultural and geographical differences). The blacks who created blues were most likely playing ragtime pieces before they were playing blues, and in many cases they learned blues from records (“pop” records, no less) as much as they did around the plantations.

– Certainly the music in the 20s and 30s was called “the blues” by then; but it does, indeed, seem very questionable (to say the least) whether Patton, House, Johnson, et al. called themselves “blues singers” or “bluesmen” on a regular basis.

– Segregated slaves were often in close contact with whites as part of their daily work. They cleaned the master’s house, they made his bed and worked in his kitchen, they nursed his babies. They served as “waitstaff” for balls, parties, and, no doubt, other occasions where music was played (whether that be “folk” music in the Anglo-Celtic tradition, or European “classical” music, or pop music of the time). And, let us not forget, the initiative to convert slaves to Christianity began very early on – which, of course, was an extremely significant element in the cross-cultural exchange.

– Southern segregation did not mean that people weren’t physically proximate to one another. “White” and “Black” areas/neighborhoods/communities were often adjacent to one another; people saw, heard, and experienced at least some aspects of each other’s’ cultures on a daily basis, even if they technically weren’t allowed to interact as equals (or even at all). Sociologists have long noted that so-called “lower”-class people usually know a lot more about the lives, culture, and ways of their “upper”-class counterparts, than vice versa. And, the cross-cultural exchange went both ways.

– The 12-bar form is an interesting question: there seems to be a fair amount of evidence in support of the hypothesis that the 12-bar became standardized only in the 20th century. Transcriptions of African American songs from the 19th century look quite a lot like blues, except for the fact that there is no clear 12-bar form, and no standardized repetition of the first line before the “response.” There is even a possibility that the standardization of the 12-bar form came from Tin Pan Alley.

– Vaudeville-style music – and its cousins in traveling tent shows, medicine shows, minstrel revues, etc.- dates back a lot farther. Maybe there is an under-recognized influence here? And maybe, as well, it might account for at least some of the similarities across regions?

– We know that on at least some plantations, slave minstrels entertained whites at parties – meaning, obviously, that they had learned to make music that sounded “good” to European ears. Maybe they were expressly trained in this; maybe, as savvy and expert musicians, they picked up on these “foreign” styles on their own. But well before Emancipation, European musical influences had worked their way into the music of African-born (and the descendants of African-born) slaves in the Southern U.S.

– As far as resisting the influence of Christianity is concerned, my understanding is that most African religions are very open-minded in terms of dogma: they are very “oecumenical” in their outlook, in other words, they have historically adapted ideas, beliefs, even actual deities from other religions which they have come into contact with.

– I don’t think the blues does or has ever sounded particularly African; what does sound African are some (not all) of the indigenous music forms of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Haiti, and the West Indian (including coastal South and Central American) nations. Compared to the Black Puerto Rican, Cuban and Haitian music, the blues does not sound the least bit African.

– Why do all the white people want to imagine they hear African sounds in the Blues? The blues was made in America by (African) Americans in America. It seems like the African slaves were cut off from the African cultural influences much more so than were the African slaves in the nations in and peripheral to the Caribbean. The only thing African about the blues is the African descent of those who originated the blues.

– The decade of 1880 also saw Blacks take on a greater role in minstrelsy, but not in all regions. Blacks started to play roles which were previously handled by whites in black-face. This would show both command and acclimatization of the idiom from a performance standpoint.

– The two methods of making music – African and Scots-Irish – were in a stylistic sympathy. This does not mean that they were co-equal, but only that simplistic dichotomies as European/African do not really work. They fail to give credit to the white influences on expression and global aesthetic, and they reduce the African American influence to something of a noble savagery, ignoring the use of harmony and more sophisticated techniques derived from more formal kinds of training.

– Black music has always been marked by the idea of an imaginary Africa, a reference which helped white critics to acknowledge the musical inventiveness of slaves by the mid-19th century without disturbing racial prejudices too much.

– What makes everyone believe that a socially, physically, and mentally oppressed community was able, or even wished to, keep and develop a concealed, distinctive musical genre, or type of singing? This is pure projection of the colonialist ideology on African-Americans, as if they were an independent and united nation with its own codes, language, and religion, likely to ignore and dodge the overwhelming cultural oppression. What was left of, or had evolved from African traditions for centuries, was not allowed to become part of a mode of expression, or even considered as of any aesthetic value by African-Americans themselves, until the new, fashionable, urban trend called “blues” in piano rolls and early sheet music spread all over the rural South at the beginning of the 20th century, giving the music some fresh air and granting local entertainers the right and encouragement to “sing’em the way they felt”.

Do we not need to consider the birth of the blues as a historical event?

– It makes sense that as the slaves got their names from the slave masters and that they carried the slave owner’s blood, their religion and their customs, that they should have adopted and adapted their music.

– Technological progress and mixing of cultural groups tend to be the main catalysts in the birth, cultivation and evolution of genres.

– New music and new cultural dialogues are made within the context and the possibilities provided by existing social relations, technological means and aesthetic conventions.

– Social influences are crucial to the blues: most blues singers were exposed to the existing work songs and religious expression early in life and were able to adapt some of the melodic character, subject matter, emotional intensity, and spiritual depth to the developing of the blues. There are thus important antecedents to the blues that bypass the influence of African culture.

– Although many academics agree that the blues may hold an ancient oral tradition, it is also true that the majority of its content was a personal and communal response to the changing patterns of repression and powerlessness among the poorest segments of the South Eastern black society rather than a continuation of an established historical tradition.

– Blues is a form of musical expression, rather than a long historical tradition. The genre is a perfect receptacle for external influences.

– Musical innovations are the result of commercial opportunities for individual genius, entrepreneurs who recognize the new demands and act to meet them.

– The publishing of the blues genre was a process of consolidation, with definitions of the style beginning to appear, and given a name by the appearance of published tunes bearing the word blues in their titles.

– It can be said that the blues was born from geographical factors (the African Diaspora and slave trade, southern labor), nurtured and developed within the afflictions of an oppressive society and economic volatility, and was eventually stabilized by the consolidation of its politics.

– Ties with Africa persisted in the memories of slaves who had been born in the British colonies, and the memories they handed down to their children. However, the Europeanization of the mainland slaves was irreversible.

– Just as the need for communication weakened the position of African languages, so in music and dancing European elements crept in, little by little. Except in isolated communities of runaway slaves, the process of acculturation was unavoidable.

– Things in the blues had come from the tribal musicians (in W. Africa) of the old kingdoms, but as a style the blues represented something else. It was essentially a new kind of song that had begun with the new life in the American South.

The middle approach

– The term “blues” is probably way too limiting to describe/invoke the rich and varied (and still living/evolving) musical heritage. Perhaps, ultimately, “African-American Diasporan music” is closer to the right term.

– It is generally acknowledged that the music was at heart an integral part of African American culture. This seems to be challenged now without – as far as I can see – any real supporting evidence. I can understand why people would like the Blues to be called American music but I don’t understand why they would want to diminish the influence of its African American creators. Surely the two are not mutually incompatible?

– It’s not an “either”/”or” discussion. One can be both “rootsy” and also be new or even iconoclastic in one’s own innovations. One can tweak, elaborate on, even mock what’s gone before as a tribute to it, not in disrespect of it. Indeed, it’s the highest sign of respect to plant one’s own individual identity on something that a great master has done before. These tweakings / elaborations carry with them important essences of the original inspiration, but the end product is something new and different.

– The dichotomy between being a “purist” and being an “innovator” is a western concept, and has done great harm to a lot of things, the blues being only one. The very idea that a “canon” or a “repertory” exists in some kind of historic isolation, to be venerated and reproduced note-for-note or word-for-word, is the antithesis of the African notion of honoring the ones who’ve gone before by improvising on their creations and creating them anew.

– To succeed, music must be an invocation of life in the present tense, an emotional (and often physical) call to action, not an artifact. Roots are strong only when they nurture something that is alive and growing.

– Cause and effect are by now buried that it is hard to determine how much effect whites had on blacks.

– I don’t agree that African music had little or no influence on the blues. It had a huge impact. But I also disagree that European music had little influence on the blues and that it’s only marginal. Blues simply wouldn’t exist without the contribution of white music, just as Bluegrass wouldn’t exist without the contribution of black music.

– Blues emerged from a melting pot where the predominant ingredient derived from Africa but was augmented by many different cultural influences.

What can we conclude?

As I stated above, I do not want to take a position in this discussion in the present article which only aim it is to try to comprehend and to posit the arguments. I will thus phrase my conclusions in the form of raising another question: why does this debate between what I called the evolutionist and contextual approach continue so intensely (in an explicit and an implicit way)?

The reasons are multiple and are in itself an interesting topic for a long exchange of views. There are three grounds though that seem to me of major importance: (1) the definition of the blues, (2) the quality and quantity of the available historical material and (3) the way this material is approached.

1. Definition of the blues

One could write a book collecting and analyzing the many definitions of the blues. The very ambiguity of the definition is debit to the continuing debate on the origins and development of the musical genre. If there is no agreement on what we are talking about (not from a musical perspective, nor from a cultural perspective), then there is also no way of reconciling the positions. If it is questioned whether or not the key players on the blues scene in the 20s and 30s defined themselves as blues artists or not, I’m completely lost. If I notice that today artists are booked in blues festivals but do not consider themselves as blues performers, there is manifestly a problem of denomination.

I am afraid though that the efforts for a better mapping out of the genre will also end up in the same discussion as outlined above. What anyone sees as the blues is as culturally determined as the way that he sees its historical evolution. It goes without explanation that ethnic elements will sneak into what is seen as blues or not, especially when the topic is raised of what is considered as authentic or not.

Perhaps, I would suggest, it is not necessarily appropriate to come up with too strict a definition, since, after all, we would never succeed in doing justice to the extremely rich variation in musical expressions which receive the blues label. The possibility to bring forth most individual variation on basically simple chords is by the way one of the characteristics of the blues. Too strong an attempts at categorizing would moreover mislead us just the same way as when the blues was first being ‘codified’ on sheet music and then on wax. Putting in pigeonholes complex phenomena relaxes the mind and leads us to the false feeling that we have a good overview of the situation, but leads even more to a withering of the infinite richness of reality.

2. The quality and quantity of the material.

The further we go back in time, the more rare the material on which suppositions and theories need to be based. From what I have understood so far, the documents which are available and relevant for what concerns us here are relatively scarce for the period before the Emancipation, and especially before 1800. This is a crucial period when the first intercultural exchanges began. We can only conjecture as far as the sounds are concerned, of course, and even if our speculations seem safe in view of some incidental detailed documents at our disposal, the first obligation is to remain critical about the sources and to ‘read’ them in full abstraction from our own historical biased views. Let us also not forget that people take notice in the first place of what attracts their attention, of what seems ‘odd’ and ‘weird’. Sometimes, the absence of historical observations and documents sounds harder than the presence of them. Moreover, the available documentation needs to be interpreted in its past social context, with the bulk of the material being produced by the ‘ruling white’. The ideological stand of the observer was no less important. An example: from a religious point of view, dancing was for instance seen as sinful and was likely to be either ignored or to be the subject of fierce condemnations. Abolitionists would also prefer not to mention slaves dancing as this was seen as in contradiction with the image of the suffering slave; slaveholders, on the contrary liked to promote the image of the dancing slave as it was the ultimate confirmation that slaves were a happy bunch.

True, a rich source of documentation comes from the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), organized within the framework of the “Works Progress Administration” (WPA), a New Deal program set up by president Roosevelt in the 30s. Between 1936 to 1938, more than 2.300 former slaves from across the American South were interviewed by writers and journalists. These former slaves of whom most were born in the last years of the slave regime or during the Civil War, provided first-hand accounts of their experiences on plantations, in cities, and on small farms. Without any doubt, their narratives constitute an extremely important resource for understanding the lives of the slaves and the texture of their daily life, including music. But, also with this source, do I need to repeat it, extreme prudence is at the order of the day.

What goes for the documentation on the American context bears even stronger validity for the African sources. The acknowledgement that there was a cultural diversity in the background of the hundreds of thousands of slaves that were brought to the colonies in the north – some directly from (West) Africa, some indirectly through the West Indies – is already a first prerequisite for a serious analysis.

3. The approach of the material

More than the ambiguity in the definition of the subject and more than the absence of (researched) material and documentation of sufficient quality, the nature of the approach to the material and available data is for me a key explaining factor for the persistence of what often seems an endless discussion. Very often the assumptions (academic and non-academic) are based on fragmentary data or a personal interpretation of sonic resemblances which are extrapolated at a higher, general level. Observations made for a particular population or time period lead far too often to non-justified generalizations about larger populations or time periods.

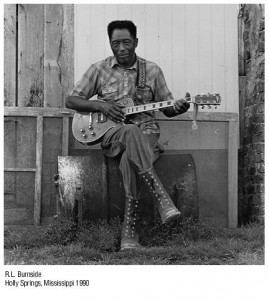

By way of illustration: one could be tempted to interpret the music of Otha Turner or from Sid Hemphill, as a sign that the African tradition is still alive in the Mississippi Hills. Alan Lomax had understandably a keen interest in this music when he recorded it in 1942 and later in 1959. In his article on Otha Turner in “Bluesnotes, May 2003”, G. Johnson, states: ”Fife and drum bands have their roots firmly planted in African music. Long traditions carried over by captured slaves, brought to American soil where their new owners attempted to quell the sound, especially in the South. They kept the music alive in their memories and passed them down through the generations.”

The need for a nuance in this general (evolutionist) statement is obvious when, as fieldwork by a.o. David Evan (1972) has shown that the fife and drum tradition is more widespread than the earliest research demonstrated. It can be suggested that as early as the seventeenth century blacks may have “picked up” the skills of fife or drum playing from the militia units in New England and the Middle Colonies, since in the early decades slaves were compelled to undergo military training. The author continues stating that the early accounts might indicate that black fife and drum bands were modeled on and did not differ considerably from their white counter parts, qualifying it however by adding that there is a possible influence of black music on the early military fife and drum bands.

Another illustration where falling in the trap of too quick a generalization is also very real is offered by the discussion on the emergence of the Negro spirituals and more particularly the link between the African American hymns and their European counterparts (lined out hymn singing). Willie Ruff has unearthed that some remote African American congregations in the Deep South and some white congregations in remote churches of Appalachia sang hymns in Gaelic, and linked this back to an ancient call-and-response service still intoned in Gaelic in the highlands of Scotland. After his initial findings, he extended the syncretism to practices of some Native Americans pointing thus to a unique mix of Gaelic, African and American native cultural elements.

However, is this complete story? Probably not: was it the English or the Gaelic tradition that impacted the lined out hymn singing? As a friend suggested me recently on a forum: “The evidence is not particularly strong in the Gaelic direction. Lined out hymn singing wasn’t even exclusively British in origin, as it can also be found amongst the Amish from a German language tradition (it’s pretty doubtful the Amish hymn singing had any important impact on the slaves).”

These two examples show that an exclusive approach based on fragmentary data is particularly dangerous and can lead to theories that start to live their own life – especially in an era where information spreads so quickly and so widely – and that are at the end of the day taken for granted without examining their original sources.

Especially in a field with so few definite and tangible data available, an inclusive approach is mandatory. Each statement should be carefully weighed against as much data as possible coming particularly from comparative research. The latter should not be limited to the sole African American population but could be broadened to the total African Diaspora. There are examples of broad comparative studies. Roger Bastide has for instance studied African influences throughout the Americas. He found much stronger African influences in Central America and the Caribbean than in the USA, with the exception of two main centers: Sea Islands (Virginia coastal area) and the region around New Orleans.

The historical evolution of slavery in each county and country as it is expressed in a particular development of social, economic and demographic variables seems to me crucial for an understanding of how black music has evolved. Birth and death rates amongst the slavery population, for instance, have had a clear impact on the need for bringing over new slaves from Africa and thus indirect on the persistence and survival of African cultural idioms. These demographic data on its turn depended upon the type of plantation and labor systems that were in place, etc….

But do we need to confine ourselves to just blues or black music? The findings related to the development of blues and black music could be articulated against findings which result from global models including other musical genres. One such a model worth considering still is the one founded by Victor Grauer and Alan Lomax who developed the cantometrics method which attempts to relate regularities of musical style (or musical organization) to social organization and also to historical factors. It establishes correlations between easily observable style factors and elements of class stratification, gender relations and sexual value systems. This method has been taken up again very recently by Armand Leroi, an evolutionary biologist with the Imperial College in London. Leroi is testing the ability of computers to analyze sound in view of creating a Cantometric description of traditional music from various cultures.

Another interesting path for investigation might be the comparison between the emergence of African American blues and other “bluesy” genres as the tango in Argentinia, the fado of Portugal and the Greek rebetica. As Mark A. Humprhey (1993) contended: “Blues wasn’t the only folk music to emerge in the nineteenth century that spoke plainly of the pleasures and pains of a poor underclass”. Tango, fado and rebetico “all grew from urban subcultures and voiced the taboo, sex, drink, drugs”. They have each been “called the blues of their respective countries, in part for a quality of musical mournfulness, but more importantly for their vivid descriptions of a life style that, by polite standards, was deemed scandalous.” These genres also stemmed from a blending of different working class cultures. Tango is said to have been born out of a.o. African, Italian, French and Spanish influences. The Greek blues, Rebetico, developed around ports and urban centres starting in the end of the 19th century and blossomed on the arrival of a stream of immigrants pouring in from the Greek Isles and from Turkey. Its lyrics are most often melancholic and deal with the hardship of uprooted people, the missed love ones and the dramas of the working man’s life. Fado is also characterized by mournful tunes and lyrics, often about the sea or the life of the poor. One theory on its emergence contends that the Fado came to Portugal, also a crossroad for cultures, by the music of the Brazilian slaves.

If the vernacular musical genre that we label the blues and that emerged in the South of the United States has been able at the end of the day to “catch the attention of the world” and has influenced significantly today’s popular music – in contrast to other local genres – we inevitably have to ask if other than its intrinsic qualities are relevant. I would suggest an affirmative answer. We cannot ignore the role that the United States have played in the world politics and in the fostering of its culture and language all over the globe. Already in the 1910’s the dominant record companies emphasized music as a product for export and started establishing branches all over the world. It was only with the start of World War I that they felt the need to look for expanding the markets in the homeland as the European consumer had other things on his mind. It was no coincidence that the race market was promoted just after World War I: it was a much-needed commercial boost for falling sales abroad.

And, oh irony, it was the former motherland that taught the former colonists in the sixties that Muddy Waters was not a lake in the USA but a precious jewel on the crown of their very own cultural legacy.

As a blues lover we have to be constantly aware to see the object of our love in a proper perspective and to step out of what I might call a tunnel vision. This perspective can only make our love deeper. What continues to make blues for me so special, next to its musical qualities, is its merger of the ‘I’ and the ‘WE’, the fusion between the artist and its audience. There is so little distance between performer and listener. A friend, blues musician, once trusted me that he was constantly amazed how helpful blues lovers are between each other as a world community. Isn’t that special?

And for the musical qualities, let us remember the words of Victoria Spivey: “To pay too much heed to standardized blues tones and bars spoils the emotional impact inwardly for yourself. You must feel in your heart most of all, not in your brains or in the interest of your pocket. Flat tones, whether they be hard or soft, show the freedom in blues singing. You should never know when they come out of you. The heart will tell the voice when.”

To conclude, let me come back to my initial question: Is it the blues in life which has given or gives rise to the blues in music? From my side, I feel better equipped now to answer it.

This is a very interesting article, and clearly lots of research went into it. I think the two groups of theorizing (evolutionist vs. contextualist) is helpful to navigate the intense debates. I’d also add a similar grouping between “identity politics” and, say, a more “materialist” approach. The identity politics aspect seems closer to the evolutionists, and the contextualist is closer to a more materialist analysis. If I had to side with one, I’d say i’m closer in my own understanding of blues (even though I’m not a researcher of the blues, and basically only a player and listener) to the contextual group. What irks me about both sides (at least through your own narrative of both sides) is that both sides prefer not to look more deeply at the connections between slave society in America and post-slave society in America. What mediates both is the history of capitalism in the world and especially in 19th century America. And as you pointed out, one of the most signficant things about early 20th century american culture is that it had a clear “internal” colonial dimension in the area of sound recording, where “negroes” were captured on tape, much in the same way that colonial anthropologists photographed natives in colonial territories. But to say that recording was a fundamental “context” in which we could first imagine and know what blues is, as an object of knowledge, is also to say that we couldn’t ever know anything about the blues if it weren’t for the expansion of capitalist commodities,including recording artists’ records. I think it’s telling that this kind of analysis is almost obsessively cut out of debates on the origins of the blues because it implicates all of us in trans-racial ways. It’s precisely this trans-raciality of the blues as a commodity that I think a lot of people don’t want to deal with, precisely because it displaces a notion of any origin of blues as an ethnic question to a more economic one. But frankly, the economic one is more objective to me. I’m rambling now, but thanks for your work, you got me thinking.