The history of the United States flows largely in the riverbed of the relationship between the white and the African American population. The way in which those ethnic groups have interacted since colonization fills the main chapters of the book on the development of this nation. As a student of the emergence of the blues the reading of those chapters is thus mandatory. However, it seems difficult for many a student to conduct this reading of what can be called the “race-issue” in the genesis of the blues without implicitly or explicitly expressing social-political opinions. This is understandable and natural, but it tends to give rise to a biased interpretation and it creates the risk to stand in the way of a full understanding of historic facts. Many a discussion even quickly takes an emotional direction which then completely obscures the debate.

I do not plead innocence in this matter; my personal views can easily be read between the lines in my previous articles. At the same time however, I continue to feel the need (fed by my background as sociologist) to develop a framework which allows me to approach the emergence of blues in a more objective way which lets the facts speak as they are (if this is possible). In this framework, the race-issue is of course an aspect which in no way can be ignored, but I consider it as only one of the angles from which the blues in her full meaning and significance can and need to be considered.

What follows is my first attempt in building this framework. I acknowledge that it is incomplete, and that it will need to be checked and detailed by further study. Perhaps, I even took a wrong direction and I will need to change over later as my insights grow. Within the context of this article, I also need to stay on a very general level. However, I believe that for the moment the main elements of the framework are already capable of offering support for the comprehension of many observations in a more socio-political neutral way. At least, they helped me to interpret data in such a perspective.

Throughout this exercise, I admit, I felt the handicap of the absence of a musical background and therefore I count heavily upon feedback from musicians reading this article to fill the gaps in the model.

In this model, I understand that a musical performer can be defined according to some key dimensions, which are:

a) the way by which musical skills are/have been acquired

b) the (broadness of the) repertoire

c) the degree of integration with the audience/public

d) the degree of autonomy.

The musical performers of the pre blues and early blues period in the Southern States can be positioned on each of those dimensions. The musical evolution over time or sometimes also throughout the lifetime of a particular performer can be depicted in terms of the movements on each of those dimensions.

Let me explain all this in what follows, concentrating mainly on what happened on the scene of the ‘popular’ music in the last half of the 19th century and in the beginning of the 1900s. Following this general introduction, I will then try to come to a more detailed profile sketch of the early blues performer according to those dimensions.

Let me explain all this in what follows, concentrating mainly on what happened on the scene of the ‘popular’ music in the last half of the 19th century and in the beginning of the 1900s. Following this general introduction, I will then try to come to a more detailed profile sketch of the early blues performer according to those dimensions.

a) The acquisition mode of musical skills

The question here is: how did an artist develop his (her) musical skills? Was there an involvement of formal schooling and learning, next to hard practice and (self) study?

It is a well known fact that (early) blues artists and their ascendants developed their musical techniques in the ‘school of life’. Most if not all of them started already as a child to develop interest in music, stimulated by the musical background of their relatives or neighbours. Hearing them play at home or at social events was the input for the youngster to cultivate his own talents. “Self-taught” is a word that constantly pops up in most of the biographies of those early musicians, and it would even be foolish to try to quote examples of biographies here.

At first perhaps limited to family and neighbours, the sources for the acquisition of skills expanded over time with the increasing mobility during the second half of the century. The accruing density of the railroad network went hand in hand with a higher level of mobility of the musicians, sustaining the popularity of touring groups and performers. This allowed the learning musician to pick up techniques from visiting performers but also to travel himself to picnics, parties or other social events at ever further distances where he could learn from other musicians he admired.

The advent of the records at the end of the century augmented further the learning sources. Live performances were complemented with waxed material as the inspiration for learning (new) techniques, tunes and lyrics. The phonograph became widespread – let us not forget the role played by mail order companies here – and assured that music could spread around much faster than before. The possibility to replay a record over and over again was of course a luxury that could only contribute to the refining of the technical skill of the zealous student.

There are legends which let us believe that some artists acquired their skills from a bargain with the devil. But that is a totally different story; if this type of devil would exist the world would not look the same.

b) The (broadness of the) repertoire

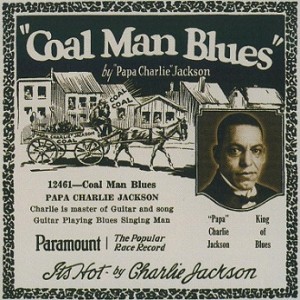

In his in-depth study, “Segregating Sounds”, Miller (2010) strongly highlights the variety of the repertoire of the early blues artist and his ascendant. Even when the blues became an ever increasing part of the musical repertoire, other popular songs remained on the list of the performer. At the risk of too strong a generalization, one could say that the average musician included a substantial part of European inspired music in his performance acts. I refer to ballads, polkas, waltzes, marches…The second half of the 1800s also witnessed the rising distribution of tunes produced in New York City by the famous Tin Pan Alley-collection of music publishers and writers. Mail order companies helped the spread of the Tin Pan Alley sheet music in the Southern States, which was further sustained by touring (vaudeville) theatres (often orchestrated from New York City) and medicine groups.

Whilst in the first decades of the 1800’s the nostalgic black face minstrelsy – eulogizing the supposedly perfect social harmony during slavery times – dominated the scene, the coon song – which stripped to its purest form the burlesque and stereotyped image of the African American citizen – became top of the pops by the end of the century. This song became the guarantee of success, next to Tin Pan Alley-products.

Blues may thus in the late 1800s, early 1900s, have become an increasingly important part of the musical offering – thanks also to the popularity of the slow drag dance – most of the artists continued to have an eclectic approach to their musical offering and embraced a quite wide range of genres to attract the public.

c) The degree of integration with the audience/public

The distance between the performer and his audience is in my opinion an essential characteristic in the typology. In this I refer to both the audience that is present during a live performance, as to the record buying public.

During a live performance, it is of course vital that a performer reaches out directly to his audience. Contrary to classical music, which demands foremost a technical perfect and if possible an individual interpretation and translation of an existing composition, the success of a popular performance depends upon the sustained feedback between performer and audience. The closer the distance between them (not merely in the physical meaning of the word), the more the success is guaranteed.

In the case of the blues for instance, the interaction between the musician and his public is as crucial as the song itself. One can even wonder whether it is not even more crucial than the pure tune and lyrics. A blues song is not written on paper, it comes to life when it is nurtured by the input of the public. Its shaping takes places when an individual performance style is enriched with the mood of the one who listens to it. The artist’s and public’s mood feed each other to become, at each new successive performance, a new song, never heard of before. Blues are not only born out of and in reaction to a particular social context, they depend for their survival on the public which lends the song each time a new meaning.

The distance between a performer and its record buying public is another aspect, which is however less evident to observe or to measure. The introduction of the recording technology and its media for distribution added a totally new dimension to the relation between a performer and his public. Very broadly spoken, one can observe an evolution from a situation where the popularity of a performer depended exclusively on his ability to appeal directly to a physically present audience, to a situation (starting at the end of the 1900s) where his popularity was also based on the distribution of his product by an increasing complex array of intermediary bodies. The live performance of a song in itself was no longer sufficient to obtain success.

And what is more: the art of live performance is quite different from the skills that are required in a recording studio. I think we cannot imagine ourselves enough the psychological earthquake that it must have caused for those early artists to go into a studio and perform for a big wall with a horn (later replaced by cool microphones). One can find examples of artists who ‘froze’ when they needed to play. Also, it has been observed that in an early stage, the artists who were invited by the record companies to produce the cylinders and discs did not necessarily perform live (William Howland Kenney, 2003). Especially the early technology imposed upon the voice and the instruments other requirements than those needed during a live performance. The sensibility and accuracy of the early recording techniques were far away from what they have become later.

The integration between performer and public is closely linked to the next dimension: to which degree can a performer manage this integration himself, and how far can he manage his own career?

d) The degree of autonomy.

Though today the recording technology is more and more ‘democratized’, especially with the spread of digital media – which opens more possibilities for artists themselves to publish their recordings, and thus take more control of their own musical destiny – the technological evolution which started as from the late 1900s lead to a fundamental existential difference for the artist before and after this evolution. Again at the risk of generalizing too much, one could contend that the recording business and the radio were a straightforward attack on the autonomy of the artist. The more technology was introduced, the greater the gap between the artist and his pubic, the less the former had the capacity to manage his own musical fate. Technology is expensive and requires capital which is by definition scarce.

There is a huge difference between the very first American musical business of the black face minstrelsy and the situation which arose when media companies as Edison, Victor and Columbia came to dominate the market in the early 1910s, later joined by a series of other record companies. The radio and the establishment of national broadcasting networks added another complexity. There is by the way an irony in this evolution: the more (technical) possibilities the artists had (indirectly) at his disposal to obtain success at the national (and international) level, the less possibilities he had to steer himself the direction of this success.

At this moment we make abstraction of the ethnic aspect that pops up when one looks at the ownership of this increased technological context. I will come back on this later. Let us stick for the moment to the neutral observation that there was a striking evolution in the complexity of the intermediary bodies that positioned themselves between the artists on the one hand, and the public/listener on the other hand. This observation is valid for both the distribution of the material means of a performance (record, radio) as for the decisions related to and the management of the live performances. A potential broader audience came clearly at the expense of the substitution of the autonomy by a delegation of power to other bodies (most often with non-artistic objectives) to reach this audience. There is no such thing as a free lunch.

+ + + + + + + + + + +

So, where does the definition of those dimensions leads us in the comprehension of the place and role of the early blues artists? How can we define him in the historical context using the above dimensions?

I am convinced that it is beneficial to view the early blues artist in the first place as a professional. The stereotype of the early blues musician is that of a romantic, wandering performer, busking, and playing his guitar for a street audience or for a noisy dancing or gambling public in a juke joint. This stereotype only corresponds to part of the reality. It is more realistic to view this musician as a fully fledged entertainer who had made a clear choice on how to conduct his further live and how to make a living. We don’t need to consider the fact that earning money, making a living out of his music was his main objective as a sacrilege to this monument of musical history. On the contrary: it should induce to even more respect. We need to see this man as somebody who had taken a decision with an uncertain outcome, and this takes courage. The living conditions of the working class in which arose the blues were hard, but wasn’t it even harder to take a gamble on the possibility of earning enough money by making music? Some of them combined the job of entertainer with other working activities, but others had definitely chosen to go out on the street, join a touring group, or go out on tour all alone, leaving everything else behind.

As I already stated above, this man had learned the job the hard way by carving out his technical skills out of life itself and by learning from what he heard from relatives, neighbours or touring musicians. Do not let us fall into the pitfall of considering this learning curve as simple, or of seeing this as an easier way of learning compared to drawing from formally qualified teaching sources. I would say that it is just the other way around. It required hard work and lots, lots of practice to fine tune techniques just by hearing others play. He had to design his own learning curve and didn’t have the luxury of stepping into formalized teaching structures.

The hard practice in self study was even an absolute necessity if the choice had been made to make a living out of music, whether it was as a full time or a part time occupation. Just as any business man will confirm in whatever sector, success is a matter of responding adequately and with insight to the market’s desires. In an independent occupation, the only person upon whom one can rely is yourself. Perseverance is a condition for a positive outcome.

The early blues man had taken also a step out of the dominant economic structure. In the Southern states this economy was largely determined by, on the one hand, the sharecropping and tenancy system, and on the other hand the start of the industrialization: coal mining, cotton industry, logger companies … In any case, the working and living conditions were harsh, and it is quite understandable that some had turned their eyes at another way of living even if this alternative livelihood didn’t offer better guarantees, quite on the contrary. Pursuing a musical career was not a social promotion, but a change of life track which did not necessarily lead to a station with more material opportunities. There was by the way also another, non-economic implication: though the early blues artist may have been subject of admiration by his contemporaries for the courage of having thrown off the chains of sharecropping and tenancy, and thus escaping a merciless system, at the same time he put himself partially out of the system of ruling social norms. Blues was considered as the devil’s music and by playing it the performer challenged the reigning religious system. Talking about this struggle between the secular and sacral brings always to my mind the personal pain that Howlin’ Wolf must have felt when, after having made it in Chicago, he met his mother again after a long absence: when the son offered his mother financial assistance she threw the dollars back to him on the street, shouting that she didn’t want any money earned by playing the devil’s music.

The ‘freedom’ from having to function in the dominant economic structures often came with a high social and personal price.

In any case, finding the audience and appealing to this audience was a condition sine qua non for the possibility of pursuing this chase for freedom. This implied that one needed to be able to give the audience what it wanted; and this audience liked popular music, which was not limited to blues. The repertoire of the early blues artist as a result needed to contain more than just blues songs, but also popular ballads, Tin Pan Alley songs. Coon songs were not excluded. The popularity of the blues didn’t come overnight by the way: blues was in its early days associated with a new generation, and there was a process of adaptation that preceded its infiltration on the repertoires of the artists performing in juke joints, at picnics or frolics.

It was (and is), as also already underlined above, characteristic of the (early) blues performer that in the live act the performer and the audience melt together, the ‘I’ of the performer fuses with the ‘WE’ of the audience to become one.

This does not necessarily mean that the performer identifies himself totally with his music. What is important is that the audience gets what it expects to get, even if this implies playing other genres than the blues and putting aside personal preferences. This capacity can be considered by the way as a characteristic of a true professional entertainer.

One can argue from the above that the early blues man enjoyed a high degree of autonomy, in other words, that he had the capacity of determining himself the direction in which the train of his career took him, only limited by the preferences set out by the wishes of the public he wanted to reach. There were no intermediary bodies that arranged for him where he would show up the next day; there was nobody else to manage his agenda on where and when to perform, other than himself. This of course meant that managerial skills were a definite asset. Not only did he have to possess a detailed geographical knowledge of where to go (and this was often hundreds of miles far), he also needed to have the sense of feeling what audience to choose and what the audience liked (or accepted!). His autonomy and (relative) freedom was thus only possible because he combined true artistic with managerial talent.

I don’t hesitate thus to view the early blues artist not as a romantic, wandering individual that sacrificed his life for the sake of music, but foremost as a highly talented self-taught and versatile artist, trained by the hard life, disposing of a high degree of autonomy and who knew precisely how to integrate with his audiences, even if this implied playing other than blues songs. He was a talented business entrepreneur who had a thorough knowledge of this market, knowledge which was indispensable for making money. Only by selling himself, he was able to survive.

You will have noticed that so far I made no allusion in my definition to the racial aspect, the skin colour of this performer. I did not want to mention this aspect as a separate dimension since I believe that it risks to create an artificial split between what has become defined in the last decades as “black” and “white” music. This split is in itself historically a very interesting topic for study but putting it on a pedestal as an independent criterion is doing it too much honour. The segregation of sounds, as Miller calls it, is an historical event/process that is as such an extremely interesting subject, but it would be wrong, I feel, to study the emergence of the blues from this perspective. It would be as looking at the past through a prism that has been created by previous generations. What we need to do is try to look at the past with criteria that are as much independent as possible from the very historical evolution which we try to make the focus of our study. This is why, I try to define the approach of the blues from an angle which in the first place involves the artist himself and try to look at the historical and social context starting from there out.

You will have noticed that so far I made no allusion in my definition to the racial aspect, the skin colour of this performer. I did not want to mention this aspect as a separate dimension since I believe that it risks to create an artificial split between what has become defined in the last decades as “black” and “white” music. This split is in itself historically a very interesting topic for study but putting it on a pedestal as an independent criterion is doing it too much honour. The segregation of sounds, as Miller calls it, is an historical event/process that is as such an extremely interesting subject, but it would be wrong, I feel, to study the emergence of the blues from this perspective. It would be as looking at the past through a prism that has been created by previous generations. What we need to do is try to look at the past with criteria that are as much independent as possible from the very historical evolution which we try to make the focus of our study. This is why, I try to define the approach of the blues from an angle which in the first place involves the artist himself and try to look at the historical and social context starting from there out.

Already in my previous articles, I have made it clear that the early blues crossed the colour line. The categorization of music into white hillbilly on the one hand and black blues on the other hand is largely the result of the emergence of the technology that imposed itself into the music business since the introduction of the recorded sound and the radio technology. Historically, we see that the ownership of the intermediary bodies between performer and audience, and thus the loss of autonomy of the former, went hand in hand with the impact of the social hierarchy in the music business. Record companies put black artists into ‘race records’, which in itself was not a demeaning term, but had to made it clear that it was a separate niche market clearly to be distinguished from the ‘white’ market. The fact that this technology was on top of that in the hands of groups located in the Northern States, which had developed – for all kind of reasons – strong stereotypes of the Southern “black coon” and the “white rube or hayseed” living in the Appalachian is not neutral. The duality North-South has found in my opinion also a clear articulation in the definition of ‘black’ blues and ‘white’ hillbillies which were seen as links to the ‘authentic’ historical background of the United States.

With all due respect to the early folklore research and to the work of scholars as for instance father and son Lomax, we need to remain critical and examine whether this research was also not biased by a prejudged distinction between black and white music. Did this research not start from the false premise that by definition an artist singing the blues was to be a black artist? Was the research not filtered by erroneous expectations, leading to a narrowed attention for the repertoire of the early blues musicians where there was seen only room for the blues genre in a repertoire that was much vaster than only the blues? I am convinced that both technology and to a high degree also the early academic interest in what was called folk-music lead to a choked view on the versatility of the musicians. Injustice was done to their artistic and entertainment capacities (see also Miller, 2010).

There were important crossovers between the races on the musical level before their sound became artificially segregated.

* White artists also had the blues on their repertoire:

There were numerous white artists who drew heavily from the blues repertoire. Either they incorporated it into their own repertoire, or they covered blues and hokum songs. An excellent overview of such material has been collected on the double CD-set “White Country Blues 1926-1938″, issued in 1993 and that comprises such star artists as Roy Acuff and Frank Hutchinson, but also numerous other less known names. The overview is however far from complete. There have been many other different examples as I presented in a previous article (http://www.myblues.eu/blog/?p=986). A particular striking case of cross-pollination is the one of Jimmie Rodgers who is considered to be the first hillbilly, country star. He became known as a.o. the “Blue Yodeler” and the “Father of the Country Music”. It stands however that Rodgers’ Blue Yodel songs were based on the 12-bar blues format and that he got a great deal of his inspiration from the blues folk music. Some don’t hesitate even to call him in the first place a blues man.

In another recent article, I have highlighted the work of Moran Lee ‘Dock’ Boggs, who has found his inspiration in the playing of a black guitarist ‘Go Lighting’ and who is said to have had the idea of playing the banjo like a blues guitarist from the black banjo player Jim White (http://www.myblues.eu/blog/?p=1237).

There is thus ample documentation of white artists who have learnt their job from black fellow musicians and who have included the ‘black’ blues in their repertoire.

* White audiences also requested for blues songs

Though much further research needs to be done here, there are enough indications that substantiate the statement that the white audience also sought out the blues, not only on stage, but also on record. This is understandable if one considers the social situation of the working class part of the white population, a situation which (abstraction made from the racial aspect) was not that far away from this of their African American contemporaries. “Some white-working-class listeners found that the blues spoke to their own sense of marginalization and loss” (p. 81).

Social-psychology could also give us some insights in this matter: by listening to the blues, the white listener could peep over the colour line, whilst he remained safely on his side. Perhaps he also found in the strong sexual undertone of many a blues song an outlet which he was not able to get from the white popular tunes.

* Black artists had mixed audiences and some even played (initially) mainly for white audiences.

This aspect of the crossover of the colour line is much more documented. Playing for a white audience had clearly its advantages over playing for a black public. For a start, performing at white houses brought more money in the pocket. Big Bill Broonzy earned his first manufactured violin from what he earned playing for a white public. Sam Chatman has also explained in interviews that playing at white parties generated a substantial higher profit than playing for black parties. Usually, the former also brought along more fringe benefits in the form of food and drink. On the non-material level, performing for a white audience also meant that parties didn’t last as long as for the black ones, which implied extra hours of sleep (very welcome especially if the next day another job was waiting). Some have also admitted that white parties offered a less violent context. The lower level of aggression during white shows was probably in the first place linked to the fact that they were less the subject of the attention by formal (or informal) law enforcing bodies than black parties, which were quite often in the visor of police harassing.

Jim Crow may then perhaps have been less markedly present on the musical scene, once on the street, the African American musician became however again as any other African American. His social role as musician protected him more or less against the merciless aggression from the segregation, once he put his fiddle, guitar or banjo aside to go back home or to whatever place he stayed overnight on a tour, the normal play was again the order of the day.

* Black artists also had ballads and other popular songs on their repertoire that are usually associated with ‘white’ music

The higher the musical versatility the better the chances were of getting paid for the job. Chatman declared in an interview: “You take a fellow that can play anything, he can get a job more or less anywhere.” The more diverse the repertoire, the broader was the audience to which the early blues performer could appeal.

The eclectic approach that was clearly present in the repertoire of the medicine shows, the breeding ground of many early blues musician, was also present in the work of later stars of the blues. Considered by many as the “father of the delta blues”, Charley Patton for instance is also described by Robert Palmer as a “jack-of all-trades bluesman” who played “deep blues, white hillbilly songs, nineteenth-century ballads, and other varieties of black and white country dance music with equal facility”. Quoting Elijah Wald, we can also mention Robert Johnson who “in his own time was most respected for his ability to play in such a wide variety of styles—from raw country slide guitar to jazz and pop licks—and to pick up guitar parts almost instantly upon hearing a song”.

Into his most extreme expression, black artists would paint their face black in order to gain entry on the musical stage. Obrecht (2011) has vividly described what this meant for vaudeville artists as Williams and Walkers. Gus Cannon also grabbed at the cork to paint his face black when he started touring with medicine shows in 1914, not that he really liked it: he later told that he had to have a good shot of liquor before going on stage after having put cork on his face and having his mouth painted white (Miller, p. 70).

++++++++++++

In our present day conceptions we have some difficulty in presenting the early blues performer as a professional. Yet, this is what he essentially was: a highly skilled professional entertainer, who needed to know what the public wanted. To reach as broad a public as possible he needed to juggle with styles taking into account also the ethnic composition of his audience. As Miller articulates it: “Two of the most significant aspects of their self fashioned careers were the abilities to play fast and lose with musical styles and show a conscious disregard for the color line that was coming to characterize the Jim Crow South” (p. 54).

Playing music was for him an alternative mode of employment, offering an escape from the existing, oppressive economic conditions. It allowed him to stop working, or at the least to engage in a job that he self controlled, through skills he had taught himself by hard practice.

Music was the gateway out of harsh labour conditions for both the black and the white artist.

It is no disgrace to his musical talent to highlight that money was an important issue, a primary concern. My respect is no less for Blind Lemon Jefferson for instance when I read that he was able to hear by the way a coin fell how much he was paid and that he insisted that he “wasn’t played cheap”.

No words can better summarize it all, than those of Roosevelt Sykes (Miller, p. 75):

“Blues is like a doctor. () Doctor studies medicine; course he ain’t sick, but he studies to help people. A blues player ain’t got no blues, but he plays for worried people. He don’t really have no blues when he play em but he has the talent to give to the worried people. See they enjoy it. Like the doctor works from the outside of the body to the inside of the body. But the blues works…on the insides of the inside, see”.

Blues is what he does.

____________________________________________

Sources

____________________________________________

– Karl Hagstrom Miller, Segregating Sounds, 2010

(which I give credit for a number of quotes in the text)

– William Howland Kenney, Recorded Music in American Life: The Phonograph and Popular Memory, 1890-1945, 2003

– http://www.allmusic.com/album/white-country-blues-1926-1938-a-lighter-shad-of-blue-r175322

– http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tin_Pan_Alley

– http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coon_song

– http://jasobrecht.com/bert-williams-george-walker-early-years/

[comment mailed to the author by Ohenio Prince, member of the Ebony Hillbillies, after posting a link to the article below on the Facebookpage of the Ebony Hillbillies]

There is a great public library system in NYC if you cannot afford to buy books in bookstores or on Amazon that provide basic information about Blues, Black and general musical history, and related topics.

this article of yours, is interesting only to people unfamiliar with the real history of the blues and of African american and american music and who have never read anything contemporary or serious about this. This is pretty much drivel.

This is pretty ignorant worthless crap, an example of the racism that allows a white person to become an expert on black people’s culture without bothering to know or investigate anything serious about it, including the good work other white people have done about it.

This is more an example of typing than writing.

I read about half of this and then decided that it would be better for me to stare at the wall and drool than continue reading.

“It is a well known fact that (early) blues artists and their ascendants developed their musical techniques in the ‘school of life’.

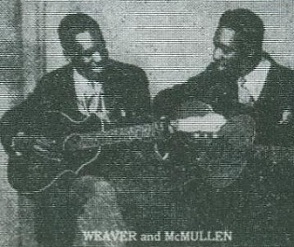

This is not a well-known fact. Most blues musicians that I am familiar with developed their musical techniques in their family or from immediate friends of their family (typically a boyfriend of a mother) or developed themselves through whatever process of formal musical training were available at the time. A significant number of blues singers like Sam Chatmon whom you briefly mention were products of musical families where making music was the family profession and in which they were expected to start making music from an early age in often graduated sets of musical roles. Chatmon talks in interviews done with him about the schooling in music =(Chatmon could read music) on several instruments required in his family. Chatmon’s family is the Mississippi Sheiks that included him a brother and a cousin and on and off a couple other relatives. Charlie Patton is often alledged to be part of that family, but he was not, Patton’s mother had an outside child other than Charlie with Chatmon’s father. Chatmon’s father is estimated tohave had 40 outside children!

It seems from your writing,that the Blues is a stereotypical black rural illiterate person from Mississippi who plays a guitar. However, it is fairly clearly that when people interviewed such blues musicians considered the apex of the blues to be blues musicians like Lonnie Johnson—the most recorded blues musician in history with more than 300 recordings who made charting records from the 1920s until the late 1940s—Bessie Smith, and Ma Rainey and that their audiences considered these musicians to be the best of the blues.

Blues stars emerged in Black show business singing songs that were blues by around 1910-1915 and published songs even by white composers and show business. Even European American popular music as expressed in national sheet music hits had significant components of songs with blues-based musical structures as top-ten hits by 1910.

You speak of “the second half of the century.” Blues did not develop as a distinct genre until the 20th century. If you are trying to talk about the whole of Black music in the 19th century then, this is a dumb folkie stereotype of things, skipping all of the formal black musical development in African American, European American, and European music that was central to the development of Black music throughout the 19th century.

In particular you show an extreme ignorance of the music genre that preceded the Blues. Blues music seen initially as just another variant of, ragtime, which was both an art music, a popular music, and a folk music. The story of 19th century African American music is a story of African American conquest of all sorts of formal European and European American origined musical techniques, instruments, and forms, and their refashioning for African American use or as products for white people.

These are some of the points you have missed, and they are telling. Please refrain from posting your unfortunately inaccurate blog on our Facebook page.

Thank you,

O.H.Prince,

The Ebony Hillbillies

Comment submitted from Ohenio Prince, on Facebook Group from the Ebony Hillbillies, as a reaction on the above article :

The information posted on this site by Mr. Bosman has no endorsement by the Ebony Hillbillies, and is also utterly without merit and at times just plain stupid. A cursory glance betrays the fact that Mr. Bosman knows no more about the history of the blues or Black music than a slab of Granite!

date : 15.08.2011

[…] Continue Article Here… http://www.myblues.eu/blog/?p=1329 […]