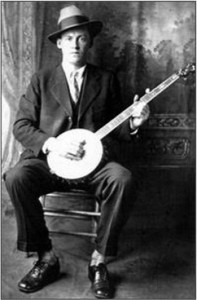

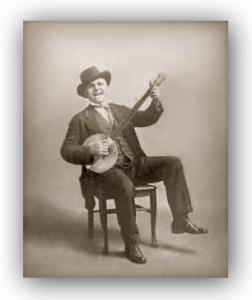

One of the earliest recordings of Uncle Dave Macon in 1924 during his session in New York was ‘Hill Billie Blues’. It was the first song, according to Charles Wolfe – a country music historian – that carried the word ‘hillbilly’ in its title. Uncle Dave Macon (1870–1952) was an American banjo player, singer, songwriter, and comedian. He gained regional fame as a vaudeville performer in the early 1920s and would later be a star of the Grand Ole Opry. As Charles Wolfe wrote, “If people call yodelling Jimmie Rodgers ‘the father of country music,’ then Uncle Dave must certainly be ‘the grandfather of country music’.

In our present terminology we tend to associate ‘hill billie’ or ‘hillbilly’ with white country music, and ‘blues’ with black, African American, folk music. We like to see it as two genres that exist on different sides of the segregation fence, two different musical spaces entertaining an audience on different sides of the rope dividing the dance floor into a white and a black group. This approach however seriously distorts our view and stands in the way of the full understanding (and appreciation) of the roots of American (and present pop) music. Uncle Dave Macon for instance, the grandfather of the country music, had a significant repertoire that he had learned from black singers, and his ‘Hill Billie Blues’ was a reworking of W.C. Handy’s ‘Hesitation Blues’ (Wolfe). Clearly, on the field, the racial dividing lines that record companies tried to maintain were not as impenetrable as they seemed at first sight.

Isn’t it for instance striking that Jimmie Rodgers, the father of the “country music”, boosted his recording career with a little help from the blues? Ralph Peer, at that time talent scout – but above all a shrewd business man – for the Victor Talking Machine Company, recalls that Rodgers didn’t really have enough material to record when he had gone over to New York for a follow up on his Bristol session, and that at the end of the day he agreed that Rodgers performed one of his blues songs. It was initially called ‘T for Texas’, but was finally released as ‘Blue Yodel’, the start of a success story in the American country music. Lesley Riddle (1905 – 1980), an African-American (blues) musician, had a decisive influence on the shaping of country music by the Carter Family. Some go even as far as to say that country music may well owe its very existence in part to this one-legged African-American (Steve Leggett, Allmusic).(1)

Another illustration of the ‘vagueness’ of the racial division line was visually very notable during the field sessions which were organised by the record companies. “Black songsters sat waiting next to white gospel quartets; black blues singers took their turns with white fiddle bands. The give and take between white and black music “in the field” was always greater than the segregated record companies implied.” (Wolfe). And, try it out yourself: close your eyes when you listen to some of the early folk recordings of the twentieth century and make a bet on the colour of the performer. There is a fifty to fifty chance for a great deal of them that you can’t link a skin colour to the voice. Well, neither could the listener then at the time. For some performers, even today, not enough material is available to make a definitive statement on their racial background (see a previous post here on the “Two Boor Boys”). The case is also documented of the (white) Allen brothers, looking like a couple of “well-mannered college students”, who were fascinated by the blues songs that they heard around them and who initiated a lawsuit against Columbia because in its rush (and perhaps clumsiness (see my post here)) the record company bosses had published their recordings in the “race record” series in 1927, which was clearly not what the Allen brothers had expected. Finally, they dropped their lawsuit, signed with the competing Victoria and made a career with … blues songs. Blues was popular and rewarding.

Even if we admit that the label blues was often misused by some musicians and was added to many songs which were not (formally) blues only because its label was valuable on the market, the above makes clear that – I try to find the correct words – it would be a mistake to interpret the roots of American folk music, country, rag, jazz, blues and other, along the sole dimension of race. It is tempting at this stage to raise questions such as: is blues only black, or: can whites play the blues? I have the impression that this discussion is still heavily emotional and that even raising this type of questions is still today sometimes avoided. It seems at least extremely hard to approach the issue in an unbiased way, as I concluded from a reading from Paul Garon’s article called ‘White blues’.

I dare to assert that raising such questions stands in the way of a complete understanding of the historical evolution of blues and its roots. I tend to agree with the hypothesis that a combination of two dimensions is essential for a full understanding of the blues genesis:

(a) the social and ethnic mixture, and

(b) the social and economic change after the Civil War.

Both need to be viewed together. Trying to apprehend blues only from a one dimensional, racial/ethnic, viewpoint, would be as trying to understand the human being only from the outside. It is as scratching on the surface, without going deeper into the matter.

Social and economic change is the basis for the emergence of new musical styles and forms. In a stable social environment, I believe, music can mature and reach higher levels of complexity by the genius of individuals, but it will finally end up in a dead end street. Music can be the carrier of traditions and convey stories and tales from one generation to another. It is functional for the balance that a society can reach. Music can thus have a conservative function. By the absence of social change, the horizon of a particular reigning musical style is however limited. Musical styles need the impetus from dynamic social and economic forces to change, to further their growth to new tunes and lyrics. A new sonic vocabulary can for instance grow as part of a subculture in a subpopulation that contests the ruling norms and wants to defy the social equilibrium.

In the same way, the Reconstruction and Post-Reconstruction period in the Southern states testified of an American society that tried to find a new equilibrium after the overturn of the slavery system through the Civil War. The times were not only hard, for all social layers, the changes that presented itself were far reaching.

For the “freedmen” the challenge was no less or no more than the construction of a total new society, since the white population made it very clear that there was no place for the African Americans in their social space. Separate but equal. The cultural background of the African Americans was largely devastated by more than two centuries of slavery, and their task was it to invent a whole new system of social and cultural norms that made it possible to survive next to a white population that at the same time needed to tolerate the African Americans, but could not exist without them. This was the dualism. The situation was more to comprehend in terms of ‘separate and interdependent’ than ‘separate and equal’.

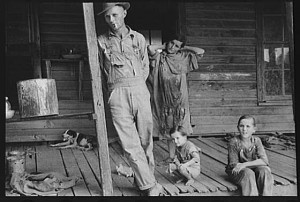

The African Americans were freed from their shackles but were soon chained again by the inexorable system of debts in the sharecropping and tenant relation. The situation was however not fundamentally different for the white agrarians in the cotton and other sectors who did not own any land, or only a small piece of it. Survival was for them as much a daily challenge as it was for the African American ‘freedmen’.

What’s more, the industrialisation entailing a profound change from an agrarian, rural society to a mechanized, urban society had a far reaching impact on the daily lives of all, irrespective of their skin colour. Some regions which had been populated for centuries with self subsistent farmers were often in no more than a decade or a generation transformed into an industrialized environment. It often implied that in a span of a few years people had to abandon their farms and had to look for low wage jobs in most often hazardous industries. They lost in this process also a major part of their independence, as they started to work for anonymous companies. It is simply beyond our imagination to try to grasp the impact of those changes on families and individuals.

All this made it necessary that new forms of cultural expression needed to be sought that translated the new social experience. The sounds and lyrics of the past proved to be no longer functional in a social fabric which was fundamentally altered. I believe it to be crucial for the understanding of the blues that they were a means by which the most impoverished of society sought a way to regain self-respect. The constant humiliation and dehumanization from which the most exploited part of the population was the victim needed desperately an antidote and blues was an instrument that allowed it to recapture this dimension of their being that was perpetually threatened by the capital owners that expropriated their labour. The preservation of self-respect: it was, next to the scarce means of livelihood, the only thing that kept them coping from one day to another. Music was an entrance into a world with different standards of regard and respect (Barry O’Connell).

This was not different for the black and for the white bottom layers, the poor working class, of society. Through music it was possible to maintain what is fundamental for survival in inhumane conditions: self-respect. This reminds me of the importance that music had in the German concentration camps in World War II: ” Music gave the prisoners consolation, support and confidence; () it helped them to articulate their feelings and to deal with the existential threat of their situation emotionally and intellectually.” (Guido Fackler)

The radical social changes that unfolded in the Southern states during the second half of the twentieth century provided only the structural context of the birth of new musical forms. It was the formal framework, the “conditio sine quo non”, but does not fill in the framework. The content of the musical change was of course dictated by the existing traditions and sounds upon which the new sonic forms found a fertile soil to blossom. The central element here is the social mixture, the ethnic melting pot that is the basic characteristic of the American social and cultural structure. In very simple terms one could evoke the image of a stew that is braising, and that social change is like the spoon that is stirring in the stew. A good stew can only be made up of ingredients which go together, which are compatible. They need to have the intrinsic characteristics to be able to blend together into a new, other taste that can only exist by its very mingling. The whole is much more than its constituent parts.This is the way that I see the emergence of the blues and of its subsequent forms in boogie woogie, and related styles as ragtime and jazz. The second half of the twentieth century in the Southern states presented a historic unique combination whereby deep social changes caused a further specific mingling of some, mutual compatible, ethnic cultural forms leading to new musical forms of expression. The latter were neither European, nor African, they were truly American. Given different social environments, rhythms of changes and different demographic relations, the stew could of course differ from one region to another. Also, it is evident that some isolated, mountain regions, which were only in a later stage connected to the broader society by the new means of transportation (train in the first place), showed different developments than regions with earlier processes of industrialisation. However, the changes were inevitable, influenced as they became also by the ruling force of the standards set by the new technologies of radio and phonograph companies.

I think it is important to underline, before going further, the notion of compatibility that was an essential condition for obtaining the final mix that resulted. It is worthwhile investigating to which degree the language itself was a condition for the pollination of the different ethnic components. The language barrier was in my opinion crucial and set a determining element for the ethnic mixture. The ruling white class of early colonists and the African Americans, who were imported as slaves had after all lived together for some two centuries and despite their social distance, they ‘understood’ each other, spoke basically and formally the same language. There had been a giving and taking of certain cultural elements, even if black and white were not always conscious of it. Some authors (George Pullen Jackson) conclude that most so called Negro melodies were in fact variants of old European tunes.

To summarize : there has grown in the second half of the 19th century a large, common pool of tunes and lyrics of which it was very difficult to say whether their origin was black or white. If their African and European ancestors would have been able to hear them, they would not have recognized their heirs in the African and white folk musicians of the 19th century (William Hogeland). This common pool is in flagrant conflict with the efforts deployed in the 20th century to categorize music into genres which can be neatly arranged in the record crates of the stores.

Crucial for the emergence of this pool of music was not slavery as such, but rather the abolishment of slavery and the radical social changes that occurred in its aftermath, in a multi-ethnic environment in which the social changes also lead to important streams of migration. The social and economic changes in a multi-ethnic space required a new cultural codification, a new tonal vocabulary for the new times and altered places. The approach to the understanding of the musical changes in the 19th century thus needs to be a dynamic one which takes into account not only race, but the change of the complete socio-economic fabric. The ‘itinerant’ musician is more than an accidental symbol, it is the expression itself of the change, of the social disruption, of the attempt to escape from the existing structures and of the effort to give shape to a new world. The old world was no more, and the new one was still many miles away, only a vague hope.

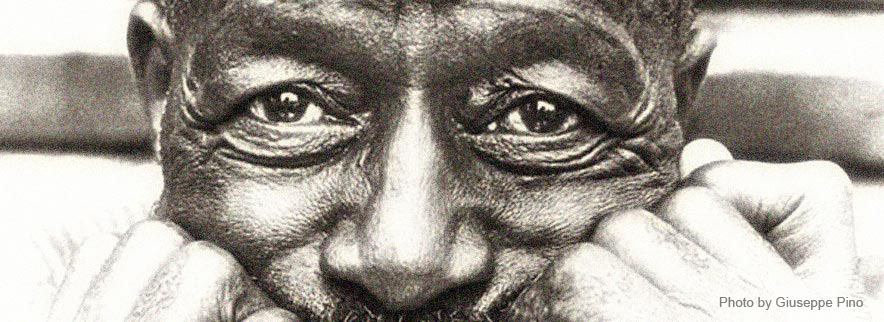

The biography of many early folk artists is apt to illustrate the above assertions, but I believe that there is one who merits some further attention also because he is largely unknown in other than blues and country music aficionados’ circles: the career of Moran Lee ‘Dock’ Boggs. He showcases a perfect illustration that blues is not only ‘black’ and that blues can be played on other instruments than guitar or piano. His very particular style was a mixture of black, white tradition, blues, ballads, gospel and he admired a lot the early female blues vocalists. He offers a synthesis of blues and old mountain styles. Boggs’ musical career can be perfectly depicted against the background of a social texture which fundamentally changed in no more than a decade from a self sufficient agrarian society into an industrialised environment. In parallel, we see in his biography the evolution from music as an intrinsic part of the daily life, in which performer and audience are ‘one’, to a market driven music with a growing distance between the performer and his audience, a distance that is filled up with talent scouts, record producers and companies and profit maximizing dogmas.

On the side line it is ironic to notice that his coming and going on the musical stage was partially inspired by the sacral-secular conflict that was so typical of the early generation of blues performers: his wife regarded his music as the devil’s music and was more an obstacle to his career than a promoting factor. Finally, Boggs had a second career in the sixties during the folk revival, as had many other blues artists from his generation.

Boggs was born in 1898 in Norton, Virginia, in a period which witnessed a profound mutation from an agrarian society to an industrialized region as a result of the introduction of the rail road and the development of the coal mining sector. The farmers had, as it were, from one day to another, to give up their agrarian activities and go out to look for jobs paid at starvation wages in a hazardous coal mining sector. Very often, this meant also giving up their houses and moving to another place.

This development was accompanied with an important immigration of African Americans in this traditional, isolated, region of white mountaineers. Even if blacks were often given the most dangerous jobs, blacks ‘were moving into the area to work alongside white mountaineers, who were seeing their old ways of farming and logging give way to the newer world of unions, mining bosses, and company stores” (Charles Wolfe). The sharing of working conditions went hand in hand with sharing music. There was a large amount of interaction between black and whites, also on the musical level. Both black and white were confronted with the same need to sustain themselves in a perpetual disrupted economic and social world. Coal operators played here the role of the plantation holders.

Moran Lee ‘Dock’ Boggs was the youngest of ten children and started working in the coal mines at the age of twelve, in ten hour shifts. It was also around 1910 that ‘Dock’ started to be interested in playing the banjo – it is said that he traded his watch for a gun, then trading the gun for the banjo. The banjo was then rather recently introduced into the mountain music, probably through the minstrel shows and black musicians that accompanied the railroad works.

The next ten years would be his musical formative years, with influences from different sides. Though his siblings were also into music, he made it clear from the start that he didn’t want to play like his brothers and sisters. He would like to learn to ‘pick the banjo with his fingers’. He admired the playing of a black guitarist who went by the name of ‘Go Lighting’ and who often played the ballad ‘John Henry’ at Dock’s request. It is told that he got the idea of playing the banjo like a blues guitarist from the blue-eyed black banjo player Jim White (what’s in a name?) who visited his house. Boggs’ essential contribution to music lies indeed in the adaptation of the techniques of black blues guitarists to the banjo – “a step most other white players never dreamed of taking” (answer.com). He once said: “You think them blues ain’t here on this banjo neck, the same as they’re on that guitar? They’re just as much on this banjo neck as they are on that guitar or piano, or anywhere else if you know where to go and get it and if you learn it and know how to play it”.

Boggs may not have been the greatest instrumentalist; it is foremost in his unique accompaniment by the banjo to his vocals – an intense, moaning style of singing – that he should be considered as a seminal figure. He disposed of a very personal sound unlike that of many others: a combination of African and Anglo-American instrumental styles. His songs are often dark and unnerving, some are sunnier.

Music was not the source of living for Boggs. He kept on working in the mines. His music remained imbedded in the community in which he lived; it was an integral part of community life, i.e. just another aspect of the communal setting. And this communal setting, characterised by a particularly intense and fast social change, proved musically very fertile. It was characterised by the ‘interactions of an astounding variety of cultural groups: African Americans from all over the South, Hungarians, Italians, Greeks, Poles, and Ukrainians, to name only a few. Each embodied different musical traditions. Added to the mixture was the presence of people from other, formerly isolated, parts of the Southern mountains who brought rich local stylistic traditions, different song, and alternatives to familiar ones.” (Barry O’Connell). And as O’Connell describes it further very well: “In the mountains the presence of so many culture groups and sub-groups created a rich and exhilarating musical world. The explosive combinations of styles, instruments, and new songs that resulted constituted an expressive feast, and one of the great periods of creativity in American musical history arose from it. New social constructions and the coming of a fully industrialized capitalist economy also meant that every mode of expression was being tested and pressed by experience requiring new form and eliciting powerful feeling”.

Boggs’ view on the place of making music in his life changed when in 1927 he was persuaded by a friend to go to a hotel in Norton where two representatives of Brunswick records in New York had an audition for more than 50 candidates. Dock was – to his great astonishment – one of the few selected, and was subsequently invited to travel to New York to record. These recordings are considered by O’Connell as an important chapter in the documentation by commercial record companies of the history of Anglo, African, and ethnic American musical traditions.

However, his (pre war) recording career was very short. He only recorded some sides for Brunswick and some for an obscure company “The Lonesome Ace”, which had a very short life span.

Locally, Dock’s record met with quite some success, which inspired him to form a band and play for parties and dances. From the fact that he hired a young lawyer to act as his manager, one can infer that Dock saw his musical career in a larger time perspective and that giving up coal mining was no idle thought for him.

However, things didn’t exactly go as he expected. Different factors can explain why after some time he had to give up the idea of never having to work again in the coal mines. The economic depression is one of them, but there is also the firm indication that his wife pushed him to stop playing that ‘devilish music’ (the love for his wife must have been great since he became even a deacon of his church in 1942). When offered a spot on the radio, he also had a sudden attack of microphone fright and was barely able to perform. This may sound strange for us now, but let us not forget that at that time it must have meant a huge leap to go from performing in a communal setting to a technical studio environment with horns, microphones and red lamps which told you when to start and stop playing, and above all: without an audience that had always been an essential part of the energy of the performance.

In 1963 Dock was living a quite, anonymous life in Virginia when Mike Seeger, folk musician and folklorist, discovered him and brought him again in the spot lights. He recorded again and was performing live at the American Folk Festival in Asheville. He was for the first time making a living out of his music, enabling him even to buy his first new car. However, he did not enjoy his newly acquired status very long. He died at the age of 73 from health problems.

I started this article with Uncle Dave Macon who recorded ‘Hill Billie Blues’ in 1924. I hope that after reading the above, this title and song do not longer seem to you as a contradiction in the terms, but rather as the pure and irrefutable expression of a tremendously rich musical space that emerged in the Southern American States in the late 19th and early 20th century. If you do, then I consider my mission as accomplished.

___________________________________

(1) The examples of the impact of African American blues artists on white ‘country’ can be multiplied (Arnold Shultz, Rufus Payne,…), just as the other way around, many African Americans let their style and sonic production guide by what they heard from white performers. For the moment, I would like to suffice with the reference to a number of links which have been provided to me by the kind cooperation of Michael Hawkeye Herman. I would like to dig further into this matter in a later article.

– http://www.tvgnc.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=4&Itemid=2

– http://www.tvgnc.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=5:leslie-riddle-bio&catid=6&Itemid=3

– http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arnold_Shultz

– http://www.cmt.com/news/country-music/1486323/hank-williams-the-biography-book-excerpt.jhtml

Sources :

_________

– Charles Wolfe, A lighter Shade of Blue – White Country Blues, 1993

– Charles Wolfe, Development of Country Music

– http://www.music.ucsb.edu/projects/musicandpolitics/archive/2007-1/fackler.html

– http://myforum.mississippijohnhurtnews.com/user/discussion.aspx?id=168859

– http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Coal,+Class+and+Color%3A+Blacks+in+Southern+West+Virginia,+1915-32.-a014903077

– http://www.wvculture.org/arts/ethnic/african.html

– http://books.google.com/books/about/Coal_class_and_color.html?id=nF-963i4uiUC

– http://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/25

– http://www.answers.com/topic/dock-boggs

– http://zeppmusic.com/banjo/dboggs.htm

– http://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/issues/98nov/banjo.htm

– A journey of the blues, Up the Mississippi, Eunice Boardman, Ed., 2002

– Paul Garon, White Blues (From Bluesworld online)

– Barry O’Connell : Dock Boggs : His Folkway Recordings, 1963-1968, 1998

[…] Continue Article Here… http://www.myblues.eu/blog/?p=1237 […]