In his biography on Deford Bailey, D.C. Morton quotes the former: “”A white barber asked me one time how I could mix them (eb : white and black customers) up in my shoeshine shop and using the same seat. He said they’d run him out of town if he did that. Well I said, ‘They all know me and all want to hear the same tune.‘”

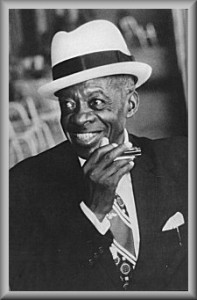

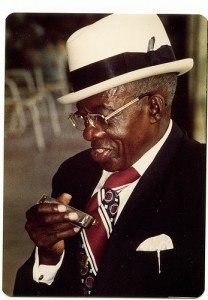

Deford Bailey spoke as the owner of a shoe-shine shop in the South which did good business because the customers, black and white, came in not only to have their shoes polished, but also to hear the shop owner play his harmonica. Once, Deford Bailey was a radio star…he was the “Harmonica Wizard”, loved by both black and white throughout the South.

If there is one artist who challenges every attempt to draw lines between black and white music, who derides all tentative to segregate sounds along racial or stylistic concepts, then it is him.

I will be honest. I never heard of him until this week (or at least did not pay any attention to him), when I was reading an article on the history of the harmonica in the blues. I read that Sonny Terry was a big admirer of him, that Sonny Boy Williamson (II) had heard him on the radio (1) and that he had inspired many more in the later evolution of the harmonica music. But wait a minute: in 2005, this man was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame at Madison Square Gardens in New York City. He was black, was he not? Moreover, he was on the radio, while blacks were generally excluded from this medium in the twenties. I went out on the Internet to look for his music. On one site (allmusic.com) his style is labelled as ‘blues’ and ‘pre-war country’, another one sells a compilation album in the series ‘The Best of Blues’, but in the genre ‘Jazz’. Most of his recorded songs contain the word ‘blues’. He began to puzzle me even more as I learned that he has been the greatest star on the ‘Grand Ole Opry’, the longest running country music radio program that had started off in 1925 under the name of “The Barn Dance”. Deford Bailey had furthermore not only been the one who – according to many sources – had inspired the change of name of this radio program to the ‘Grand Ole Opry’, he has been the first artist on the air under the new flag and has been the most popular one with the largest number of live broadcasts between 1926 and 1941. On top: his seminal song ‘John Henry’ had been issued separately in RCA’s “race” and “hillbilly” series. He was also one of the first artists whom Victor had recorded in Nashville (1928).

I was left perplexed, and my night was short: I could not stop enquiring further before turning to bed. And to my great astonishment: plenty of material was available, including a biography (2) containing first-hand information from the man himself, including audio-material from interviews with him.

Giving the excellent material easily available I won’t go into much detail on his life course (3). He was born in 1899 some forty miles below Nashville and was raised by his father’s younger sister when his mother died (oh irony: his father’s name was John Henry Bailey). At the age of 3 he contracted polio and was confined to bed for a year, only able to move his head and his arms. This is the time when he started to play the harmonica. As he said : “My condition made me develop my talent rather than wasting my time playing ball like more healthy children would have done.” He survived the disease, which at that time was almost always fatal, but it left its traces: it left him with a slight hunchback and his stature remained limited at 1,5 m (4’11”). This hardship did not bring any bitterness however: all sources quote him as having a most enjoyable character, “a parable of integrity and survival”.

As a youngster he developed further his musical skills, continuing a family tradition of secular string-band music shared by rural and white musicians alike (4).

One day, when working as an elevator operator, he was noticed by the secretary from the “National Life and Accident Insurance Company” which had its offices in the Hitchcock building in Nashville where he worked. He was invited to entertain a formal dinner of the company, which created in October 1925 the broadcast station, WSM. The company had its customers both on the black and white market selling small policies to low-income clients. This could explain to a large extent why, when opportunity knocked on the door, the door was opened for a black entertainer on a white radio station.

Anyhow, one thing led to another and from 1926 on he was on the air in the ‘The Barn Dance” program, renamed to “Grand Ole Opry” in 1927. He would remain there not only as the first black artist, but also the most popular one, loved by the audience both black and white. Did this audience know that he was black? Charles Wolfe (5) believes that most of this audience did not, because the radio management purposely not revealed he was a ‘colored man’, fearing that this would deter the listeners. But this proved a very wrong fear. Deford went touring “all over the south” with a band of white musicians (amongst them the country star Uncle Dave Macon, also known as the “The Dixie Drewdrop”, and labelled by some as the ‘grandfather’ of country music). Everywhere the band met with success and Deford Bailey was the star of the show.

Making music unites people, across the barriers of race, but outside of it the harsh laws of Jim Crow were inexorable. Deford Bailey, the star of the show, could not sleep and eat at the same place as the white band members did. He had to sleep either in the car, or in special accommodations in the black section of the places where they performed. He had to eat in the kitchen of the restaurants or have a quick lunch in the band’s car. These circumstances remind me of what happened to Sister Rosetta Tharpe when she was touring in the south: she performed in a separate show for blacks and whites, and at one occasion a lynching mob had thrown a black boy in the lounge of the hotel where she stayed. Louis Armstrong, when on tour with his bus, as famous as he was, couldn’t go to the toilets of the motels along the road but had to do a pee in nature.

The astonishing musical skills of Deford Bailey did not go unnoticed for the recording companies either. He had a first session in April 1927 in New York for Columbia, but the two songs remained unissued. Vocalion (Brunswick) issued 8 sides from recording sessions later that same month also in New York. Victor published 3 songs on different labels (Victor, Bluebird and RCA). As said before, his seminal ‘John Henry’ was released separately in both the ‘race’ and ‘hillbilly’ series.

Deford’s radio (and music) career stopped when he was fired in 1941 at the Grand Ole Opry. There is debate on what really conducted to his departure, and C. Wolfe calls it “essentially a mystery and one of the great tragedies in American music” (5). It did not make him however a bitter man, as many sources confirm. He gained a living renting rooms and managing his shoeshine shop. Before his death on July 2nd 1982 in Nashville, he rarely performed in public. His last public appearance was in April that same year for a homecoming show at the Grand Ole Opry.

For those who want a quick acquaintance with Deford Bailey’s music, we are lucky to have some footage available on Youtube, and I would vividly recommend sitting down quietly to watch it. One immediately understands that both his brilliant mastery of the harmonica as his lovable appearance made him a very popular artist across all racial and stylistic barriers.

For those who want a quick acquaintance with Deford Bailey’s music, we are lucky to have some footage available on Youtube, and I would vividly recommend sitting down quietly to watch it. One immediately understands that both his brilliant mastery of the harmonica as his lovable appearance made him a very popular artist across all racial and stylistic barriers.

His figure is emblematic for the nonsense that leads to the segregation of sound as K.H. Miller has so effectively described (6). But perhaps, this is at the same time the reason why Deford Bailey is on the edge of becoming only a footnote in the history of music, whilst he deserves to be more than a solid chapter. He cannot be pigeonholed. Certainly, his repertoire his not enormous and his reluctance (refusal?) to compose new tunes has been named as one of the excuses for the Grand Ole Opry to dismiss him in 1941. But his musical skills are extraordinary. His figure should also be a permanent reminder and warning that when studying the music history one must always look beyond the social filters that emerged through time. It is essential that we try to look at it in an unbiased way, taking a firm distance from all artificial categories that have been put in place or have arisen for all kind of reasons.

David Harrison (7) justly observes the high degree of integration of music in the rural south. “Making music is a circumstance under which people of both races could mix without raising very many eyebrows. Even those intolerant of integration could overlook this behaviour by musicians”. The Jim Crow laws however made such integration intolerable on the formal level of the musical scene that artificially links race and music styles. Blues was for black performers; hillbilly was for white performers. Jazz gained respectability only because some white artists had assimilated it in an early stage of its development. On the field, there was too a large extent a ‘common’ repertoire of tunes and songs which could not be immediately defined according to their racial origin. Such a ‘melting pot’ was however very inconvenient in the marketing strategies of the companies that tried to sell their product to a particular (racially and socially defined) public.

As no other Deford Bailey, who called his own music “black hillbilly”, illustrates what music in the South had in common.

When writing this I’m instinctively thinking about what I read about Jaybird Coleman (Burl C. Coleman), another one of the seminal black, harmonica artists in the same generation as Deford Bailey. It is said that at some time, at the end of the 20s, his public performances were managed by a local division of the Ku Klux Klan (8). True? Could be! After all, it would be an illustration of the cold reality that despite all the racial mixture of music “in the streets”, the social structure was highly segregated. Just as the plantation owners had their slaves perform music for them, so is it not unrealistic to state that the Ku Klux Klan would manage the performances of a black artist. This only confirmed the white supremacy and the basic conviction of the KKK that black people could not, and idealistically should never be allowed to take care of their own business…As Malcolm X put forth: “I’ve never seen a sincere white man, not when it comes to helping black people. Usually things like this are done by white people to benefit themselves. The white man’s primary interest is not to elevate the thinking of black people, or to waken black people, or white people either. The white man is interested in the black man only to the extent that the black man is of use to him. The white man’s interest is to make money, to exploit.”

_________________________________

P.S., date : 28/06/2011

Since I wrote this post, I have found two other interesting photos which have been the subject of some discussion on ‘who is who’ on http://blindman.15.forumer.com/index.php, a major forum for blues experts.

Gayle Dean Wardlow has identified some of the people of the first photo :

“That’s ROY ACUFF in front with the cake and on the back row second from left is JIMMY RIDDLE, harmonica player for Acuff with Brother Ozwald (Pete Kirby) and Charlie Collins, Roy’s guitar player in the photo.

The others in your photo are Herman Crook of the Crook Brothers, Alcyone Bate Beasley of the Possum Hunters, and Sam McGee. This is one great photo…only missing Uncle Dave Macon”

(Backstage at the Opry celebrating DeFord’s 75th birthday, photo taken by Alan Mayor)

The second photo : DeFord Bailey celebrated his 75th birthday on December 14, 1974 at the new Opry House. Here he is shown with Roy Acuff, Alcyone Bate Beasley, Herman Crook and Sam McGee. Photograph was also taken by Alan Mayor.

__________________________

(1) L. Hoffman, The Blues Harps, Parts One and Two (1991)

(2) D.C. Morton, DeFord Bailey, A black star in the Early Country Music, University of Tennessee Press; 1st edition (February 1, 1993)

(3) an overview of his life course is for instance to be found here : http://defordbailey.info/biography

(4) quoted on http://countrymusichalloffame.org.

(5) quoted on http://www.pbs.org/deford/biography

(6) Karl H. Miller, Segregating Sound : Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow.

(7) D. Harrison, Blues : A photographic Documentary, Gramercy, 1997(quoted in http://www.angelfire.com/sc/bluesthesis/musician.html)

(8) www.blues-harp.net & S.C. Tracy, 1999