When we think about music, we think in the first place about entertainment. We mostly see music as serving a pleasure need. Music can also express pain, or can sooth, as when the mother sings a lullaby for her baby. Music is an intrinsic part of our daily lives; it can range from a simple basic expression to a more complex transmission of words and sounds. It has even been found that music may have a positive impact on the functioning of the brain. Alzheimer patients have been shown to have a detailed recollection of the songs of their youth, whilst they have no recollection at all of other past events. Music helps them to bring back memories and emotions of what they experienced in their life.

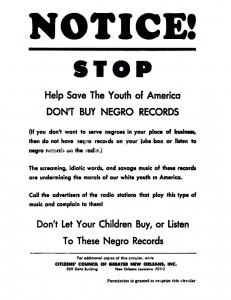

Music goes however far beyond the individual, emotional level. Music is linked to the beliefs and practices of our culture and can be seen as a form of communication, as a meaningful, structured set of signs (sounds, words) that convey a message, be it from one individual to another or to a social group. It functions at the same time as a way by which a group can express its identity or transmits signs to others groups how it feels about social facts or circumstances. The love of a particular musical style can be a form of anticipating socialisation. It can function as a plea for obtaining favourable actions coming from society or from nature. Social groups which have control in society can prevent other groups to bring forth certain musical forms because they are seen as threatening to the social structure. Music is thus next to an individual set of symbols also an important social medium. Music is in other words socially never neutral, but it is embedded in a particular social configuration from and to which it lends its meaning and significance (see also the Cantometrics study by A. Lomax).

When we conceive music in this way, we also understand that music is nor politically, neither economically neutral. Politics and economics deal with social relations and exchanges, and thus with balances of power and ways that social structures are maintained or changed. Throughout the different posts in my blog, I always want to keep in mind that blues is more than the moaning’ of an individual crying about the pain in the wake of a woman who has left or cheated him. Blues offers a unique way through which we can read the economic, political and social history of a nation and its population, segregated as it was and in many ways still is. It tells us so much about the power balance between social classes and ethnic groups since the arrival of the first slaves on the northern American continent in the 17th Century up till now.

Recently, I read an article by Norman Kelley on the Political Economy of Black Music (“Rhythm Nation : The Political Economy of Black Music”, 1999, Rap Coalition, Inc.) and was particularly seized by the similarities between the actualities in the present black music industry and what happened upon the arrival of the slaves. As a member of the white population, the further I read the article, the more I felt ashamed of the way that the rich black music has been dealt with historically and today. It made me realise once more and in this case, in a painful way, that music is not only about individual emotion, but that it is an instrument in the competition over social power and that the beauty of black music has been abused to maintain an unjust power balance over decades. It is my point in what follows that:

(a) black music in America has since more than 2 centuries been the object of expropriation by the white population,

(b) there has not existed a significant black political or economic group that has offered a meaningful counterweight for this expropriation of black music by the white, dominant group;

(c) when black musicians were to become popular to a white audience, they only did so because certain concessions they made to their musical roots.

Kelley deals with the social position of rap music and how it is under the corporate control of whites, and is mostly purchased by the white youngsters. Blacks react to their environment in a particular way, which is then taken up as a style by the white population. The record companies (white owned) push the music to the white markets. Black culture, in his words, becomes just another commodity to purchase. He confirms that there has really never existed an economic, political and social support from the black intelligentsia and emancipation movement that does justice to the historical role of black music in the American culture (1). There have been examples of black entrepreneurs and emancipation activists who have tried to gain control over the black music market and to promote it in its true value, but they have failed. Motown was sold in 1988 to MCA; the Black Swan Label (see my earlier post) had to give way to Paramount. I have highlighted in my article on the Black Swan Label that part of the reason why it did not work out with this label was due to the ambivalent attitude of Harry Pace, its leader. He wanted emancipation for the black population but failed to get a connection with its true, rich working class culture : his ideas for social uplifting were more inspired by the white culture than by what lived on the streets and in the shacks and in the juke joints. As Kelley formulates it, especially with respect to the actual black intelligentsia, but which is also applicable to Harry Pace : “Jazz and blues were urban and rural expression of working class blacks, but the black intelligentsia, trained in the aesthetics of the dominant society and unable to produce a cultural philosophy its own, neglected a very vital music in hopes of it becoming something else.” Nothing much has changed between the era of the Black Swan Label and the present black musical scene. In his article: “A Real Blues Artist and Inventor”, Robert Willis, cousin of Chuck Willis, tells in words that leave no doubt about their meaning about what it means for black blues musicians to be confronted with the dominance of white musicians on the musical stage today, and how after all the latter seem “only to be interested in what sort of money they can make by using the name Blues.” (2)

Is there indeed not a continuing story of the white population expropriating black cultural forms for its own lucrative goals and trying to get it into the mainstream (the popular uniform music that sells well), but adapted in a form that didn’t conflict with the social order that it controlled? The black music has always been sort of “whitened” to prepare it for the mainstream market dominated by the white segment with the purchasing power (I won’t mention the name of Michael Jackson who even “whitened” his face).

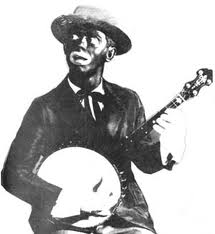

Already in the antebellum period, plantation owners would use some slaves not (only) for field work or household services, but would also let them perform as musicians (Marshall Wyatt). The leading white class controlled the way that some blacks could perform their music as entertainment, not only for themselves; they were also encouraged to play for the dancing of their fellow slaves as well. Their music integrated African and European influences. Their instrumentation combined the European violin and the African banjo (banja), and the performance included polkas, marches, jigs and reels of European origin. The percussion and drums, so typical for the African music, were banned because of their potential for social upheaval. Drums and fifes could only be found, played by blacks as well as by whites, in the appropriate context of the colonial military organisations where marches were supposed to contribute to the patriotic feelings and military energy.

In later decades and during the Reconstruction Period, the minstrelsy was the way that the white population dealt with the black music. One can see minstrelsy and black faces as a covert way in which the whites expressed their latent recognition for the richness of the black musical culture. On the outside however, it came down to a comedian presentation of ridiculous and denigrating black stereotypes which was based on black music, but never represented the true spirit of it. The strength of the minstrelsy shows was such that even when black artists joined the shows they put black cork paint on their faces, just as the whites did ! It was the way that the blacks were accepted on stage. The popularity of the shows also within the black population testified of the efficiency by which the white population had succeed in having their control over the existing social order internalised with the people it oppressed (see also Scott Wilkinson – A Reassessment of the blues revival in America, 1951-1970, 1998, quoting Eric Lott : “The phenomenon of minstrelsy itself was an admission of fascination with blacks and black culture”. However, it did not represent the African-American culture at the time since the singing, dancing, and comedy performed at minstrel shows were, in reality, unique demonstrations of Americana in all of its multicultural glory” (pp. 11-12).

Once the African-Americans were freed as slave, the Reconstruction Period witnessed the popularity of the jubilee companies, groups of a Capella black singers who mostly had their social roots in the middle-class and black colleges. Some of them did some intensive touring, bringing them even on the international scene. The most famous are the Fisk Jubilee Singers that considerable contributed to funds raising for the Fisk University. Their repertoire was mainly spirituals, but also songs by the ‘Father of American Music’, Stephen Foster. Even though the aim of the jubilee groups was to offer a counterweight for the negative stereotypes that were promoted by the minstrelsy, they failed to build upon the culture that had grown on the fields and in the shacks. Their popularity was derived from a firm grounding of their style in the vocal harmonies of the European culture: university Jubilee groups presented folk material in a Western classical idiom by relying on cultivated voices and formal performance practices, thus bridging the gap between “art” and “folk” realms. There was no indication of the promotion of the richness of the musical culture that had grown on the plantations.

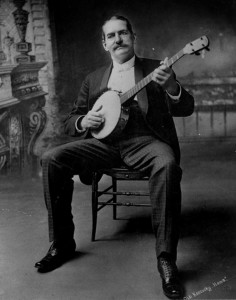

The same can be said of Polk Miller, who is the first white person who aimed at reviving the older black music forms in an authentic manner. As the son of a plantation owner, he learned how to play the banjo from his father’s slaves. His career started out as a pharmacist, but turned to music in 1892, billing himself (without a black face !) as the “The Old Virginia Plantation Negro” . He toured with “The Old South Quartette”, a changing group of black vocalists. Their repertoire was black and white spirituals, coon songs, confederate war anthems (a capella or with banjo accompaniment). (Scott Wilkinson, 1998). His popularity however didn’t go without concessions to the constraints imposed upon him by the white population: it is said that he stopped from performing because he feared for the safety of his black musicians, who were sometimes even forced to perform behind a curtain, leaving Miller alone visible on stage.

In total respect for the achievements of Polk Miller, one cannot ignore the nostalgic perfume that surrounds his work and music. ” The show aimed at pure nostalgia, as seen in a 1910 brochure emphasizing that the Old South Quartette were “genuine” Negroes: “Their singing is not the kind that has been heard by the students from ‘colored universities,’ who dress in pigeon-tailed coats, patent leather shoes, white shirt fronds, and who are advertised to sing plantation melodies but do not. They do not try to let you see how nearly a Negro can act the white man while parading in a dark skin, but they dress, act, and sing like the real Southern darkey in his ‘workin’’ clothes. As to their voices, they are the sweet, though uncultivated, result of nature, producing a harmony unequalled by the professionals, and because it is natural, goes straight to the hearts of the people. To the old Southerner, it will be ‘Sounds from the old home of long ago’. . . . To hear them is to live again your boyhood days down on the farm.” (program brochure quoted on http://jasobrecht.com/polk-miller-and-his-old-south-quartette-1910/) . The premise of his show was that he was the judge of the real African American Culture. It is hard to put the suspicion aside that pure nostalgia about the old, ante-bellum social order, was not far away.

The white domination of the black culture would in the later decades, with the advent of the technology (radio and recordings), only become more manifest, less subtle and more brutal. It would take us too far in the short span of this article to go into much detail on how the ownership of this technology by the white classes impacted blues (and black music in general). I need to remain schematic and quote only some of the more obvious manifestations of it. The essence however is that the African American population more than ever began to lose control of their music with the growing complexity of the technological environment of both production and distribution.

It has been documented extensively how white record companies, whose executives did not have the faintest idea about the black music, finally started to promote ‘race records’ because and only because they realised that there was a market for it. By this very ‘industrialisation’ of the music business which put radio and recording as key technologies on the foreground, the artist started to lose grip on his repertoire, on his ‘product’. In analogy of the separation of labour from the household place in the process of industrialisation, where plants and capital hired labour to produce commodities, so did the artist became in a way ‘segregated’ from his product. His “production” would be determined by what the recording industry executive would see as the demands that lived on the market. Whilst for instance string quartets were enormously popular in the beginning of the 20th century, the recording business did not want to take a gamble on the fiddle and the banjo. The first years of the 20s vaudeville, female, vocal blues proved to be very popular, and only from the midst of the 20s the individual, black country guitarist was seen as a product that could be commercialized. The Great Migration had led to a huge displacement of African Americans to the Northern, industrial cities and just as the record companies at the end of the 1910s tried to connect the European ethnic groups to their home country with nostalgic ethnic music, they now appealed to the homesick feelings of the southern immigrants in the ghettos of Chicago and other northern cities. Was it a coincidence that Muddy Waters first scored a real hit with ‘I feel like going home’?

The popular string bands were of much less interest to the recording companies even if some of them succeeded in building a popular basis. They reacted by dropping also their classical fiddle and banjo, changing their repertoire, or – cosmetically – by quoting the magic word ‘blues’ in the title of their songs, even if the songs were no blues.

The loss of control over its repertoire was also very obvious amongst the blues musician. He was literally taken a few hundred miles away to the studios and plants of the companies up North to have his work waxed, unless the company was financially solid enough to bring the recording machines down locally at a nearby hotel. Of course, obviously, this was only worthwhile if he had at least 2 numbers that could be considered as commercially viable; if he did not have at least two songs, well then he was asked to improvise one on the spot. Whilst in the juke joint or during the fried fish picnic, blues was played at full extent, in intimate interaction with the audience, improvising and extending the song in length at pleasure, in the studio the red light without forgiveness ended the song after a maximum of 3 minutes. The song was put into the straight jacket of the technological limitations of the 78record. Record companies also saw to it that when they brought the musician to the studio there was enough material recorded to allow for successive distribution and publication. They alone decided on what was issued, without the artist having any saying in this.

It has been written enough that the repertoire of many an artists was impoverished and narrowed to mere blues whilst their entertainment capacities reached much further. I’m not going into detail either about the shameless way that the copyrights were handled.

The greenback, more than ever, determined the way that blues was brought to the audience. It is my thesis that only in a very short span of time, in fact during the years that blues emerged as a musical form sui generis, the artist had full control on his output. Before radio and recording business took the lead, there was no physical or technological separation between the producer and the consumer, between the singer and his audience. Audience and singer were one : the blues musician expressed the emotion of the group. Music was an essential element of the social fabric of daily life. It was, according to me, this very freedom that the African American had during a short span at the end of the 19th, and the beginning of the 20th century, that allowed him to develop this great form of art, that was in his very essence a way to digest the cruelties of the past and to express the hope for a better future. Pain, hope and joy all joined together.

It were not the jubilee groups, nor Polk Miller and his quartet that would be at the cradle of this musical form that would later conquer the world, though this conquest would come at a price, since it was not the African American population itself that would bring it into mainstream, but the white segment of the American population.

Much as the white ethno-musicologists have done for the exploration and the promotion of the African American music, one needs to stay critical with respect to the way that they have approached it. Surely, the nature of their impact was not on the same level as the distortion brought about by the interest by the record companies, but even when considering the achievements of Alan Lomax a.o. it is important to interpret it without prejudice. In some sense, these scholars reacted in just the opposite way of record companies forcing the attention on the repertoire of the musician which was deliberately left outside of the scope of the recording companies. One extreme was set against another. What is important to note however, again, is that the interest in the black folk music was mainly carried by liberal, white young men inspired by emancipation ideals or even just by the interest of collecting old records. One needs to be on guard and try to figure out to which extent their own definition of what true African American folk is did not contaminate what they registered and highlighted.

Another clear illustration of the absence of a black political and economic support for its own cultural working class product manifested itself in the role that was played by the folk revival. I won’t go here into the blues revival as it developed at the end of the 50s and during the 60s. This is largely out of scope of my interest field. Even the early white interest in the black music during the late 30s and early 40s serves enough as illustration. It was the active interest by liberal, white folk enthusiasts that brought some black performers on the foreground. To start with Leadbelly whom Francis Davis called the first black country performer to appeal to mostly a white audience, and not a black audience. He paved the way for many other ‘folk’ singers. Following his example, “other black musicians who had played blues among other styles of music or had promoted themselves as blues singers followed Leadbelly’s example and relocated to New York City during the 1930s and 1940s in order to play for the white leftist coffeehouse audience” (Scott Wilkinson, 1998). Leadbelly would be followed by for instance Josh White, who would even have a close and long relationship with Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. Josh White Jr. can even call the Roosevelt’s his godparents.

It was thus whites who brought White as a prolific race recording artists to the White House. But was he still singing the true working class blues?

It is now up to you to start discussing.

Footnotes :

(1) I will deal with W.C. Handy and W.E.B. Dubois in later posts.

(2) Thanks to Rene Trossman for pointing me out on this article.

Thanks to my wife, Chris, for a critical reading of a draft version of this text.