In my previous post I stated that blues helped to save the record industry. I should be more precise: women blues vocalist helped to save the record industry. In its kick off phase blues was mainly a woman’s business.

Most of the literature focuses on the role that classic blues has played in obtaining public recognition, but a lot less attention is paid to the composition of both the live audience and record buying public of the male country blues songs that followed the female classic blues of the twenties. Who was the public most eager to see and hear the early stars as Charley Patton & Son House? Exactly: it was women. Some of those early male blues stars were fabulous entertainers who were especially beloved by women (and they, from their side, loved women not to a lesser degree). Their sexually inspired songs had no difficulty to appeal to the female audience. Who bought their records? Yes, precisely, it was in the first place the women, who could bring the voices of their beloved artists come to live on their Victrola’s at home. Men were more interested in gambling and drinking in the juke joints, during the week ends, after a back breaking week of hard labor on the cotton fields or in the early factories.

It would be interesting to find some material on this aspect of the women’s role in the prewar blues, but up till now I didn’t find much.

As said, most of the attention goes to the central role that was played by women in the emergence of blues as a popular genre. There is quite some debate going on whether this early, classic blues can be considered as real blues. It certainly isn’t compliant with the image of the wandering, male black with his guitar (phallus symbol?) in his hands, wailing and howling’. Formally, the early female blues respects the technical, musical definitions of blues, and we can only exclude them from the blues history if we continue to consider it as a mere form of folk, male country blues, later turned into electrified blues in the urban environments of Detroit, Memphis, Chicago and the like. It is my opinion that the female blues which got on stage already before WW I is clearly a part of the general blues history. It had its roots in the folk & ragtime, and it is clearly situated in the wave of popularity that followed the first publications of blues as sheet music by a.o. W.C. Handy, Hart Wand and Arthur Seals (see here)

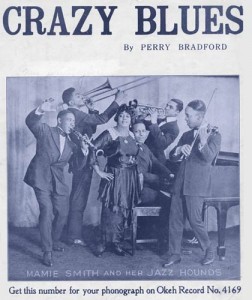

The story of the classic blues usually starts with the commercial success of Mamie Smith’s ‘Crazy Blues’ in 1920. Both coincidence and continued efforts of Perry Bradford, an African composer, songwriter and vaudeville musician with a fine nose for what the public wanted, are at the basis of Mamie Smith’s success (the record sold more than a million copies in the first year). She made it to the horn of the recorder in the studio only by pure accident because the artist who was invited (Sophie Tucker) didn’t show up. Her first recording was not blues; it was only afterwards that Okeh records called her back to register ‘Crazy Blues’ on wax.

This commercial success didn’t come out of the blue; it didn’t come falling from the sky. Ever since the publication of “Memphis blues” & “St Louis Blues”, there was a rush into the blues, even if not all of the songs were formally to be seen as blues, but only used the terminology as a marketing instrument. When record companies smelled that there was a market to be exploited within the black population, they immediately started looking for other talent to wax at the same level of Mamie Smith’s. And this talent was really not hard to find, it was there at their very disposal; all they had to do was to get some highly professional female entertainers in the studio. Ma Rainey for instance was already on stage in black minstrel shows for several years and had trained Bessie Smith, whose first record (Downhearted blues, written by Alberta Hunter) helped Columbia to rescue from financial meltdown : the record sold more than 770.000 copies ! Even by today’s standards, this is huge.

The list of female blues vocalist that became popular is long: Ida Cox, Sippie Wallace, Mattie Delaney, Berta Chippie Hill, Lizzie Miles, Bessie Jackson, Mary Johnson, Trixie Smith, Maggie Jones and I forget others.

This success had clear links with black minstrelsy which served as a feeding ground for the artists. It is also linked with the spread of black entertainment in the twenties which was a period of economic booming. It is moreover connected to the emergence and spread of the cabaret in the Northern cities. Finally, the popularity of female blues singers cannot be understood without referring to the broader emancipation of women during the twenties. This period of profound technological and social change also saw the emergence of the free spirit of women who had obtained the right to vote after WW I. There was even a specific word for the new emancipated woman who wear shorter skirts, showed her naked arms, wore short hair and danced The Charleston : a flapper.

Let there however be no misunderstanding: the women liberalization movement was a white, middle class phenomenon. Segregation continued to rule the racial waves. When record companies issued black music, they did so through a specific production and distribution channel targeted at the black (younger) population. Race records were often the product of subdivisions of larger record companies.

Anyhow, those female pioneers of the blues were the first to sing the blues as professionals, also in the sense that they made their earning from it, in contrast to the black, male blues singer for whom manual labor and blues singing coexisted on their CV. Some of the women remained in the South and joined travelling vaudeville shows which brought broad entertainment also including dancing and theatre. Other women followed the big migration to the North where the industry was booming and where there was plenty of work in the factories. They were often backed by a (jazz) band, which served at the same time as an expression of a communal feeling in a city environment that was completely new to them. Their style developed also into a more fancy style, adapted to the requirements of the city public.

The Great Depression put a final stop to the first classic blues. Many left on retirement; others pursued their career, but only years later. Meanwhile, the male black musician had been discovered by the record companies, but only thanks to the women that had paved the way for blues as part of the mainstream music.