According to Angela Davis, political activist, writer and academic (1), the archetypal blues singer was a solitary wandering man whose principal theme was the sexual relationship to which all other themes sooner or later reverted (Giles Oakley (2)).

Whilst going through the material in preparation of a coming article I plan on boogie woogie I was indeed again confronted with one of the significant aspects of the early blues: the geographical mobility of its musicians. The train was a notable vehicle, though not the only one. Anything that would bring the musician from one place to another to perform was good. This dimension may seem obvious in our present day society, but it was not the case in the immediate post Civil War period. Evidently, during the slavery period, the African Americans were anchored to the soil by the rigid rules of the plantation system which granted them the same mobility as the plantation owner’s cattle. This changed with the abolition of slavery, though practice was slightly different from theory. Quickly, the shackles of the share-cropping and tenancy replaced the property rights of the plantation owner. Of course, geographical mobility was not excluded, but the concept of freedmen leads erroneously to believe that the African American could move from one place to another without any practical restrictions. Economic necessities and dependencies hampered his mobility capacity.

For some however, who choose to gain their living by making music instead of working in the economic structure owned by the dominant white, the roads lay open. The itinerant musician traded in the uncertainty of the crop output and the pay that it might bring for the uncertainties of the number of nickels and dimes which he would get from his next audience. On the one hand, this social ‘escape’ put him at the outside border of his social group; at the other hand, it granted him a certain status as an entertainer, an artist, and, by the fact of his mobility, he also was the carrier of news from one region to another.

The absence of the legal proscription on free travel, i.e. the possibility for rambling can be considered as a major characteristic of the inheritance of the abolition of slavery. “The very process of travelling must have generated a feeling of exhilaration and freedom in individuals whose ancestors had been chained for centuries to geographical sites dictated by slave masters.” (1)

As stated above, the train was a major technical means of transportation. If the train conductor was kind enough the musician could keep him company in the cabin of the locomotive, otherwise he would travel around as a stowaway. And the possibilities for travelling by train were largely at hand and expanding in the second half of the 19th century. The train connected otherwise lost hamlets to regional centres from which cities came within reach. Train companies were also big employers in their ever growing expansionism, which – the past repeated itself – hired mostly (but not exclusively) black labourers who had to work in the most inhumane circumstances. It is said that some train companies even ‘owned’ (part of) their black working personnel.

Though the train theme is a major one in folk music, and especially in the Southern American folk music, it plays an utmost import role in the blues. The train was a symbol of freedom, it was the icon of the getaway out of social misery that would bring the impoverished black to the urban centres where more money could be made and where the cruel Jim Crow was less present. The number of songs that have the train as a central theme is almost countless, and would require a study of its own. In my coming article on boogie woogie I will mention only one in particular, “The Fives”, which occupies a very special position in the evolution of this music style. It is often said that boogie woogie has sought its main inspiration in the sounds of the train as a kind of onomatopea, but this is open for debate. In any case, the train, as a symbol of the way out to freedom was present in almost all folkloric music styles.

Peetie Wheatstraw sang : “When a man gets the blues, he flags a freight train and rides”

Angela Davis asserts that the introduction of the legal freedom to travel was one of the major social shifts that came with the suppression of the slavery system. It was one of those freedoms which the ex-slaves had to learn to handle. But was it the most important one? Unlikely. As slaves, the lives of the African Americans had been organised from birth until death by the plantation owner. Whatever they brought along from their African cultural background, their norms for social interaction were forced to either go underground or to disappear all together in their new environment. So, with the abolition of slavery in 1865 came also the challenge for the African Americans to build up an entirely new way of living. The segregation installed by the white class forced them even more to this social reconstruction task.

A central element of this social tissue that they were expected to restore was the family concept, the relation between men and women, the development of rules regarding the division of labour along gender lines. It would be interesting to investigate more into detail the way in which their previous normative system helped to shape their new social guidelines in this respect. In any case, the theme of the gender relation was a prominent element in their (new) cultural space which were the blues. This should not surprise after decades during which the mating between men and women was subjected to the arbitrariness of the plantation owner, and during which women were regarded upon by their owner as just another work force element that on top was able to breed new work force (whoever was to ‘create’ this new labour force) (*).

The approach of sexuality within the post bellum African American population was distinct in two ways: it didn’t follow the romanticized image of the two love birds who finally married, and it was far from being puritan. The patriarchal model adhered by the white cultural mainstream depicting the woman/wife/mother responsible for the household and the man as the provider, breadwinner, was difficult to implement given the socio-economic pressure for black women to contribute to the household income.

The blues image of love was far off from the non-sexual image of the heterosexual love relationship in the mainstream culture. Extramarital relations, domestic violence, the shortness of love relations, homo-sexual relations were dealt with in a more or less explicit way, using sometimes a very colourful vocabulary. The interaction between the genders in all its realism was without any doubt one of the most important aspects of everyday life which constituted a central theme of blues. The sexual act itself was not ignored. Robert Johnson sung: “Squeeze my lemon until the juice runs down my leg”. Bo Carter made the ‘double entendre’ in a way is hallmark.

One could of course debate whether the absence of the romanticized love theme is linked per se to the racial division or whether it is more a class related matter. It seems a bit odd to suppose that when children were forced to harsh labour from a young age, black or white, being confronted with working and living conditions which made everyday a struggle for live, that there was still some room left to dream of romantic love relations full of white doves flapping around.

But this race-class discussion is another topic.

Fact is that the sexual relation (hetero/homo) was a prominent item in the repertoire of the wandering, itinerant blues musician, who himself was most of the times a star actor in multiple relationships that came along in the wake of his performances in the juke joints and barrel houses.

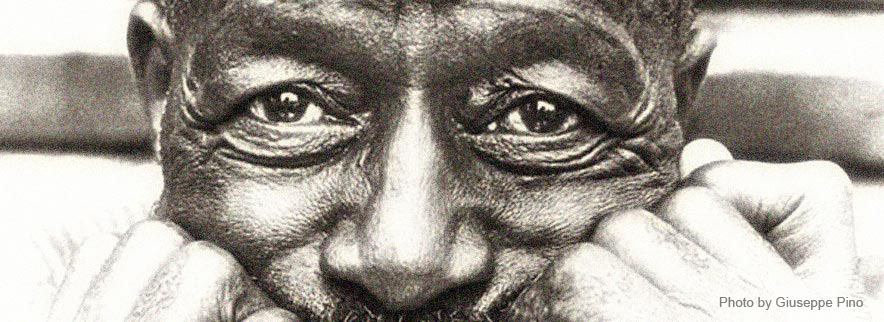

This did not really change when the country blues was transformed to the urban blues. Muddy “Mannish boy” Waters got his “mojo” working thereby highlighting his high libido, and he had his ‘Two trains running’. Howlin’ Wolf (one of my blues heroes) made the lightning of the train’s smokestack into a blues classic. On the origin of ‘Smokestack Lighting’ he said: “We used to sit out in the country and see the trains go by, watch the sparks come out of the smokestack. That was smokestack lightning” (3).

I cannot put the image out of my mind of a couple having sex in the glow of the lightning of the smokestack of the trains rolling by in the background….the blues summarized in a quasi pastoral scene.

_____________________________________________________________

(1) Angela Davis, Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday, Vintage Books, 1999

(2) Giles Oakley, The Devil’s music : a history of the blues, 1997

(2) Rolling Stone, 2004.

(*) The marriage as an institution did not exist during slavery times. A man and a woman could ‘contract’ a relation, but this would only last as long as the plantation owner did not interrupt it by dividing the group of slaves, or selling them. The most common vows at slaves’ weddings were “until death or distance do you part.”

[…] Continue Article Here… http://www.myblues.eu/blog/?p=1163 […]